Manhattan has never been the most natural setting for a hack or a handy hunter class, but this bustling New York City borough still boasts a unique and rich horse show history.

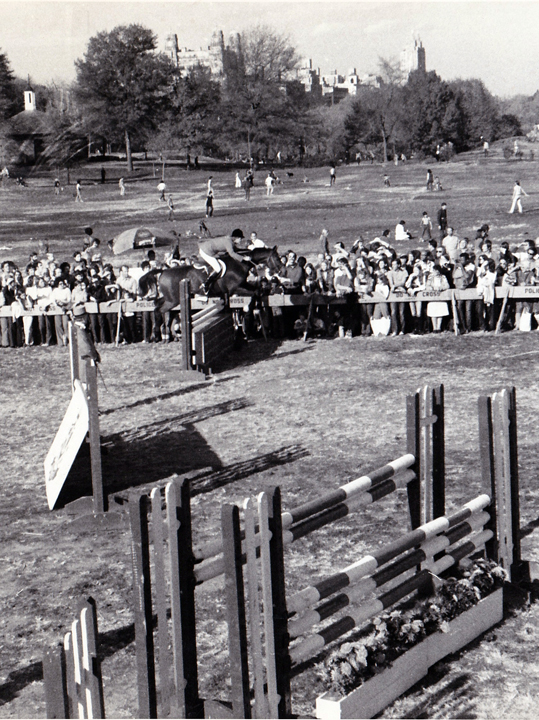

The uninitiated clustered four and five deep along wooden sawhorses lining the makeshift show ring.

They stood on tiptoes, children on shoulders, to catch a glimpse of the illustrious riders and famous horses soaring over jumps.

The skyline of Manhattan stood in crisp contrast to Central Park’s Sheep Meadow, where the last brightly colored autumn leaves clung to the trees.

Bill Steinkraus, the five-time Olympian and the 1968 individual gold medalist in show jumping, had been recruited to provide commentary. He stood smiling, microphone in hand, with “The Voice of the National,” renowned announcer and trainer Victor Hugo-Vidal.

Then-captain of the U.S. Equestrian Team Frank Chapot piloted the dappled gray Good News Joe around the course as his wife, Mary, and their young daughters, Laura and Wendy, laughed and watched. Nearby Rodney Jenkins warmed up Shazzar, the mount he borrowed from Mary for the occasion, while 19-year-old Buddy Brown, the youngest member of the U.S. Equestrian Team, awaited his turn atop the famous Sandsablaze.

Ted Cushny, the last National Horse Show president (after his tenure the show would be run by the show committee chairman), wandered about, delighted by the large crowd.

Held for two years (1973 and 1974), the Central Park Mini-Show was the inspiration of public relations maverick Barbara Stone Halpern to promote the venerable, then-90-year-old National Horse Show at Madison Square Garden.

|

| Legendary horsemen Victor Hugo-Vidal (left) and William D. Steinkraus donned their dapper street wear to emcee the Central Park Mini-Show on a crisp autumn day in 1974. Photo courtesy Barbara Halpern. |

Moving from the dark, cavernous Garden and into the vivid outdoors, the public demonstration highlighted some of the most accomplished riders in the world and marked, surprisingly, the first ever horse show of its kind held in Central Park. It was repeated one time in 1981 on the Great Lawn (also as a preview for the NHS), but in the three decades since, Central Park never again welcomed the top horsemen in the country, nor has it ever hosted a standalone, high performance event.

Until now.

* * *

On Sept. 18, horses and riders from around the world will converge on the Trump Rink in New York City’s Central Park for the first annual Central Park Horse Show, presented by Rolex.

This four-day festival, the first of its kind held in Manhattan, will include exhibitions of various horse sports, matinee performances with ticket giveaways to local children’s groups, Sunday Polo in the Park, a live televised $200,000 grand prix show jumping feature and a “USA vs. The World” freestyle dressage competition showcasing some of the top combinations in the world, all set against the beautiful backdrop that is autumn in New York.

For more information or to purchase tickets to the event, brought to you by The Chronicle of the Horse, visit CentralParkHorseShow.com.

* * *

| This story originally appeared in our Fall 2014 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse Untacked. To read more stories like it, subscribe now. |

A Perfect Stunt, A Public Stage

Halpern had plenty of ingenious ideas to promote the National, but her Central Park Mini-Show was probably the most ambitious. Just 23 at the time, she was undaunted when tasked with reversing a trend of declining ticket sales.

The job was a natural fit for Halpern, a lifelong horse lover who as a teenager often took three buses from her home in Providence, R.I., to get to a lesson barn. Throughout her childhood she obsessively entered the annual Kentucky Club Pipe Tobacco Derby Day Contest to name a race horse, convinced her submission would be picked and that she’d win the grand prize: her own horse.

“I always made my pediatrician buy this Kentucky Club tobacco so I could send in my entry blanks, and every year, I wouldn’t win,” recalled Halpern, who’s now 65 and an avid competitor in the adult amateur hunters. “And I’d curse the man who ran the contest, thinking he must be terrible.”

Just a few years later, as she entered a PR office on Madison Avenue for a job interview, she noticed posters advertising the Kentucky Club decorating the walls. That “terrible” man, Ted Worner, was about to become her boss.

Worner’s firm handled promotions for many liquor companies, including Courvoisier, with its logo bearing Napoleon crossing the Alps on a white horse. So they established a contest similar to the Kentucky Club’s, giving away a white Arabian—which Halpern was tasked with finding—at the National.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I came up with the idea to use New York City as a venue to publicize the horse show and the Arabian, and I decided a good location would be the Abercrombie & Fitch building on Madison Avenue,” she said. “It was a very fancy, elegant store at the time, different from the image it has now.

“They agreed to let me host a party on the rooftop of the building that first year,” she continued. “I brought Zora [the Arabian], trainer Ronnie Mutch and USET member Robert Ridland. We took the horse up in the elevator, and they got a lot of attention and press.”

|

| The Manhattan skyline played a beautiful backdrop for the 1974 Central Park Mini-Show. Photo courtesy Barbara Halpern. |

These efforts would result in Halpern being hired as the National’s publicist. In her two years in the role, she devised numerous ways to increase patronage, setting up unprecedented partnerships and promotions with mainstream fashion labels like Gucci and Hermès as well as shopping boutiques in the plaza of the Garden with horse-oriented vendors, such as Vogel Boots.

“Hank Vogel told me he never sold more boots than he did that week,” she said with a laugh. “I asked him to give a free pair to Rodney Jenkins as a thank you to Rodney for letting me use him on a poster.”

To Jenkins and many others, the National was something magical, well worth his time in helping to promote.

“It was always my favorite time of year and my favorite show,” he said. “It was one of those shows where you kind of took it at pot and luck. There wasn’t a lot of training you could do, [the space] was so tight. I loved it, to be honest. I loved showing there.”

His memories of the Central Park Mini-Show promoting it, however, are hazy.

“I remember going there, but that’s about it! That’s awful, isn’t it?” he said. “You’re on a horse in the middle of New York City in Central Park! Maybe we should forget some horse shows, but not that.”

But those hazy recollections by riders are just fine by Halpern, whose objective was not to create a memorable or financial opportunity for the participants, but to expose equestrian sport to a wider audience—a goal that’s as relevant today as it was back then.

“I spent a large part of my childhood visiting New York City, so it was particularly thrilling to have an opportunity to exhibit a quality show horse right in that same milieu, with the skyscrapers in the background,” she said. “Besides promoting the Garden in the media, the Mini-Show brought recognition of fine horsemanship to the many cyclists, joggers and nannies with baby carriages frequenting the park that day. Quite a few chance spectators made their way to Madison Square Garden to watch.”

When The National Was The Garden

Today the juxtaposition of horses and New York City is such an anachronistic marvel that it’s easy to forget the integration of their histories. Long before subways rumbled beneath the streets and impatient car horns blasted, the clip-clopping of hooves provided the background noise of the city, both as methods of transport and for pleasure riding.

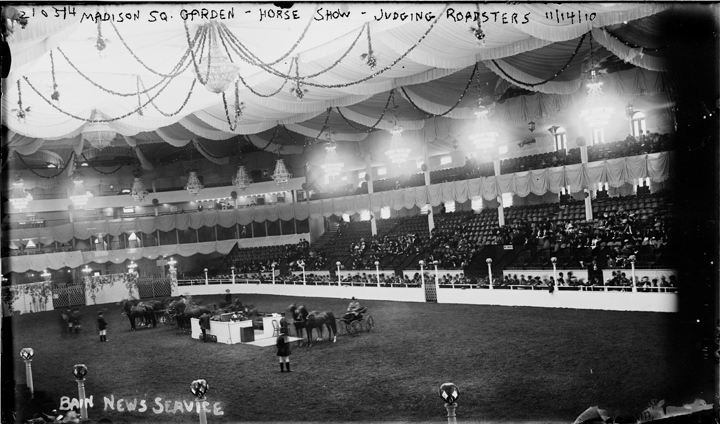

It is from this interdependent relationship that the National Horse Show was born in 1883, followed by the Association of American Horse Shows (later known as the American Horse Shows Association and now the U.S. Equestrian Federation) in 1918. Manhattan would play home to the former for more than a century, until 1989, and the latter for 81 years, until 1999.

Long the most prestigious (and only) indoor show in the country, the National or “the Garden” (both interchangeable shorthand for the event) was founded by a group of affluent New York sportsmen and would, within four short years, count 920 members in its directory. This list would birth the city’s first Social Register.

The Metropolitan Opera commenced that same year—1883—and every autumn the two events marked the kick-off of the opulent social season.

|

| The 131-year-old National Horse Show was synonymous with Madison Square Garden, in the heart of New York City, for more than a century. This image from the 1910 edition of the prestigious competition was taken at the second Garden, but all four iterations of the iconic Manhattan venue hosted the show at one time. Photo courtesy Library of Congress. |

“The National was a special show in part due to its rich history; most people have no idea of what the horse community was like in the city before the advent of the automobile,” said Steinkraus, whose involvement with the National spanned 40 years in a variety of capacities, including as preface author and editor of Kurth Sprague’s exhaustive book, The National Horse Show: A Centennial History, 1883-1983.

“The interesting thing to me was when I was young, quite a bit of that horse culture still existed in New York City,” he continued. “Saddlers, carriage-makers, horse auctions—they all still existed. Then, post-World War I, with the advent of the automobiles, everybody had cars—lots of cars. And all that disappeared in a couple of generations. I think there were five saddle makers in NYC in the ’30s, and now there is just one [see sidebar].

“The horse culture used to be more celebrated,” Steinkraus added. “The National had a real PR department, and they did a lot of promotion on Fifth Avenue, where the windows were decorated in that theme.”

After 106 years, the National’s reign at the Garden, which called several different structures home over its history, finally came to a close.

“It was all very strange—unlikely, unexpected, really—this business of holding a horse show on the fifth floor of a building put up over one of the world’s biggest railway stations,” Sprague wrote of the Garden’s final location, over Penn Station.

|

“I Rode At The Garden” ADVERTISEMENTClick here to read the favorite memories of some of the nation’s greatest riders, from Rodney |

Eventually the effort of converting a hockey rink and basketball court to a show ring, combined with other logistics like shipping and unloading horses, unions, constructing temporary stalls, and leading horses up and down flights of ramps, became too burdensome and too expensive.

Practicality prevailed over tradition in 1989, when the National moved to the Meadowlands in New Jersey. It returned to the Garden for a brief time, from 1996-2001, then for a six-year period its prestigious equitation final, the ASPCA Maclay, split from the show. In 2002, the class was staged at the Washington International Horse Show (D.C.), and in 2003 and 2004 it was held at New York’s Pier 94, at what was dubbed “The Metropolitan National Horse Show,” while the National itself moved to Wellington, Fla. In 2008 the NHS reunited with the Maclay in Syracuse, N.Y., and they moved to Lexington, Ky., three years later.

“In the new Millennium, the National has been obliged to become an itinerant—a victim of Madison Square Garden’s bottom-line priorities and the horse’s declining role in our thoroughly mechanized culture,” said Steinkraus. “Today the National and the Maclay are both ensconced at the Kentucky Horse Park, where they stubbornly cling to a considerable measure of their traditional prestige in the equestrian world. The National may not be ‘the Garden’ anymore, but it still ranks high among the survivors of a very challenging era for equestrian sport.”

The Big Apple On Horseback

But Manhattan has still provided a rich backdrop for a variety of other equestrian endeavors over the years. In 1914, a 12-mile endurance race began in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, wound through Central Park and ended in the show ring of Madison Square Garden, then located at 26th Street and Madison Square Park.

In 1997, Rockefeller Plaza hosted an “Equine Extravaganza” to promote the National Horse Show, and in 2012, eventer Buck Davidson and his four-star mount My Boy Bobby made an appearance in Times Square to promote equestrian events at the Olympic Games.

|

The Last Saddlery Standing Click here to read about Manhattan Saddlery—opened in 1912 and |

In 2010, Britain’s Prince Harry played a charity polo match on Governors Island, the Financial District’s skyline towering in the background. And the dazzling white Lipizzaner stallions of the Spanish Riding School of Vienna have visited Manhattan many times, performing for delighted fans on bustling city streets and in Central Park.

In addition to the famous equestrians who converged on Manhattan for a week every autumn, the city had an equally dynamic relationship with a contingency of pleasure riders who cantered along Central Park’s groomed bridle paths for generations.

Stables were plentiful in the city prior to WWI, but as automobile traffic increased, saddle horses were slowly driven out of the city until one lone stable remained: Claremont Riding Academy.

Located at 175 West 89th Street between Columbus and Amsterdam, and less than two blocks from Central Park, Claremont started as a riding school in 1927 and was housed in a funky, multi-story building constructed in 1892 as a public livery stable.

Looking more like a tenement building than a riding school, Claremont kept its horses both upstairs and down, navigating wooden ramps between floors. There was a small indoor ring on the ground floor—its paneled walls painted green and white—punctuated by closely spaced columns supporting the upper floors.

|

Among The Lucky Ones: Click here to read contributor |

As treacherous as this ring could feel to the beginner, the real adventure started when a rider guided her horse out the stable doors and onto West 89th Street, heading toward the park. The horses that waited patiently at the light to cross Central Park West and shared the street with buses and taxis gave new definition to the term “bomb-proof” [see sidebar].

Claremont’s tradition continued until 2007, when, due to financial constraints and the degradation of the six miles of bridle paths weaving through the park (once reserved strictly for horses, they’d transitioned to running, biking and dog-walking trails), the stable finally closed its doors.