Today we take for granted that equestrian disciplines are the only Olympic sports in which men and women compete on equal footing, but it wasn’t that long ago that remarkable female riders were shattering the glass ceiling. During March, we’re looking back at some of them. A version of this story first appeared in Untacked magazine.

“Not many people ever win a medal at the international level, so when I mention that Lana has won medals in two equestrian disciplines, you begin to realize that you are in the presence of someone special,” explained emcee James C. Wofford at the 2012 Eventing Hall of Fame induction ceremony for Lana duPont Wright. “That those medals happened nearly 20 years apart gives you an insight into her abiding passion for all things equestrian.”

Born in 1939 in Philadelphia, Wright made history by becoming the first woman to compete in Olympic eventing when she was named a member of the U.S. Equestrian Team at the 1964 Tokyo Games aboard her fabled Mr. Wister.

At that time, the USET was training in Camden, S.C., and Wright—never one to brag—recalled that there were, “not a lot of horses around from which to select a team. Olympic selection was more about survival of the fittest.”

Leading up to her historic Olympic debut, Wright had little time to prepare, as the rules were changed only at the eleventh hour to allow women to compete. Her memories of those Games are of big, imposing fences and none of the narrow types we see today. Despite multiple falls on cross-country, she remounted and continued, and the team won the silver medal.

“We fell hard, Wister breaking several bones in his jaw,” Wright recalled in the U.S. Equestrian Team Book of Riding. “We were badly disheveled and shaken, but Wister was nonetheless eager to continue. We fell a second time near the end of the course, tripping over another spread. When we finished, we were a collection of bruises, broken bones and mud. Anyway, we proved that a woman could get around an Olympic cross-country course, and nobody could have said that we looked feminine at the finish.”

“Before Lana, women were the weaker sex; after Lana, women joined one of the few Olympic sports where men and women compete on an equal basis,” Wofford said at the 2012 ceremony. “Considering that eventing competitors are currently 88 percent female, I would especially like for the ladies in the room tonight to consider a time, not so long ago, when a glass ceiling existed. We now take it for granted that women will stand on an Olympic podium, but until Lana came along, that was not possible.”

Wright’s earliest memories of horses all include her mother, Allaire duPont, who was a keen foxhunter and breeder of the legendary race horse Kelso.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I would go out and hunt with her any time I could,” Wright said, noting how much she also learned about horse care from her mother’s groom. “he taught me everything.”

As a teenager at Oldfields School, an elite boarding school in Maryland, Wright began to focus more seriously on riding.

“My senior year I was able to go in my first event,” she said, adding quickly that she knew very little about how a competition went. “I didn’t even walk the course. [But] no one knew anything about the sport and everyone else lost their way or got eliminated, so I ended up winning; it made me very hungry.”

That hunger led Wright to Vermont, “Where Gen. [John Tupper] Cole and [Capt. H.] Stewart Treviranus held a clinic,” she said. “Trish Gilbert was there; we built the cross-country and the steeplechase courses. How primitive it was in those days. That was where I learned a little and also did more dressage with Richard Watjen at Sunnyfield farm in New York.”

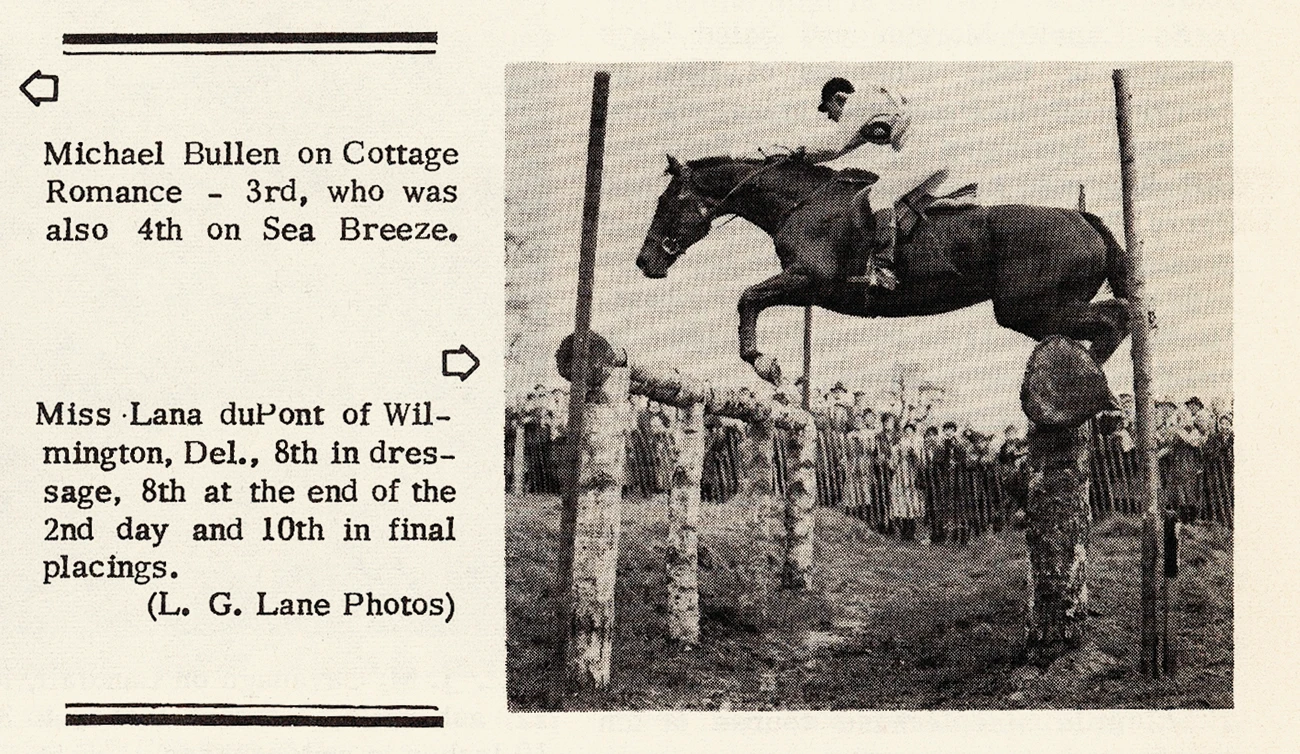

In 1961 Wright realized her dream of competing at the Badminton Horse Trials (England), prior to which she spent two months in training with the legendary Capt. Edy Goldman.

“Mr. Wister was one Mother had given me off the racetrack, so I made him,” she said. “He was a bit of a rogue and could buck me off whenever he chose, but after a year or so he was all changed; he was awesome and took me to Badminton.”

Eventing in the United states was still very much in its infancy, so arriving at Badminton was “an eye opener,” she admitted. “But we did get around; we did all right.”

The 10th-place performance helped earn them their Olympic berth.

“It was a great experience, and when I look back I couldn’t have done any different, because I was learning the best way I could,” Wright said of her eventing career. “The more you ride, the more you learn.”

Following the Olympic Games, Wright focused on her family and foxhunting. She and husband William Wright, a trainer and veterinarian, had two daughters: Lucy and Beale (who was a successful event rider until her premature death from an illness in 2005).

ADVERTISEMENT

But as an ambitious equestrienne with a quiet competitive streak, Lana was not content to rest there. So she mounted the box seat and garnered more international success.

“I took to driving when my eventing days were over because I didn’t have a horse to ride,” said Lana, who went on to win team gold at the World Pairs Driving Championships with her Connemara ponies in 1991. She also founded and organized the Fair Hill Combined Driving Event in Maryland.

And later, “because I just loved to investigate the countryside and would go out riding for miles without telling anyone,” she took up endurance riding, completing many 100-mile rides.

Lana will be remembered as a pioneer for women in eventing, but those who met her in the hunt field or watched her driving or endurance riding will attest to the many attributes that make her an all-round horsewoman worthy of a place in the history books.

“Lana is unparalleled, and her achievement is incomparable; there never was anyone like Lana, and there will never be anyone like her again,” Wofford said. “In years to come, eventers will look at the list of Hall of Fame members, and they will say, ‘Once upon a time, there was an inductee like Lana duPont Wright… But only once, for she is indeed unique.’ ”

But for her part, of course, the intensely shy and humble horsewoman demurred.

“I was never good enough,” she said. “But I really respect the great riders, especially the English riders. They deserved to go to the Olympics first I think, not me. But I was there.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Summer 2014, issue of Untacked. You can subscribe and get online access to a digital version and then enjoy a year of The Chronicle of the Horse and our lifestyle publication, Untacked. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.