In the second of this three-part series about “the mollification of American show jumping,” our columnist looks at the way our courses used to demand determination.

Much like our Thelwell ponies and difficult horses taught us physical and mental toughness, the sport itself and the courses demanded it. In the second part of this series, we discuss taking care of the horse and teaching the horse.

Most shows had permanent outside courses for hunter competitions when I started riding as a junior. Devon (Pa.), Junior Essex Troop (N.J.), Ox Ridge (Conn.), Fairfield (Conn.), Chagrin Valley (Ohio), Jamesburg (N.J.) and New Brunswick (N.J.) all had outside courses with permanent brushes, walls, and posts and rails. It was galloping and jumping without the need to count strides when there were 20 of them between fences. The gates were straight, and the walls were solid. Our small ponies had to jump 2’6″ and 24′ in-and-outs. We only had a 50-50 chance of making it in one stride, but we kept trying.

The first year I went to Junior Essex Troop to ride in the large pony hunters, I couldn’t wade across the stream to get to the start of the outside course in two out of the three classes, but I made it across by the last one. The next year we were reserve champion. That’s the way it was. You didn’t complain. You figured it out and got better. Again, it took grit.

Chaps Are For Working

It also took hard work.

“You’re lucky you don’t have to morning feed and do stalls at home!” Dad didn’t mince words when he was angry. Complaining about picking rocks out of the field was not getting us any sympathy. It was mid-summer, and the turnout fields were getting some rocks. The horses needed turnout between shows, and making sure they wouldn’t get stone bruises in the paddocks was part of the job. Provided we took care of them, we could have them.

ADVERTISEMENT

Although things changed later as we progressed from local C-rated shows to the international arena, that’s what we did. We took care of our horses: turnout, leg care, feeding, shipping, clipping, packing feet, medicating, flatting, schooling and training; showing was the ultimate reward. When we went to the show, we set up, got some horses out, put the horses away, declared our entries for the next day, had dinner, and then did night check. We knew our horses from the bedding up.

Unless you were showing or in a U.S. Equestrian Team clinic, riding attire was blue jeans with chaps and paddock boots—even when riding in lessons with George Morris! He wore boots and breeches, but he was the instructor! We wore jeans because after the lesson, we were getting off, taking off our chaps, and getting to work washing the horses, cooling them down, wrapping their legs, and preparing them to ship home. When we got home, we unloaded them, fed them and put them away. If there was a problem, we stayed until it was resolved or the veterinarian arrived.

That’s how we spent our summers during high school. We earned the privilege of riding and showing by taking care of our horses. We did it all. You can’t take care of horses wearing fancy boots and breeches. If boots and breeches is your barn attire, you are an equestrian consumer, not a horseman. No disrespect, but training attire for horsemen is dirty pants and muddy boots.

Serving In The GHM Cavalry

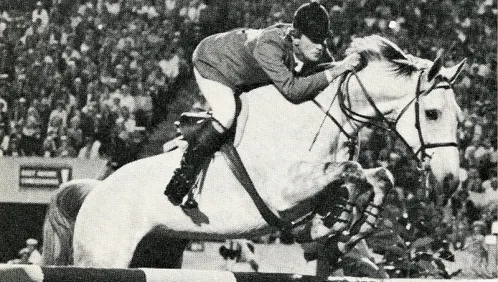

Just ask Morris. There was a joke that we shared with him: We didn’t have to go into the military to get toughened up; our fathers could just send us to ride in the cavalry with Morris. He trained us hard and without sympathy. “Over, under or through” was the motto. We were trained over every type of natural obstacle imaginable because Morris’ field, and our family field later, was designed to train a horse to jump the Hickstead Derby (England), the Aachen Grand Prix (Germany), the Hamburg Derby (Germany), Fontainebleau (France), the International Jumping Derby (R.I.) and Spruce Meadows (Canada) with their ditches, banks and waters, alone and in combination.

Riding then was a contact sport, and we played for real. The ditches were two feet deep. The water jumps were concrete and two feet deep in the middle; they were typically jumped only half full, making it a big blue ditch with a puddle in the middle. The banks were big and rough. Mistakes were not forgiven easily and were to be avoided at all costs. It was truly riding at the edge of the envelope. It was physical, and it was real. Morris made us overcome our fear and taught us how to take our horses through these obstacles and overcome their natural fear and anxiety jumping them. They’re called courage jumps for a reason. It was exhilarating but never fun jumping these obstacles, until you got to the other side—because until you got to the other side, you had to focus on getting it done safely.

Teach One To Know One

ADVERTISEMENT

If you haven’t taught a horse how to jump a ditch or a real water jump, you can’t appreciate how important it is to preserve a horse’s willingness to jump it once you get it. There is no removing the element of danger for horse or rider when jumping these jumps. The risk of hesitation or stopping, swimming or crashing, is too great to ever take these types of obstacles for granted. They have to be jumped with a different attitude, position and balance than a fence built of rails. The art of the override once ruled. It ensured the rider’s and horse’s safety while maximizing the clear effort.

Natural obstacles require both rider and horse to confront their fear. There is no soft way around this. Riders must conquer their mental fear, suppress it, and provide the confident leadership to help the horses conquer their mental fear. There is no half-heartedness when jumping these obstacles; half-hearted rides end up in catastrophe. There is a necessary component of tough love when teaching a horse to overcome its natural avoidance of ditches and waters. You can’t teach a horse to jump natural obstacles if you don’t have a solid position, discipline, guts and knowledge.

The problem is that most riders today don’t have the depth of seat, knowledge and grit to ride these jumps. Most trainers don’t either. The sad answer to this problem has been show management’s removal of natural obstacles from their competition venues, leaving only poles and planks to jump. This creates a negative feedback loop that further decreases our riders’ ability and willingness to learn how to jump these obstacles. So, the less capable our riders become, the less demanding the courses become.

So what happens next? I share my thoughts on the future of American show jumping in Part 3 of this series.

Armand Leone Jr. of Leone Equestrian Law LLC is a business professional with expertise in health care, equestrian sports and law. An equestrian athlete dedicated to fair play, safe sport and clean competition, Leone served as a director on the board of the U.S. Equestrian Federation and was USEF vice president of international high performance programs for many years. He served on USEF and U.S. Hunter Jumper Association special task forces on governance, safety, drugs and medications, trainer certification and coach selection.

Leone is co-owner at his family’s Ri-Arm Farm in Oakland, N.J., where he still rides and trains. He competed in FEI World Cup Finals and Nations Cups. He is a graduate of the Columbia Business School in New York and the Columbia University School of Law. He received his M.D. from New York Medical College and his B.A. from the University of Virginia.

Leone Equestrian Law LLC provides legal services and consultation for equestrian professionals. For more information, visit equestriancounsel.com or follow them on Facebook at facebook.com/leoneequestrianlaw.