Our columnist evaluates the reasons riders blame their horses and how they might find solutions instead.

It’s disheartening and unbelievable to listen to people blame their horses for anything and everything that goes wrong.

If we all knew more about how a horse thinks, learns, processes and translates things we would be more successful, empathetic, intuitive horsemen.

A horse doesn’t have the ability to plan and rationalize like we do. Horses don’t (and can’t) plot to make you fall off, have a rail down in a jumper class, or spook at something in the corner of the ring. I often hear riders say their horse planned to do this or that to them today. That’s an ignorant statement, as horses don’t have the ability to plan. They are simple-minded animals that react from fear, positive or negative reinforcement, good or bad past experiences, and natural instincts.

Horses remember bad experiences much more than good experiences. So a horse that has a troubled past takes a lot more understanding, patience and good experiences than one without those negative memories.

Spooky horses are usually a product of living in an unnatural environment, with little or no turnout and little or no social life, meaning contact with other horses. Fresh horses just feel good and are quicker to react to sudden movement or new objects. That’s their built-in flight mechanism. It’s not their fault, and the worst reaction a rider or handler can have is to lose their temper, get rough or punish them. This only reinforces to the horse that there is something to be afraid of. Instead, the rider should relax, ignore it and avoid it until the horse is more relaxed.

I strongly believe in always beginning a schooling or training session by walking on a long rein, both directions of the ring, followed by trotting on a long rein, both directions of the ring, to allow a horse to mentally and physically warm up and relax about his surroundings before you ask him to focus on the work you have planned that day. Farther into each training session, horses should have breaks, to mentally unwind. They don’t have long attention spans, and, like school children, they need recess from time to time in order to concentrate.

Results Through Repetition And Reward

Remember, horses are herd animals that operate on fear, flight and understanding of right and wrong. Horses want rules and respect hierarchy, but they really want consistency and fairness in learning. They want to be your partner.

Horses are creatures of habit, and they learn from repetition. Proper and successful training comes from knowledge of these two facts.

When a horse does something wrong, it’s either due to the fact the rider hasn’t properly communicated her wishes clearly enough, or the horse is resentful because he is tired, sore, confused or has baggage from previous experiences.

Instead of having the expertise, patience and time to systematically train a horse through progressive aids, we resort to harsher bits, bigger spurs, draw reins, big whips, conflicting aids and temper.

Aids should always be applied in four steps: allow, ask, tell, demand. Always in that order, never skipping a step, and stopping (releasing pressure) as soon as the desired response is reached. Because they learn from repetition, a horse quickly understands what comes next if he doesn’t respond appropriately. This is training, and this is how a horse becomes educated and lighter to the aids.

The nature of the horse is to please. They want to understand; they want to have a job; they want to have a rider that is their teammate, not their dictator.

A horse that is trained by fear would never die for you in battle. This means that a horse that is afraid to make a mistake will be constantly stressed out with the rider’s demands and won’t learn to think for himself. Whereas a horse that is given responsibility and confidence will learn his job well and embrace it.

ADVERTISEMENT

A horse that feels good about himself and attains a high self-esteem is a real winner and a fun partner.

The worst thing a rider or trainer can do is drill a horse to death. Once the horse does something correctly, reward and go to another subject. Drilling only makes a horse confused, nervous, tired, sore and resentful. A good horseman always knows when enough is enough. A good horseman also knows when the horse isn’t understanding something and finds a different way to explain it. If the horse isn’t going to get it that day for various reasons, a good horseman knows how to backtrack, find some little positive reaction from the horse, and call it a day.

Using Judgment

A human’s most valuable natural aid is their brain. By using a little detective work and trying to understand how a horse thinks, you can really find a better solution in communication. This doesn’t mean more gadgets or stronger hardware. This means learn more about horses!

A good horseman uses good judgment when riding, training and competing. Good judgment comes from years of experience and from making mistakes and learning from those mistakes.

Horses have rails down not because they like to hit jumps, but because a rider has interfered with their job. A rider’s job is to have the correct pace, impulsion, balance and track. The rider’s job is to choose the take-off distance. The horse’s job is to clear the jump. If the distance is too long or too short, it’s the horse’s job to deal with it. But if the rider is pushing or pulling on approach or take-off, the horse’s job has been interfered with. The rider should support the horse in the final strides on approach, not abandon him with the leg and/or hand or get in his way by using driving or pulling aids. The horse can’t see the jump the last few strides. He has already sized up the jump and the take-off distance. Any interference at the last second compromises a clean jumping effort.

Horses should learn early in their training to have self-carriage. This results in a horse that carries its own rhythm and balance, while maintaining pace and impulsion. This makes the horse easy to ride around a course, resulting in simply guiding a horse from jump to jump rather than kicking and pulling to create the correct quality of the gallop.

Respect The Individual

A horse that won’t load in the trailer, allow his ears to be clipped without tranquilizer, stand still for the farrier—these are all problems created by some human at some point in the horse’s life. Don’t blame it on the horse. It’s never their fault. It’s always harder to fix a problem that has become a bad habit rather than to start with a clean slate.

Horse handling and training are best accomplished with patience and horse sense, never emotion or force. Although there should always be goals in schooling, training and competing, there can never be a time restraint.

Every horse is an individual. Some are more sensitive, some more laid back, some smarter, some kinder, some younger, some older, etc. In my experience, gender also plays a role in training and communication. You tell a gelding what to do, you ask a mare to do something, and you find a way to make a stallion think it was his idea—you need to stroke his ego!

I have also found that the breed and bloodlines of the horse can help you understand more about what their character might be. Some breeds are more or less sensitive than others, while some bloodlines are known for specific traits, such as more mellow personalities, etc.

Another very valid item on my list is conformation. If you understand and correctly evaluate a horse’s positive and negative structural aspects, you will have a better understanding of that horse’s physical limitations or strong points when it comes to training. For instance, a long-backed horse that stands camped out behind will have more difficulty with collection, impulsion and lead changes. An educated horseman can be more sympathetic to the possibility that these things might be a challenge, instead of just blaming the horse, putting big whips and spurs on, and terrorizing the horse. Another example is a ewe-necked horse with a high cranial headset and thick throatlatch. This horse will be challenging to train to come on the bit. Not because he is a bad or stupid horse, but because of his physical limitations. A poor horseman puts on a stronger bit, draw reins or other gadgets and cranks the poor horse’s head down until the horse breaks, mentally and physically. It’s not the horse’s fault.

A good horseman identifies the age, gender, breed, conformation, strong and weak points of each horse he works with if he is to be successful in developing an educated, happy horse that is a partner, not a slave.

Another thing to consider is the horse’s job description. Is he suited to the discipline in which the rider is attempting to compete? Many times horses are being made to do something they aren’t suited to do. This is true not only per discipline but also per level of rider. Time and time again, a horse is too young, green or sensitive to be able to cope with a novice rider. On the other hand, many horses know what their jobs are, have a lot of experience and confidence, and would much prefer showing a young rider or nervous adult the ropes. They don’t enjoy being trained on by a professional.

ADVERTISEMENT

There are so many nice jumpers that are too careful, too lazy, too level with their frame and movement, much more suited to the hunter ring. And conversely, there are a lot of beautiful hunters that are too high energy that prefer to go more uphill and to the base that would be better suited to the jumper ring.

A good horseman studies each horse’s strengths and weaknesses to determine which discipline they would be most successful in and doesn’t try to pound the round peg into the square hole.

Bit Of The Month Club

Another example of blaming the horse for our misunderstandings is bits and bitting.

So many riders are experts at obtaining the bit of the month. Not only do they ride and show in whatever is trending, but every single horse in their barn goes in the same bit! They need to consider the experience, sensitivity, job description and construction of each individual’s mouth as well as other pressure points that affect a horse when you pull back on the reins.

Not only should the size of the bit, the type of metal or rubber mouthpiece, the leverage factor (length of shank, lift of a gag, etc.), noseband type and fit of the bridle, type and adjustment of a curb chain, type of ring (dee, eggbutt, loose-ring, full cheek, etc.) be factored in, but I see so many horses that are uncomfortable with different types of bits because they have a low palate and can’t deal with the scissor effect of a jointed mouthpiece.

But No. 1, when a horse isn’t responsive to a simple snaffle, first of all, check their teeth. They may have wolf teeth or be in serious need of floating. It’s easy to label the horse as unruly or bad-mouthed, but it’s never the horse’s fault!

If only they could speak our language and tell us when they can’t bend as much as we want them to bend because they have a fused neck, or can’t jump as high because the hind collateral ligament is hurting them, or they buck when they land off a jump because their feet hurt, horses would be easier to understand.

But we can learn to listen to them and figure out how we can learn more about the nature of the horse. The more I know, the more I know how much I don’t know. Never stop learning, and remember: It’s never the horse’s fault!

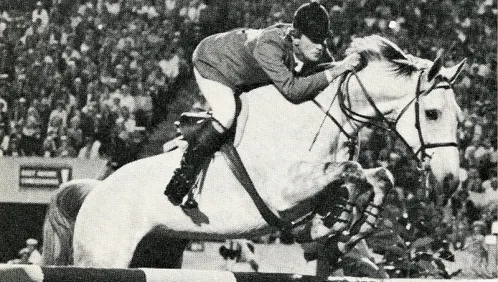

Julie Winkel has been a licensed hunter, equitation, hunter breeding and jumper judge since 1984. She has officiated at prestigious events such as Devon (Pa.), the Pennsylvania National, Washington International (D.C.), Capital Challenge (Md.), the Hampton Classic (N.Y.) and Upperville (Va.). She has designed the courses and judged the equitation finals.

She has trained and shown hunters and jumpers to the top level and was a winner of multiple grand prix competitions and many hunter championships.

Winkel serves as the co-chair of the USEF Licensed Officials Committee and chairman of the USEF Continuing Education Committee, chairman of the USHJA Judges Task Force and the USHJA Officials Education Committee. She serves on the USHJA Emerging Athletes Program Committee, Trainer Certification and Zone 10 Jumper Committees. She also sits on the Young Jumper Championships board of directors.

Winkel owns and operates Maplewood, Inc., a 150-acre training, sales and breeding facility, standing grand prix jumpers Osilvis and Cartouche Z in Reno, Nev. Maplewood Inc. also offers a year-round internship program for aspiring horse professionals.

She writes a monthly column for Practical Horseman’s “Conformation Clinic” and is a contributing columnist to Warmbloods Today magazine as well as an EquestrianCoach.com blogger.