Our columnist reveals the many ways she’s benefited from her love of reading—and shares the latest book to capture her attention.

I’ve been blessed with a love of reading all my life. In my early years, when a passion for horses couldn’t be assuaged with the real thing, books had to serve instead. Whether it was Black Beauty or an issue of Western Horseman magazine, my nose was always pressed into something “horsey.”

A knowledge base began back then, and I continued to add to it later. As a young rider, a California competition called Horsemastership opened my eyes to the Cavalry Manual, the AHSA Rule Book and other resources. Since then I’ve read anything else I could lay my hands on to learn more about this animal that never fails to fascinate me.

Fortunately, neither my passion for horses nor that for reading abated as I got older. While I no longer own or work directly with horses (except those of my clinic participants) I feel like my knowledge of them and of the sport continues to grow, in no small part from reading.

“I feel like my knowledge of horses and of the sport continues to grow, in no small part from reading,” says Linda Allen. Photo by Mollie Bailey

As today’s world revolves so closely around the Internet and social sites in particular it’s likely many of the current generation will never know either the pleasure that comes from reading or the insight that can be obtained that way. The Internet is great for researching facts (though it often produces fiction instead!), but its stark and condensed delivery just doesn’t set one’s mind and imagination in gear the way a book can.

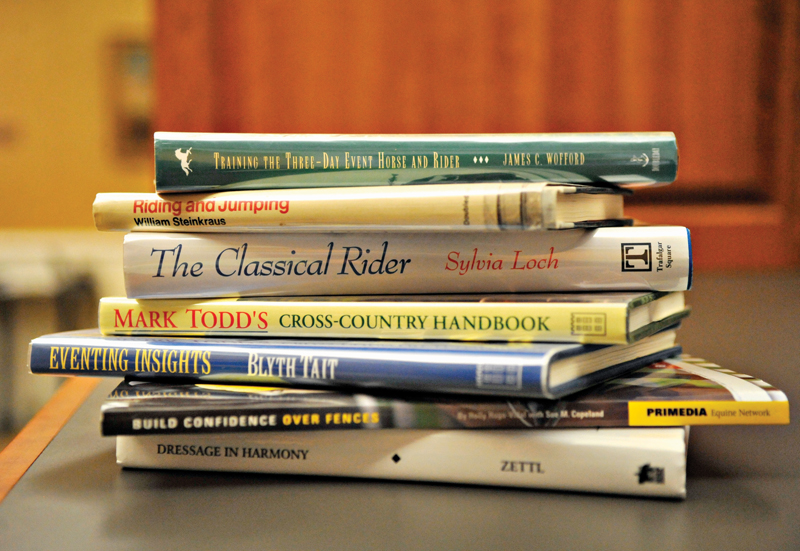

Like everyone I know my schedule is overfull, and e-mail takes ever more time. Yet one way or another I manage to get through my favorite two magazines: The Chronicle of the Horse and Practical Horseman. I skim most everything and find that often columns and articles that stir my interest are from horsemen in other disciplines. So often there is much to take from their writing that applies so directly to my own disciplines. I never miss Jim Wofford’s columns and books. While eventing is his discipline, his insight into the mind of both rider and horse, along with his ability to use humor to make his point, always leaves me contemplating how much the various disciplines have in common.

Denny Emerson is another I look forward to reading. He brings a sense of history, timeliness, and the breadth of his lifetime of equestrian pursuits to every column. There’s always a little more for the brain to ponder after finishing one of Denny’s essays.

I wonder how many in the jumper world read Charlotte Bredahl-Baker’s recent Chronicle column, “Riders Need to Make Their Own Opportunities.” Since Charlotte writes about dressage my guess is that few outside that discipline read it. Yet her comments regarding what it takes to become an “overnight sensation” are right on the mark no matter which discipline an upcoming rider might be pinning her hopes and prayers on. Charlotte gave the background on the lesser-known members of last year’s Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games dressage team, outlining all the years of just plain hard work they logged before their breaks came. She points out so clearly how the riders with an old-fashioned work ethic, together with patience and persistence, are the ones most likely to make it in this sport. This particular article should be read by anyone declaring a desire to “go to the top” or “ride in the Olympics.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The Talent Code

Besides periodicals I fit in quite a few books as well. The latest one to transfix me was The Talent Code by Daniel Coyle. It’s interesting sometimes how one comes to hear about a particular book. I opened an e-mail from Dr. Doug Novick, a veterinarian in California, who happens to have a really neat mare he’s brought along himself to the high amateur-owners and smaller grand prix classes. I met him when he started attending some clinics with me. Doug’s e-mail was a newsletter he sends out, and this edition was titled “How to Improve Your Riding.” In the article he discussed Coyle’s book and outlined the concepts it brings forth about the differences between “talent” and “skill.” This topic has intrigued me ever since being fascinated by Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, about success.

A stop at an airport bookstore didn’t produce The Talent Code so I was thrilled when my Kindle could download it for me that very day (ain’t technology great!). I admit to speed reading through some of the neuroscience parts, but the premise, the science behind it, and the examples discussed all rang so true according to my own experience as a rider, a trainer and a teacher. I couldn’t wait to get home from work to pick it up again and admit to reading until late two nights to finish it.

The author’s initial curiosity in the subject came from reading about various “hot spots” where exceptional talent was being produced at rates far exceeding the norm for anywhere else. Whether professional baseball players from the Dominican Republic, women’s tennis stars from a tiny school in Russia, world-renowned musicians from a ramshackle facility in the Adirondacks, or multiple “American Idol” finalists from one vocal studio in Dallas, he wanted to know what it was about these places that could impart so much talent on the world.

Coyle found far more similarities than differences between the hot spots he visited. There were similar levels of “amenities” in each location (it seems that “basic” would be a generous description), similar teaching styles (intense but quiet, dedicated to details and “the basics,” absence of denigration or cheerleading), and a dedication to inspiring the quest for perfection in their students including acceptance of delayed gratification and de-emphasis on competitive drive at an early stage.

It seems it’s not a matter of discovering raw talent but instead growing talent through the acquisition of exceptional skill and desire. Except for those requiring purely physical characteristics, such as height in basketball, practically any skill can be learned if one puts enough time and energy into acquiring it. Well-developed, fast and reliable nerve pathways are what skill is all about, whether we are talking baseball, music, chess or riding a jumping course. Science has demonstrated that the nerve pathways that function best are those coated with many layers of myelin (insulation), and adding those precious coats takes lots of time (and sweat and tears). Coyle’s investigations verify the 10,000 hours of practice required for the sort of serious skill to develop that can bring world-class success—the same number cited by Gladwell in his book, Outliers.

A lot of the book is spent discussing the concept of “deep practice”—the sort that is based on concentration, training “close to the edge” and utilizing mistakes as an integral part of the learning process. Time spent in more casual practice just doesn’t cut it when it comes to laying down the myelin. There is an enlightening discussion of bad habits and why they are so hard to break. Another topic—that of subconscious imitation—was especially interesting for me having encountered it so often in the various clinics I conduct.

The All-Important Desire

ADVERTISEMENT

Along with deep practice, the second critical ingredient for making it big time is what the author calls “ignition.” This is that all-important desire to do what you’re doing that makes deep practice enjoyable instead of a drag.

Many rather vague factors influence this aspect, but two things in the book stick in my mind. The first is that too much praise (especially the kind that wasn’t earned through real effort) doesn’t ever seem to create ignition. The second was a study done that showed 7- and 8-year-olds, before their first lesson with a musical instrument, who were asked if they thought they would play it: a) this year; b) all through school; or c) all their lives. The ones who chose c) were the same ones who excelled, by an astounding margin. They progressed far faster, even with less actual time spent in practice, than those with a shorter-term commitment. It seems little is known yet about the origins of “ignition,” but my guess is that many of you felt it when you embarked on the equestrian trail.

The third factor in creating life-changing skill was the sort of coaching received. Coyle calls it Master Coaching but clearly distinguishes the sort of coaching techniques that are geared solely to winning games from those that are most likely to transform an individual into a real talent. In the section on coaching, Coyle discusses the qualities of those special teachers who impart the desire to learn in younger students—such an important piece to the puzzle. With great frequency studies show great athletes and musicians began with “average” teachers—“average” in terms of professional prominence maybe but not in terms of the basic skills and desire to improve imparted to their young students.

For individuals striving for mastery of a given skill, coaching that revolves around three key concepts will speed their development. Those concepts are: knowledge, recognition and connection. A very extensive matrix of knowledge is an absolute necessity for any master coach. Along with this knowledge must come the ability to recognize the smallest detail of what the student is doing at every moment, together with an ability to connect with each individual student to find the sweet spot for deep practice.

Being a master coach is no different from being very, very good at anything else. It’s a skill that takes lots of time and effort to achieve. It doesn’t happen overnight and isn’t a “God-given skill” imparted on someone but rather the result of their desire and the hard work that they invested in perfecting their skills.

It’s probably easy to see my fascination with this book. For those of you with a similar interest in such things I only hope I’ve whetted your interest and haven’t given away too much of “the plot” and spoiled your reading pleasure!

There’s no limit to the joys that come from reading, and one I enjoy in particular is sharing my finds with friends. In fact a good friend who I told about the book just returned the favor and emailed me a link to Daniel Coyle’s website, so excuse me while I switch screens and continue my reading. Old habits die hard—though the technology has changed a bit since my childhood!

Noted international course designer Linda Allen created the show jumping courses for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and the 1992 FEI World Cup Finals. She’s a licensed judge, technical delegate and a former international show jumper. She lives in Fillmore, Calif., and San Juan Cosalá, Jalisco, Mexico, and founded the International Jumper Futurity and the Young Jumper Championships. Allen began writing Between Rounds columns in 2001.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to read more like it, consider subscribing. “Reading Reaps Great Rewards” ran in the May 2, 2011 issue. Check out the table of contents to see what great stories are in the magazine this week.