The legendary horseman William Steinkraus died in late November at age 92. He was the first American to win individual Olympic gold in any equestrian discipline: He earned his gold in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games, riding Snowbound. Throughout his career he also won two Olympic team silver medals, an Olympic team bronze medal, more than 100 international classes, and, with his teammates, 39 Nations Cups.

These accomplishments are all the more remarkable given that they’re just a portion of his life’s work. He studied at Yale, served in World War II, and worked in concert management, on Wall Street, and later in publishing. An excellent violinist, he was a director of the New York Chamber Players. He wrote acclaimed books on horsemanship and served as president of the U.S. Equestrian Team, Chairman of its board of directors, and until his death, Chairman Emeritus.

To learn so much more about Bill Steinkraus’ life and career, make sure to read the Jan. 29 & Feb. 5 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse, the Legends & Traditions Issue. Jennifer Calder’s insightful look at Steinkraus is the cover story.

Meeting The Legend

I first met Bill in the springtime of 2016 at the Ox Ridge Horse Show (Connecticut), where my husband, Philip, was riding. Philip had called Bill that morning on U.S. Equestrian Team business. Their conversation (plus the announcer in the background) reminded Bill that the show was on—and not far from his home on Great Island. He decided to come over and watch Philip jump the grand prix.

Amazingly spry and sharp as ever at 90 years old, Bill drove himself to the show, walked to the ring, and found a seat near the in-gate. Since Philip was trainerless, I helped him walk the course and warm up. After he showed, we had the treat of hearing Bill’s analysis and advice—rather a surreal experience, we both felt.

The course was bigger and more technical than Philip had jumped in a while. He rode an excellent round with a couple small mistakes. A rail came down at the B portion of a tight vertical-to-vertical combination, which requires the horse to shorten its stride and rock back on its haunches. A lot of horses were having trouble there, and we knew it would challenge Philip’s mare; she’s big, long-strided and fussy with the bit, which makes tight combinations extra-tough.

Bill sat Philip down beside him and explained that he needed to ride with smoother hands—and not only smoother, but more precise. He said the time to practice this is during flatwork: Let the rotation of your wrists create varying degrees of softness or firmness (thumbs towards each other + hands slightly forward = softer; thumbs up and out + hands drawn back = firmer; try this and you’ll feel your back muscles engage much more in the latter position); teach the horse these cues very clearly as you lengthen and shorten her stride. Then, in the show ring, you can make subtle, smooth adjustments that the horse understands.

Bill took Philip’s hand and demonstrated the varying degrees of wrist rotation and pressure. This was a powerful moment: direct transmission of the great horseman’s “feel” into Philip’s hand.

Philip (right) and Bill Steinkraus. Photo courtesy of Sarah Willeman

After a few minutes of watching, I elbowed Philip aside and got my own chance with the master. I wasn’t about to miss this lesson!

My turn! Photo courtesy of Sarah Willeman

Now, this idea of smooth hands is something that trainers and family members (including yours truly) have been harping on Philip about for years. He’s a gutsy, competitive rider who hasn’t always had very broke horses; he can disregard unruly behavior and somehow just get to the jumps. But finesse—well, he could work on that.

(A side note: To this end, I used to make him watch videos of the German show-jumping superstar Marcus Ehning, an exemplar of smoothness, balance and style. Philip’s main takeaway from this exercise was that I had a crush on Marcus Ehning. For the record, I have a hopeless, incurable crush on his magical feel for a horse, though not on the man himself. But I suppose this is how it goes when spouses advise each other on sports.)

So now the way Bill explained it gave Philip this flash of inspiration and understanding and a new motivation to practice. To put it bluntly, the problem is that when he grabs the reins in pseudo-desperation to slow down, the mare flips her head and inverts her spine—not a good setup to clear the fence. But if he could collect her in one smooth motion, she’d stay round and make a better jump.

In other words, smoother really is better. Beautiful riding is effective riding. Bill Steinkraus embodied this truth and was one of its best teachers.

Philip took Bill’s advice to heart, and his riding improved. A few times, he emailed Bill his videos from other big classes with the mare, and Bill wrote back with kind, elegant, concise feedback.

One example:

ADVERTISEMENT

Dear Philip:

I like your mare. She could have tried a bit harder to not pick up a rub, but I can’t fault either of you very much. You’re thinking “slightly forward,” but with her length of stride she made the distance if anything too easily, and ended up a bit tight to the front rail. Perhaps if you’d have closed your fingers a couple of ounces worth in the last stride, telling her “be careful” she’d have made a little extra effort, but she’d probably leave it up four times out of five, going just as she went.

Kind regards, Bill

And another:

There are lots of good things on your tape, the best yet, but before you jump a fence you should put your horse on the bit and everything will improve.

Regards, Bill

Philip’s mother, the respected horsewoman Judy Richter, took the photos of us with Bill that day. Afterwards she initiated a series of lunches with him, some of which Philip and I got to join—a privilege for all of us, as Bill was fairly reclusive in his later years. I wish I’d had a tape recorder when he talked about horses. He was articulate and dignified, without any sense of egotism. His eyes had this intent brightness: intelligence, but also passion. His passion for horses was evident, after all those years.

Steinkraus Horsemanship

His horsemanship was based on empathy. He thought always of the horse’s point of view, and this mindset made him a classy sportsman and a highly effective trainer. Understanding the horse’s experience helps us communicate with him better. This seems an obvious point, but it often gets lost. Riding is a conversation, and it won’t work unless the horse and rider speak the same language. What a rider sees as misbehavior might be a failure of communication. It’s our job as horsemen to teach the horses our signals and understand theirs.

Bill Steinkraus on Ksar d’Esprit at Lucerne (Switzerland).

“A good horseman must be a good psychologist,” Bill said in a 1968 interview in Life Magazine. “Horses are young, childish individuals. When you train them, they respond to the environment you create. You are the parent, manager and educator. You can be tender or brutal. But the goal is to develop the horse’s confidence in you to the point he’d think he could clear a building if you headed him for it.”

Bill’s book “Reflections on Riding and Jumping: Winning Techniques for Serious Riders“ is among the best classic horsemanship texts. In it he writes:

We must never forget, every time we sit on a horse, what a privilege it is: to be able to unite one’s body with that of another sentient being, one that is stronger, faster and more agile by far than we are, and at the same time, brave, generous and uncommonly forgiving.

Among all the technical instruction—the stuff of dreams for a cerebral horsemanship student—are many pieces of excellent advice that could guide any discipline of riding. First, some general rules:

- Be patient.

- Know when to start and when to stop. Know when to resist and when to reward.

- Make yourself and your horses as fit as possible.

- Outstanding performance depends on a combination of physical equipment, talent, and temperament, any one of which, if extraordinary enough, can largely compensate for fairly ordinary attributes elsewhere.

- Every rider should always have an immediate answer to the question, “what are your and your horses’ main faults, and what are you doing about them?”

- If you’ve given something a fair trial, and it still doesn’t work, try something else—even the opposite.

- For the horse to be keen but submissive, it must be calm, straight and forward.

- Our aids must be totally independent of the business of staying on, and they must function from a stable platform. That platform is our position.

- For the horse, riding is indistinguishable from training; you’re training your horse every time you ride it, like it or not, and after every ride, your horse will have changed in some way, for better or for worse.

On the methods of riding and training:

- Explain with unmistakable clarity how you expect the horse to respond to your aids.

- I cannot stress too much the vital importance of restoring all aids to their normal position as soon as the horse has complied with them.

- Even a relatively sharp stimulus, if constant, eventually loses its effectiveness—if it doesn’t first drive the horse mad!

- The horse is bigger than you are, and it should carry you. The quieter you sit, the easier this will be for the horse.

- The horse’s engine is the rear. Thus you must ride your horse from behind, and not focus on the forehand simply because you can see it.

- Never rest your hands on the horse’s mouth. You make a contract with it: You carry your head, and I’ll carry my hands.

- Good hands will be stable (rather than unsteady); interesting (rather than boring or stupid); refined (rather than crude or clumsy); and fair (rather than arbitrary or punitive).

- Young horses are like children—give them a lot of love, but don’t let them get away with anything.

- With a truly difficult horse, what you are trying to do is create a little island of compliance in the midst of its ocean of resistance, and then gradually to enlarge it… you must sometimes ‘split the difference’ and praise only small improvement, or temporarily abandon an exercise that is fraught with anxiety for the horse and let it do something that it does well.

On jumping:

- Much of the art of jumping lies in riding perfect approaches.

- The better your horse goes on the flat, the more rideable it will be over fences.

- Don’t let over-jumping or dull routine erode the horse’s desire to jump cleanly.

- Practicing difficult lines over rails on the ground provides three-quarters of the benefit of using real fences, without depleting the horse’s energy. You can therefore do them more often, which is an added advantage.

- I cannot overemphasize the fact that it’s the horse that jumps; the rider simply goes with it. You don’t have to make a little jump yourself.

On the mindset of rider and horse:

- The essential ingredients of a sound psychological attitude are a set of realistic, progressive goals, enough maturity to cope with disappointment, and an unwillingness to give up and stop working even when things are going very badly.

- If you can’t always have the best horse, you can try to be the best rider, or even better, the best horseman, for then you’ll have more chances to be sitting on a superior horse as well.

- The harder you work the luckier you get.

- Do as much as you can to provide sufficient variety in the horse’s daily work for it to maintain a fresh and cooperative outlook.

- In addition to daily relaxation on a long rein, every horse will benefit from one day a week of just hacking out in the woods or across country.

- It is important for the horse always to retain a sense of its own volition and spirit; if you dominate it to the point that it becomes only a prisoner, and cannot freely give itself to you, you will never get the best of which it is capable.

- As a general rule, you won’t go far wrong if you settle for a steady improvement rate of 1 or 2 percent a day, even including the occasional day when everything goes wrong, or nowhere at all.

- Less is often more, and since the horse will have the last word in any case, we must try to ensure, through skill, tact and moderation, that this last word is “yes.”

Wisdom for life permeates his teaching. And throughout his long tenure on the US.. Equestrian Team, Bill was known for his class as a person as well as his excellence in sport. Spend a little time with Bill, and you’d come away feeling that he’d raised your game. Read his book, and you’ll feel the same.

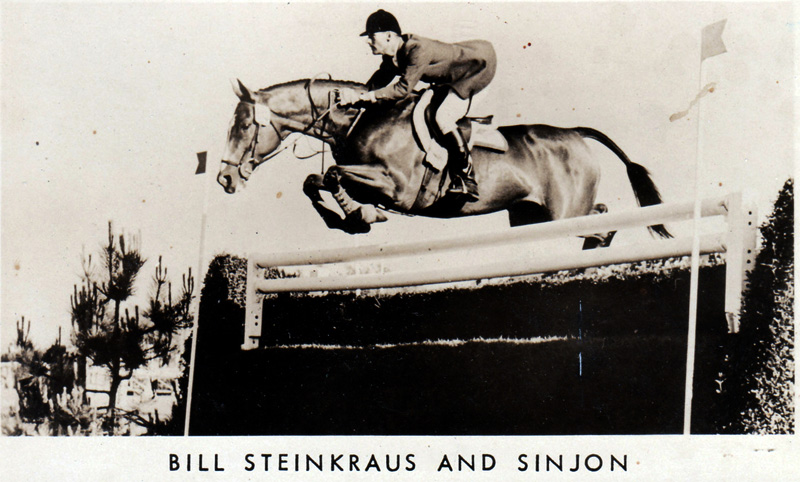

A USET postcard featuring Bill Steinkraus and Sinjon.

Final Memories

The last time Philip and I saw Bill, we drove to his house on Great Island on a chilly spring afternoon. Judy and I squeezed into the back of Philip’s sporty little car, Bill clambered into the front, and we went to lunch at his favorite local restaurant—a casual, clubby place where the waiters knew his name. Over burgers and Bloody Marys, we talked horses and horse business, memories and current events, and after lunch he showed us around his home.

His unassuming trophy cases were packed with old-school silver cups and plates engraved with the great show jumping venues of the world: Aachen, Hickstead, Dublin. Philip and I couldn’t resist a super-fan photo opportunity with the riding crop Bill carried to win the ’68 Olympics.

ADVERTISEMENT

With the crop that Steinkraus used while winning individual Olympic gold in 1968. Photo courtesy of Sarah Willeman

His vast collection of horsemanship books included some that were centuries old. There was a French book on equine conformation called (in translation) “The Imperfections of the Horse,” published in 1763—Bill said he’d owned it about 50 years. We all browsed the illustrations together and remarked on the various startling defects of legs and backs, the different types of the head, the lop ears and Roman nose. On an illustration of a horse with a keen, confident eye, a look of intense focus, Bill said, “I love to see horses that are that way over the fence.”

He clearly enjoyed sharing his books, but it wasn’t a collection for show; he loved and studied these books. He was a scholar in the true sense of the word.

Looking through old issues of The Chronicle of the Horse, he saw a photograph of a rider with low, flat hands and elbows poked outward. “See, she’s locked her elbows and forced her hands down,” he said. “Now, if you do that over a fence, it’s really a wicked thing to do, because you cannot ever have a so-called automatic release.” An automatic release, wherein the hand follows the horse’s mouth with elastic contact over the fence, can’t happen if the elbows are frozen, he explained. He saw this as a serious problem in the modern horse-show world—riders failing to develop an independent, following hand—and he was troubled by it.

“The hand has to be able to follow the head wherever the head goes,” he said, “unless you don’t want it to go anywhere, and you can certainly resist, and you often have to. But the key to that whole mechanism is the elbow.” He said riders get confused; they think put your hands down, and they get into that braced, counterproductive position. He demonstrated it. “The minute you do this,” he said, “you’re introducing a whole bunch of problems that just make your life more difficult—and the horse’s.”

We talked of music, too—he still played his violin—and of the publishing world, in which he spent the last of his working years, at D. Van Nostrand, Simon & Schuster, and Winchester Press, where he was Editor in Chief. He described how infectious a mentor’s enthusiasm can be, how he learned from his mentor in that business to truly love the art of publishing a beautiful book.

We lingered in his library, none of us really wanting to leave. There was a bittersweet feeling that day, an awareness of precious opportunity, to be sitting with this great man, having this glimpse into his world and mind, and mixed with that, a sense of his age and mortality, the solitariness of a widower’s life.

Though he complained of nothing, the only regret he expressed was a wish to have been more up-to-date on the current leading show jumpers, beyond what the news could deliver. “You asked me questions,” he said. “I would love to have had contemporaneous answers for them. I don’t. My answers are all based on past decades, the past quarter century.” Seeing today’s top horses and riders occasionally on video was not the same as studying them live, he felt. “It’s like recorded performances of music,” he said. “It’s way better than nothing, but it’s not the same as being there.”

In all, the strongest sense was of his power of mind, his kindness, his delighted laugh that would break though our earnest conversation. At age 91, he still had this magnetic spark of life.

On our way out, we told him we were going to visit our new foal. He said, “Give him my best regards!”

As fitting a blessing as we could imagine for a newborn colt.

Here, in closing, is a passage from “Reflections on Riding and Jumping” on the best horses of Bill’s lifetime:

Looking back over the great horses I have seen, as well as the considerable number I have been privileged to ride, I am struck by their almost infinite variety of types, sizes, shapes and breeding origins. The only common denominators I can discern are that they were all strong personalities in their own ways; they all disliked hitting fences more than the average horse does (though not all to the same degree); and they all had enough physical equipment not to have to do so. None of them was an easy horse, and only a handful were really beautiful individuals, but they were outstandingly generous and tenacious, and could always seem to come up with an extra effort when in trouble. Finally, each one had as a collaborator a rider who really believed in its ability.

Sarah Willeman won the 1998 Washington International Equitation Classic Final (D.C.) and the USET Show Jumping Talent Search Finals—East (New Jersey) and Pessoa/USEF Medal Final (Pennsylvania) in 2000, as well as many junior jumper honors. She has jumped to the grand prix level and also breeds and rides reining horses. She and her husband, amateur show jumper Philip Richter, run their Turnabout Farm in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

Don’t forget to check out the Jan. 29 & Feb. 5 Legends & Traditions issue of The Chronicle of the Horse, featuring our in-depth profile of Bill Steinkraus and more. See what’s in the issue.