If Neal Shapiro ever had to sit down and compose a résumé, he might have trouble fitting his myriad accomplishments onto a single page.

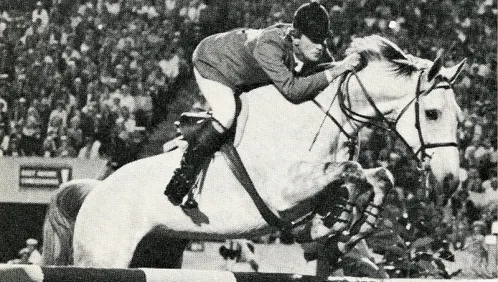

An individual bronze medalist in show jumping from the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, Shapiro was inducted into the Show Jumping Hall of Fame in 2010.

He also spent 20 years cultivating a career as a harness racing trainer. In his spare time, Shapiro is a pilot and an accomplished organist. “I change occupations about every 25 years,” Shapiro said wryly.

That might be, but one thing remains constant: Shapiro is a consummate horseman with a fascinating breadth of experience and astonishing humility.

“He’s not flashy. He’s just a solid, good person and solid, good rider,” said Kathy Kusner, who was Shapiro’s teammate on the ’72 silver-medal Olympic team.

“There wasn’t anything fancy about what he did; he was a very straightforward horseman and rider. He just went and did what he normally does, and when the dust cleared, he’d be right there on top.”

Even though he was competing at the highest echelons, Shapiro never lost his ready smile and down-to-earth approach.

“Anything that needed to be done, Neal was front and center, ready to do it, whether it was driving everyone around in a Volkswagen bus or unloading tack trunks,” said Kusner.

“He would haul trunks around with a big smile on his face. He was the easiest person to get along with.” Shapiro spent just 12 years on the international show jump-ing scene, but in that time he won the Grand Prix of Aachen (Germany) in 1966, then tied for that same title in 1971.

Along with his Olympic medals, he contributed to 12 winning Nations Cup efforts for the United States.

“I never thought I’d reach the level that I did,” Shapiro said. “I had to learn a lot by myself, but it was definitely what I wanted to be doing. It all worked out for the best, and it was a great experience.”

And after a 20-year hiatus from horse shows, Shapiro, 65, has returned. He and his wife, Elisa, run Hayfever Farm in Robbinsville, N.J., where they train and teach hunters, jumpers and equitation.

Getting Noticed As a junior rider, Shapiro was mostly self-taught, riding at his family’s small farm in Old Brookeville, N.Y., on Long Island.

“Riding was very different back then. Horse shows were very different. What I picked up was just from listening to and watching the good people and the best horsemen out there. I would copy what they were doing or experiment. I would see if I could get somewhere close and make things work,” he said. Shapiro did show in the equitation and hunter divisions, but his heart was in the jumper divisions.

“I remember both years that I qualified for the Medal Finals and Maclay Finals, I rode the same horse in those that I rode in the open jumper classes at the Garden. One year, I won a big open jumper class at Madison Square Garden on Thursday night with the mare Cameo, and she was my horse for the Medal and Maclay Finals two days later. There were no specialized horses in those days; most of the people did the equitation on their hunters,” Shapiro said.

In 1961, at the age of 15, Shapiro won the AHSA Horse of the Year title in the green jumper division aboard the talented, but difficult, Uncle Max. He and Uncle Max continued to do well, and in 1963, Jacks Or Better joined them.

By 1964, Sha-piro was doing well enough on Uncle Max and “Jacks’’ that he was invited to the selection trials for the Olympic team. But when they told him the format of the trials, he knew his horses weren’t quite cut out for it. “The first day was them observing you flatting your horse for an hour.

I said, ‘OK, that’s out.’ All Uncle Max would do was go on the end of a longe line until we got to the horse show. It wasn’t even worth getting on him for flatwork. The only time we got on him was to jump,” Shapiro said.

Jacks’ flatwork was more manageable, but he had a shuffling gait unsuited for showing off on the flat. “The second day was a dressage test, and I didn’t have any idea what to do in a dressage test. You could have told me anything and I would have believed you. The next day was gymnastics and cavaletti, and that wasn’t going to work because Uncle Max would just smash them all, and Jacks, I didn’t know how he was going to shuffle over cavaletti,” Shapiro recalled.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Then the last day was jumping a modified grand prix course, which was the only thing I knew my horses could do. I asked if I could just show up for the last day with either one of them and see how I got around,” said Shapiro.

Eventually, someone loaned Shapiro a green horse for the first three days of the trials, and he jumped Jacks on the last day. He didn’t make the team, but he impressed Chef d’Equipe Bertalan de Nemethy enough to be asked to join the fall Nations Cups team. Shapiro rode on the team at the Pennsylvania National Horse Show and the National (N.Y.) in the fall of 1964.

“For me, that was a great thrill and honor. When you’re a little kid and you go to the Garden and you see these international riders, it’s pretty impressive. To be one of them was a thrill,” said Shapiro, who was just 18 at the time.

Over His Head

After the fall circuit, Shapiro was invited to the winter training sessions at the U.S. Equestrian Team headquarters in Gladstone, N.J. He transferred to Rutgers University and moved to New Jersey for the winter.

“It was a very eye-opening experience for me because I realized that I knew nothing about horses,” he said.

“I rarely got to ride either of my horses; Bert worked Uncle Max and Jacks Or Better. When the training session was over and I went back to the horse shows, I was pretty lost. I had a hard time adjusting to riding these horses in a totally different style.” Shapiro spent the summer showing and trying to improve and was asked back to USET training for the winter of 1965.

“Uncle Max was not invited back, but Jacks Or Better was, and I did get to ride him a little bit more. I was learning, but it was still hard. I’d watch the other riders who were there training, and these were kids who had had top trainers and great horses and had won the Medal and Maclay Finals, and I felt a little bit out of place,” he said.

In the summer of 1966, Shapiro was invited to travel to Europe with the USET, and he felt even more out of his depth. “I suffered for the first couple of shows. I was struggling to get these horses around the courses. I wasn’t used to the technicality of the courses and the speed you had to go. To get Jacks Or Better to go without a standing martingale that was 18″ short and gallop around there was hard to adjust to,” he recalled.

“I remember we were out working horses one day, and Bill Steinkraus came over, and we were discussing things,” he continued. “We all discussed our horses and how things were going with them. He made a suggestion, and I tried it, and the whole world changed for me with one little adjustment. He said, ‘Shorten your stirrups two holes.’ I don’t know if that’s what really made the difference or not—maybe it’s coincidence—but everything clicked then.”

Things clicked just in time for Shapiro to beat the best riders of Europe as he and Jacks topped the prestigious Grand Prix of Aachen.

Ask And Ye Shall Receive

In the three years after his Aachen triumph, Shapiro suffered from lack of horsepower. Uncle Max had been sold, and Jacks was retired after an injury.

He had no horse worthy of the 1968 Olympic Games. However in the fall of 1969, the talented jumper Sloopy showed up at the USET for Shapiro to ride. But Sloopy and Shapiro’s first European tour, in 1970, never got off the ground, literally. Sloopy was in a shipping box, waiting on the tarmac to be loaded into the plane, when planes flying close overhead spooked him. “He was going to kill himself getting on the plane.

There was a long waiting period at the airport, and they switched the approach path to the airport. These huge jets were flying literally over his head, and it freaked him out. They sent him back home,” Shapiro said. Shapiro spent the rest of 1970 getting to know Sloopy, who was a Thoroughbred with a big jump and a strong personality.

“He could be a little rough; he was big and strong. Once you were on him and he respected you, he was fine. But you had to be careful; he would take advantage of you,” he said. Loading Sloopy onto a plane for the USET’s 1971 summer European tour went much better, and he and Shapiro tied for the win in the Grand Prix of Aachen.

Courting Disaster

With 1972 came Shapiro’s dream of the Olympic Games. He was selected to ride along with Steinkraus, Kusner and Frank Chapot. Unfortunately, the summer didn’t go the way he planned. At Aachen that year, Sloopy got a virus.

The German veterinarian on the showgrounds employed an antiquated method to prevent the horse from foundering as a result of his fever. “He bled him. He put a big needle in his vein and drained gallons of blood from him,” Shapiro recalled.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He recovered, and they called [USET veterinarian] Danny Marks. He came over and worked on him, and we stayed at Aachen for a little while until he recovered enough to travel.”

Sloopy had lost strength and fitness, but he was on the way back to health when he arrived in Munich three weeks before the Games. “It was touch and go as to whether he’d be fit enough to jump in the Games,” Shapiro said.

“He was putting on weight and getting stronger. He wasn’t as fit as I’d have liked, but he was close.” But then fate struck again. Just a week before the Games, Sloopy landed funny on the backside of a water jump. The subsequent cut on his hind leg required 30 stitches, and the injury was the final blow for a team already thinned to a thread by injuries. Kusner and Chapot were already riding second-string horses.

“We didn’t even know if we’d have enough horses to make a team. There wasn’t a deep bench,” Shapiro recalled. The team needed Sloopy to jump despite his condition, and jump he did. They finished just fractions of a point behind Germany, and in the individual competition, Shapiro found himself in a three-way tie for an individual medal, decided by a jump-off.

“By that point, Sloopy was exhausted,” Shapiro said. “I could just feel him over the oxers; he felt drained. And it was as big a course as you’d ever want to see. But he just kept going.” Sloopy had two rails. Anne Moore of Great Britain rode Psalm to a round with a refusal, but within the time allowed, to pick up just 3 faults for silver. And Graziano Mancinelli of Italy guided Ambassador to a slow clear round for the gold.

“We ended up with the bronze medal, which I was delighted with,” Shapiro said. Shapiro and Sloopy ended the year representing at the fall indoor shows, and then Sloopy was turned out for vacation. Shapiro never rode him again. “He wasn’t returned to the team. That was the end of it,” he said.

Coming Full Circle

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Shapiro juggled riding internationally with another growing interest—harness racing. When Sloopy refused to get on the plane for the 1970 European tour, Shapiro took advantage of the free time to get his harness racing trainer’s license.

Shapiro’s father had owned some Standardbreds, and when Shapiro went to watch them race, he became intrigued.

“I got to meet the trainer, and he invited me out to drive one. I told him the only thing I’d ever driven was a pony with a cart. He told me, ‘It’s not that hard.’ So I drove one at Roosevelt Raceway. I jogged a horse and then worked him, and I thought, ‘Wow, this is a lot of fun,’ ” he said.

Standardbred trainers have to complete a year of apprenticeship, and it took Shapiro longer than most to satisfy that requirement because he was traveling with the USET so much in the early ’70s.

“It took a back seat. I was having fun with the Standardbreds when I could and jumping when I had to,” he said. By 1977, Shapiro was becoming dissatisfied with show jumping as a full-time career. He loved traveling and riding internationally, but he could see that things were changing in a way he wasn’t really comfortable with.

“Bert [de Nemethy] was still there, but I felt like things were changing internally with the organization. I figured I’d leave while I didn’t have any bad taste in my mouth. I just wasn’t having a lot of fun doing it anymore, so I just stopped,” he said.

Shapiro turned to harness race training full time. He set up shop at a farm in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., trading one of his show jumpers for some land and building a facility. He stayed there for 20 years and trained the trotter Bon Vivant to more than $400,000 in career earnings and the pacer Bomb Rickles to career winnings of more than $500,000. “It’s a very different thing to do, but I was able to apply what I’d learned from riding. I think I had a good feel for horses, and I wound up doing a lot of young horses and sen-sitive trotting fillies. That’s what I had a knack for, and I think that came from riding,” he said.

But by the late ’90s, Shapiro was slowing down his racing career. In 1998, he transitioned back to the horse show world, even though he’d never intended to come back in any capacity.

“But once I was done training race horses, I figured I’d do something, because I couldn’t just sit around and do nothing,” he said. Shapiro had planned to ride a little bit, do some clinics, do some judging and train young horses. “I sort of got coerced into showing again,” he said.

“I didn’t have any real intention of getting back into riding and showing again. It just kind of worked out that way.”

In 2002, he reconnected with Elisa Fernandez, whom he’d known for 40 years. She’d competed for Mexico at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, which were her third Olympics. They married in 2002 and began Hayfever Farm in 2007.