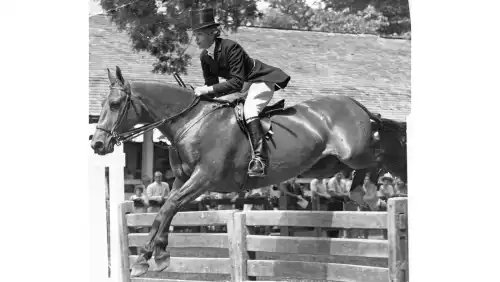

By the time that Pennsylvania National Horse Show rolled around in 1977, where this picture was taken, Dennis Murphy had ridden for the U.S. Equestrian Team in both the 1975 Pan Am Games and the 1976 Olympics on Do Right, in addition to being a valuable part of the team in shows around the world.

Dennis Murphy and Tuscaloosa at the 1977 Pennsylvania National.

But in the wings was this horse—a chestnut Thoroughbred gelding named Tuscaloosa who was being brought along to be Murphy’s winningest horse in the future.

To understand the success that Dennis Murphy had with Tuscaloosa, one should know the story behind the man that was a dominant force in show jumping in the 1970s and 1980s.

Born to a non-horsey family in Alabama, Murphy didn’t have his start as many riders did. He grew up a sharecropper’s son who was raised by his grandparents on their farm. It was on that farm that Murphy got his start with the farm horses. From there, the 8-year-old who loved horses went to a local livery stable. He took on any job at the stable that was available just so he could be around horses—grooming, exercising, trail guiding—you name it, he did it. At 12, he became friends with a girl named Mary Ellen Adams, who owned a horse at the stable. When no one was looking, Murphy started jumping her horse.

By the time he was 15, Murphy was riding anything he could and winning at the local shows. He went to a clinic in Atlanta given by Bert de Nemethy (longtime coach of the USET’s show jumping squad). It was there that Murphy figured out that if he continued the path he was on, he couldn’t make it in the horse business at the highest level because he didn’t have competitive horses nor the money behind him to rise to the top.

When he was 25, Murphy took a job with the CEO of Gulf States Paper Company, Jack Warner. Even though he worked in the Forestry Division, part of the job was taking care of Warner’s horses and going to the shows with him. Soon, Murphy was riding with his boss and Warner found out just how great a rider he was and how good he was at figuring out what makes a horse “tick”.

Warner said “A kid like Dennis, who doesn’t have a rich momma and daddy, he’s got to have somebody helping him. A poor man can’t do it.” Warner became that somebody.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1973, Murphy, then 30, went to Gladstone, N.J., for the last set of trials for the USET’s jumping squad. He didn’t have the fanciest horse at the trials nor did he have the fancy tack and clothes that others had, but Murphy had the desire and the natural talent so he was one of four selected to be taken under Coach deNemethy’s wing in preparation for future Nations Cup competitions as well as the 1975 Pan Am Games and the 1976 Olympics. From the trials, Murphy became a valuable part of the USET.

USET coach Bert deNemethy is quoted in a Sports Illustrated article (November 25, 1974) titled “A Country Boy Has Them Jumping”, written by Ray Blount Jr. “I never saw Dennis before,” he said. “I never heard his name. For the last set of trials, in Gladstone, N.J., he just applied and arrived, and look, the man is like a cowboy. What he’s doing is coming only from the natural instinct. Whatever you can tell him, he can only be better, but it is so obvious! The rider and the horse together, in a harmony with the center of gravity! This is what you can notice, and from nowhere! From Ollabonna! People from the West Coast and East Coast are being taught from little kids and they come to the trials at 18. Dennis is so much older. You don’t want to realize that somebody without your knowledge is so good. But Dennis has the natural feeling, the feeling for the rhythm, and the balance. That you cannot teach!”

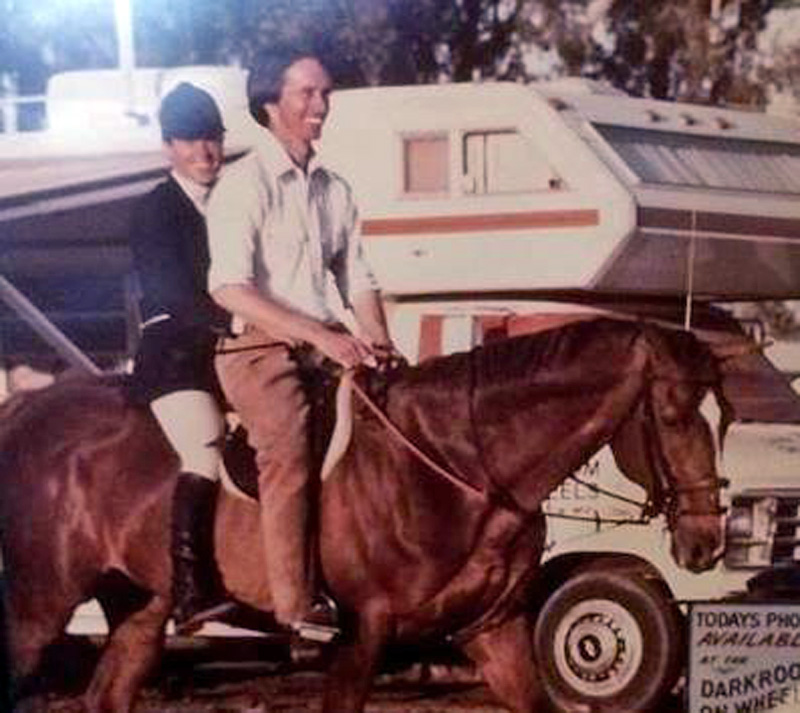

Dennis Murphy and Joan Boyce riding Tuscaloosa around in Florida in the early ’80s.

As Murphy was learning the ropes of show jumping with Do Right and others, he also did some breaking of young horses for a neighbor named Emmett Cloud. One of those was a chestnut gelding named Tuscaloosa—by the imported French stallion *Coffee Money, out of a Blue Murmur mare.

Tuscaloosa was soon sent to Mickey Walsh (Racing Hall Of Fame, Show Jumping Hall Of Fame, and National Show Hunter Hall Of Fame inductee as well as being Little Squire’s owner and rider) to become a steeplechase horse but Walsh said that he couldn’t keep him sound and couldn’t find out what was wrong with him. He asked Cloud to come pick him up.

Murphy was sent to Southern Pines to pick up Tuscaloosa. When he arrived, Walsh told him that the horse couldn’t leave the farm until the $3,000 bill was paid. Murphy called Cloud and told him what Walsh had said. Cloud refused to pay the bill. Murphy relayed that message to Walsh who suggested that Murphy buy the horse himself. “I’ve only got $1,500 to my name,” replied Murphy.

Walsh wouldn’t take that amount so Murphy got in the truck and started out the drive only to be hailed down by Walsh who agreed to the $1,500. Murphy was now the owner of the unsound 3-year-old Thoroughbred.

When they arrived back in Alabama, Murphy took his new unsound horse to Auburn University’s vet school. The Auburn vets took x-rays and saw what the vet in Southern Pines had missed. The x-rays showed a bruised navicular bone in one of Tuscaloosa’s feet which was why he would come out the stall sound and then get increasingly lamer as the work continued.

ADVERTISEMENT

Murphy designed a shoe and metal pad that covered the entire sole of Tuscaloosa’s injured foot. It protected him from more bruising. That shoe and metal pad combo did the trick for the next two years. After that, Tuscaloosa was sound without the aid of pad.

Tuscaloosa was sold to Murphy’s benefactor, Warner. Like Murphy’s other great horse, Do Right, he showed under the ownership of Gulf States Paper Company (Warner’s company).

Many horses, back in the day, that became jumpers started off in the hunter divisions. That was Tuscaloosa’s path. He was brought along through a couple of years of showing in the hunter divisions and then moved up to the jumpers. The first two years of Tuscaloosa’s show career, he showed in the hunter divisions with Warner riding.

After that, Murphy took over the ride on Tuscaloosa. He showed him first in the speed classes before moving him up to the grand prix. Tuscaloosa won his first grand prix at the age of 10 and continued showing and winning until he was 14. He was known for incredible speed on course. Tuscaloosa won all over the East Coast, at the National Horse Show (N.Y.) and the Washington International Horse Show (D.C.) and in Europe.

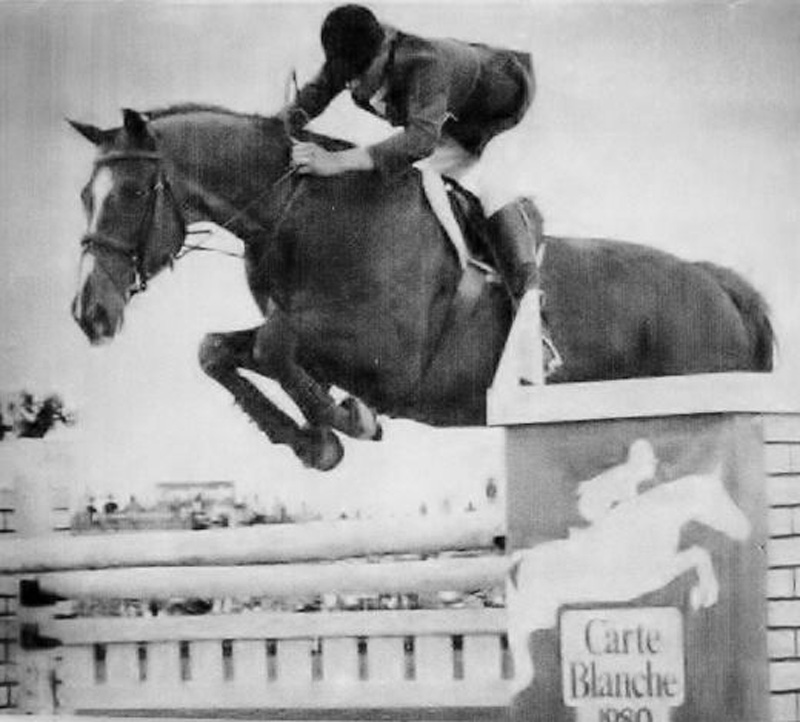

Tuscaloosa and Dennis Murphy winning a grand prix in Florida in 1980.

Murphy said, “Tuscaloosa was the winningest horse I ever had. He loved showing. At home, he wouldn’t school well but as soon as he got to a show, he lit up and was a different horse. He liked galloping down to the jumps which was just my style. We won classes at all the major shows in the United States, Canada, and Europe. He showed for over 10 years.”

Tuscaloosa lived out his life at Murphy’s farm in Alabama. He passed at the age of 29 and is buried on the farm.