The worlds of Clayton and Lucinda Fredericks, eventing’s golden couple, first collided at the Bramham CCI (England) in the spring of 1993. They met, obscurely, over a bottle of horse shampoo, which Clayton lent Lucinda to wash her horse’s stained legs.

By the Burghley CCI**** (England), in September of the same year, there was more than a flicker of mutual interest, and, one week later at the Blenheim CCI***, real progress was made. Two months later, a

make-or-break drive across the Nullarbor Desert in southern Australia, with a mattress in the back of the car, sealed the relationship.

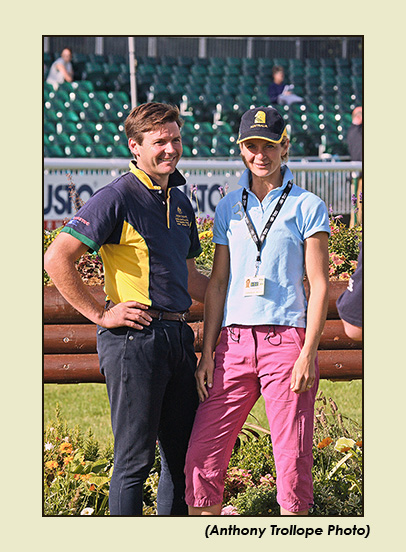

Clayton, 39, the son of a builder from Perth, Western Australia, is handsome and gentle in manner and performs like a dream at karaoke evenings; Lucinda (née Murray), 41, is strikingly elegant and articulate with an astute head for business. They are a glamorous and driven couple, and, with their adorable 3-year-old blonde daughter Ellie, present a wholesome, personable image of the sport.

Refreshingly, they actually appear to enjoy their success, rather than being weighed down by it as happens to some other athletes.

Their spacious, desirable and impressive house, which lies under the rolling, open hills of Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, is stuffed with pictures and trophies that bear testament to an 18-month roll, during which they have amassed World Cup and British Open titles and World Championship team bronze and individual silver medals (Clayton) and, between them, three consecutive four-star victories, at Burghley and Badminton (Lucinda) and Rolex Kentucky (Clayton).

But, both in the words of the song and in the name of Clayton’s current top horse, It’s Ben A Long Time Coming.

Clayton’s first raid on the northern hemisphere circuit immediately yielded 13th place at Bramham with Gage Roads and 25th at his first four-star, Burghley, on Bundaberg. In 1995 he joined the Australian squad, riding as an individual at the Open European Championships. It all seemed terribly easy. But it was to be another 11 years, at last year’s World Equestrian Games in Aachen, Germany, before Clayton finally made it on to the team proper.

Arguably, it was also the first time he was taken seriously as an Australian team member, following in the mold of luminaries such as Andrew Hoy, Phillip Dutton (now riding for the United States) and Matt Ryan.

That quantum leap took some achieving in itself, as the Australian selectors jibbed at Clayton’s decision to skip the Badminton CCI**** (England) in 2006 with Ben Along Time. Instead he won the World Cup qualifier at Chatsworth (England) and, seven days later, the CCI*** at Saumur (France), and they even questioned his personal fitness.

Lucinda, who had finished second at the Luhmuhlen CCI**** (Germany) on the reliable little mare Headley Britannia last June, didn’t make it on to the squad at all. Openly stung by the rejection, she compensated with a resounding Burghley victory—over the favorite Andrew Hoy—two weeks later.

Therefore, many people, especially in Britain where he has a deservedly devoted following, took great satisfaction when it was Clayton whose clear show jumping round under enormous pressure brought the Aussies in from the cold at the WEG and into a medal position, bronze.

As Wayne Roycroft, the Australian coach and Fédération Equestre Internationale Eventing Chairman, draped the medal around Clayton’s neck, the latter reputedly asked: “Are you going to hug me or hit me?”

Clayton explained: “There was a lot of rubbish going on before WEG, and I tried to keep above it. It is difficult for the Australian selectors being on the other side of the world from where a lot of the action is. If you think back to picking a team at school, you tended to choose the people you saw do well, even though someone you haven’t seen might be the best player in the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We have a situation where our selectors have never seen some of our best perfor-mances, and it’s difficult for them, because they get used to seeing the home-based riders doing well all the time. Previously, the selectors didn’t have a great working relationship with British-based riders, but it’s much better now. They’ve made some changes to the way they work, including having ‘Greeny’ [David Green] as a U.K.-based spotter.”

Breaking Into The Big Time

Clayton said the turning point in his career was winning the FEI World Cup Final in Malmö, Sweden, on Peta and Edwin Macauley’s Irish-bred Ben Along Time in September of 2005.

“People say it was only a small field, but it was a pretty good one. I beat the likes of Andrew Hoy, Pia Pantsu and William Fox-Pitt, who are no slouches, and that gave me a real boost. Previously, I’d had a lot of second places, and I suddenly thought: ‘You can do it.’

“It’s much better to work hard and get there in the end, whereas some riders peak too soon. When I finally got on a team, I was well prepared for coping with it. I wasn’t ‘gobsmacked’ at the caliber of the other riders.”

Clayton’s preppy good looks and endearing tendency toward open emotion at his own or—even more likely—his wife’s successes, belie a gritty streak. On leaving school, he conceived the idea, with his mother, of creating a riding center at Perth showground and grew it up to running 200 lessons a week. He was then headhunted to do the same in Melbourne.

His eventing career bloomed, and he was the leading rider in the state of Victoria, but in 1992 he broke his leg in a fall at Wandin and, having sold the Melbourne business profitably, decided to go home to Perth. But intervention came in the form of a “Road to Damascus” moment; driving back across the Nullarbor, he heard the news on radio that Matt Ryan had won double Olympic gold for Australia at the Barcelona Olympics. Immediately, Clayton decided to spend his money trying his luck in Europe.

After the early burst of success, he learned the hard way. “I’ve realized that you have to keep going for it the whole way through a competition,” Clayton explained. “If you’re not the leader at the end of a particular phase, it’s not the end of the world.”

At Rolex Kentucky this year, where Clayton won with Ben Along Time, he was first to go in the dressage on the second day. “[It] wasn’t a great draw, and I was a little disappointed with my mark,” he said. “But I didn’t let it affect me because the main reason I was there was to qualify for the Olympics the next year.”

Despite an intense competitive streak, Clayton said he never leaves the start box thinking that he must go clear inside the time. “I never let the optimum time compromise my setting up in front of a fence,” he said. “I know I’m not the fastest cross-country rider; if it’s a choice between hitting a fence and time faults, I’d rather have time faults. And sometimes I have thought this would be my downfall, but it helped me because my horses then come out and show jump well.”

Lucinda, too, would be the first to concede that she’s not a speed merchant. Fiercely criticized by Mark Phillips in print way back in 1991, she has worked tirelessly on her cross-country riding. Her ambition is to finish inside the optimum time at a four-star, and, despite the recent back-to-back victories at Burghley and Badminton, it remains unachieved, albeit by a couple of seconds.

But what Lucinda clearly has so deservedly achieved is an obvious relaxation, a lessening of the hunger that has possessed her through years of scrabbling for a living and selling the horses that could have brought her individual gloryearlier. Instead, she sought a stable home life after her peripatetic army upbringing.

Those reluctantly passed over horses include, most notably, Beacon Hill, who repre-sented Spain at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, and Simply Red, second at the 2001 Rolex Kentucky CCI under Phillip Dutton. Her best horse, Ballyleck Boy, winner of Punchestown (Ireland) in 2000, had poor feet and never realized his potential, eventually being put down this spring.

“I do feel I’ve done what I want to do now,” Lucinda said. “Winning Badminton is such a lifelong ambition for any event rider,especially for a British person. And it was so hard fought, having led from halfway through Day 1.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Lucinda said she never expected to be in the lead on Friday night. “All my previous wins have been from a position of attack, not defense, and I didn’t have anything like the leeway I would have liked,” she said.

In reliving a tense final show jumping round, Lucinda said: “I tried really hard to stick to my plan, but I needed the fences to be a bit bigger for Headley Britannia. The one time I didn’t anchor her properly, she knocked the fence down. But, funnily enough, that made me relax and I thought: ‘Now I can ride her’.”

A Boon To The Sport

Lucinda’s ebullient and articulate pleasure in her well-deserved victory was arguably Badminton’s saving grace, as the Fredericks family performed a one-family PR service to an event beleaguered by riders’ furious reaction to arriving at the world’s premier competition and being faced withsubstandard ground conditions.

Lucinda’s last words, at an emotional press conference, were: “There are no hard feelings between riders and organizers now. Everything that could be done was done in the end. Next year I’m sure everyone will be wanting to return to the best event in the world.”

Clayton, as chairman of the Event Riders Association, was right in the firing line from angry colleagues. “The riders were on fire even before we arrived. If we’d got to Badminton to see watering, we’d have thought: ‘Oh, they’re on to it’. But nothing had been done. In truth, Lucinda and I were always going to run across country, and in the end the ground was perfectly acceptable, but there needs to be a change of attitude.

“In contrast, right from my first e-mail to Janie Atkinson [director of Rolex Kentucky], she couldn’t have been more helpful. We were given golf carts to get around, and the grooms were given lovely caravans. The briefing and everything else thereon was friendly. It makes such a difference.”

Clayton works tirelessly for ERA and has made great strides in the association being taken seriously and consulted, but he admitted to weariness.

“The problem is that we’re a bit thin on the ground [riders prepared to be active]. Sometimes a rider will get mouthy, and I say to him: ‘We could do with you on ERA’, but they’re not really prepared to put their money where their mouth is. We need to de-centralize from England and get the Europeans involved, and we need a senior rider who is retiring from the sport to represent us at FEI level.”

One of Clayton’s themes is rider licensing, similar to the system seen in racing. “I think everyone competing at four-star level should have a license. We’ve got to get back to riders taking responsibility for themselves and their horse at that level and to be in a position where a rider can lose a license, just like a jockey.

“Now that the roads and tracks and steeplechase phases have gone, problems that might have shown up in a horse earlier will now be manifest on the cross-country. Riders must be more aware of that and of the affect an unpleasant sight will have on the public and on the sport’s image. I can’t remember the last three-day event competitor briefing where we were reminded about welfare of the horse.”

Clearly, the Fredericks are candidates to head up the Australian team at the 2008 Olympics in Hong Kong, where they are already well known as trainers, and their main owner, Edwin Macauley, is vice-president of the federation.

Lucinda, who took up an Australian passport in 2002, has three young horses to compete and, in comparison to her husband, is clearly beginning to slowly wind down her career. But Headley Britannia has produced a live embryo, by the jumping sire Jaguar Male, and Lucinda’s Grand Prix dressage mare, Azupa Gazelle, has also produced two foals, so the next generation is beginning.

“I have to work out what I really need to do,” she said. “And, as ever, I have to be commercial. I’m looking to the future. If ‘Brit’ goes to the Olympics, I will consider one more Badminton in 2009, when she’ll be 16, and then putting her in foal. I know I mustn’t be greedy, because I’ve had so much.

“But Hong Kong could suit Brit, because it will be twisty. And wouldn’t that be the finishing touch to a fairytale story?”

Kate Green