As Charles “Sonny” Brooks drove down the dead-end street toward the final house, his great-nieces and nephews stopped playing in the yard and came running over, eager to see the horse he’d brought along this time.

This one was a gray gelding—athletic but ornery—and as the children approached Brooks warned them, “Do not try to pet that horse because he will try to bite you.” Naturally, the temptation was too great, and a few suffered the consequences.

“But he was as gentle as a lamb when Sonny had him at the bridle,” recalled Kevin Sells, Brooks’ great-nephew. “It was like Sonny’s presence calmed him down. I remember seeing that horse in the stable once, and it took two handlers. He always took two handlers, but if Sonny was up it wasn’t a problem.”

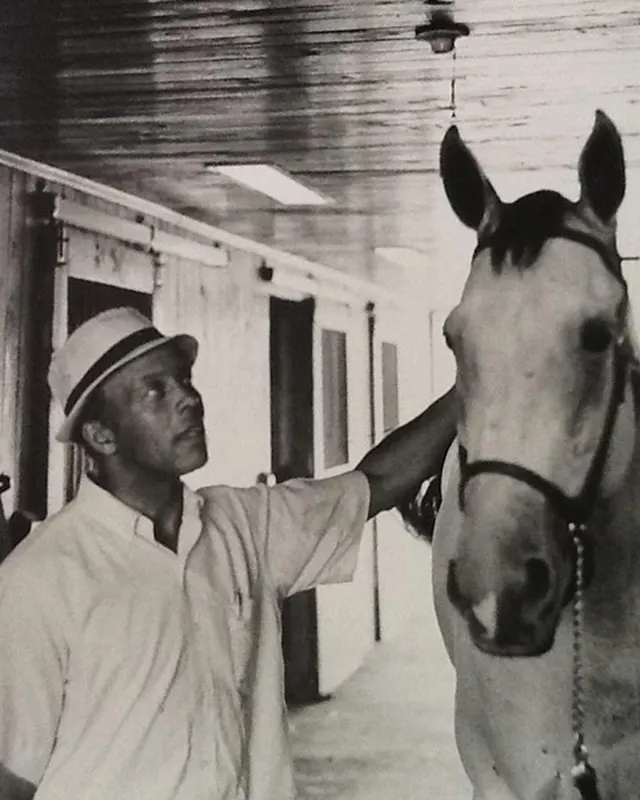

Sonny Brooks was a prominent show jumper in the ’50s and ’60s and is the only Black rider in the Show Jumping Hall Of Fame. Budd Photo

Brooks’ career was full of stories like that—of taking horses most would walk away from, but gently, patiently turning them into winners. Horses like The Hypnotist, who could barely hold a canter lead.

“That horse was crazy,” recalled Canadian jumper judge Phil Rozon, who befriended Brooks in the 1970s. “He’d be going down the line, and he’d be switching leads in the back and cross-cantering and doing everything, and Sonny would just take a tug, and he’d keep jumping him.”

Thorough And Meticulous

Brooks’ father, Charlie Brooks, managed the stable at Fairfield County Hunt Club, and the family lived in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Sonny, who started riding when he was 10, inherited his father’s natural touch, and he flourished under Charlie’s tutelage. But in the early ’60s, just as Sonny started to make a name for himself on the show circuit, Charlie died.

“Charlie knew that Sonny had it in him because he trained him,” Sells said. “He was the one who convinced the owners of the original stable Sonny rode for to put Sonny on the horse. And they took his word because Charlie was a pretty big deal in horse training. That was kind of a sad thing that he didn’t live to see his son become big.”

It wasn’t long before the esteemed Morton W. “Cappy” Smith noticed the young equestrian and invited him to ride at his farm in Middleburg, Virginia.

“Sonny was a very good rider,” recalled Olympian Kathy Kusner, who considered Sonny a friend. “He worked for different horse dealers and learned stuff from each one always. He was a basic horseman but a very thorough horseman.”

Following his stint with Smith, Sonny returned to New England, where he connected with another of Smith’s mentees, Bill Steinkraus. An amateur rider, Steinkraus split his time between a job in New York and riding for Arthur Nardin, and he needed someone to keep the horses legged up during the week. He chose Sonny for the task.

After Steinkraus was named to the Olympic team in 1952, he convinced Nardin to give Sonny a shot at competing the string of jumpers, including top horses Trader Bedford and Trader Horn.

Nardin was just the first on the impressive list of owners Sonny rode for throughout his career, including, but not limited to: Frank Imperatore, Bernie Mann, Jay Golding, Donald Shapiro and Norman Coates.

A Gentle, Systematic Approach

In 1953, Sonny broke a record at Piping Rock (New York), earning the most jumper wins in the show’s history aboard Ping Pong. The following year, he earned dozens of titles with Riviera Mann from places like Piping Rock, Fairfield, Ox Ridge (Connecticut), Boulder Brook (New York) and Oaks Hunt (New York). In 1961, he won his first National Horse Show (New York) open jumper championship on Imperatore’s Grey Aero, outriding the likes of Al Fiore on Riviera Wonder, Dave Kelley on Windsor Castle, and Harry deLeyer on Snowman. He repeated the feat in 1964 with Top Gallant.

“Horses really tried for him,” Rozon said. “Some people have that knack of getting horses to try harder for them, or the horses react to them in a different way.”

Sonny Brooks was known for getting the most out of his horses through his friendships and patience with them. Photo Courtesy Of Kevin Sells

In the ’50s and ’60s, there were only a few top trainers, so much of a rider’s education came from watching. Younger riders yearned to emulate Sonny, and he was generous with his knowledge.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dianne De Franceaux Grod met Sonny at the 1958 Washington International Horse Show (District of Columbia), when he came up to give her advice. Years later she worked for him in Florida.

“He was so wonderful to work for,” she recalled. “He was a friend, but he was also an idol. He was very generous with his time. That was a great time; I learned so much from Sonny, and I felt honored that he trusted me to ride his horses.

“He was compassionate, and he let the horses talk to him,” she added. “He read their minds. It was the horse first, and there’s no question about it.”

In the 1960s, Sonny moved to California for a brief period. Few were familiar with him before he pulled into Eaton Canyon Stables with a large rig and three top horses, but he quickly impressed.

“His performances, it was like riding a hunter in a hunter class; it was so smooth going over 5′-5’6″ fences,” recalled John Atkinson, who stabled next to Sonny at Eaton Canyon in Pasadena. “His hands were immaculate; he had the best hands of any rider I’d ever seen.”

Neal Shapiro, who would go on to win team silver and individual bronze at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, rode off and on with Sonny during his junior years. He remembers Sonny’s systematic approach to training.

“It was just good horsemanship and staying calm, being firm, and just having a really good, basic knowledge of a horse,” Neal said. “That’s what good horsemen do; they’re particular about the care of the horse and the equipment, and it just goes along with the training method—a systematic way of training horses, not just haphazard, helter-skelter. He had a system.

“He was terrific,” Neal added. “He was very calm, never got upset, never lost his temper, was just really straightforward. He would be somebody who would be a really good rider today. He was much more accomplished and polished than many of the other riders. He was very, very polished, and I think that came from his riding with Cappy Smith, that military-style background and very, very strong basics.”

Torn Between Career And Family

Riding often kept Sonny away from home, but when he’d return for family gatherings, it was always a reason for celebration.

“He was really good with kids,” said Sells. “All of us kids thought the world of Uncle Sonny. We knew if Nan was cooking jagacida [a Portuguese meal with red rice and lima beans] that Uncle Sonny wasn’t far behind because that was his favorite meal. We’d all end up sitting out on the second-floor porch late into the night.”

When Sonny arrived in Bridgeport, a trailer in tow, the youngest members of his extended family often got rides on the more gentle creatures.

“He was always very careful with us,” Sells said. “One of his big things he used to tell us was to never be afraid of the horse. Respect the horse, but never be afraid of it. I remember him telling one of his sons once that the reason he could ride so well was that he was friends with the horse. He said he wouldn’t get [half as much] out of them if he wasn’t friends with them.”

Occasionally, his wife Lucille “Ludy” Brooks and his sons Nicholas and Anthony joined him on the road—Nicholas had a great relationship with Kusner’s top mount Untouchable—but more often than not, he traveled alone.

But Sonny never lost his sense of community or his loyalty to his family.

“Sonny had a real heart on him,” Sells said. “You’d be surprised at how many people he’d come to Bridgeport and help out. There’d be neighbors that were on the downs. He never let any family have any major issues. If there was a family member that was out of work or something like that, he might speak to someone, or if it came down to it, he’d pay somebody’s rent.”

Racial Tensions

Sonny faced an uphill battle to gain recognition in an industry that primarily relegated Black people to grooming positions. His family believed his fair skin and light gray eyes contributed to his acceptance in the horse world.

ADVERTISEMENT

“My great-grandfather used to say that Sonny wasn’t offensive, so he was palatable,” said Sells. “And that certainly gave him a lot of opportunity to show off his talent. I think when it came to just pure talent, he stood on his own two feet. There was no question the other riders respected and looked up to him. I remember his reactions with fellow riders, and he was considered at least an equal if not a better with regards to the amount of respect they gave him because he just rode well.”

Though he won the biggest classes at many shows, he was excluded from the after-parties held at venues with whites-only policies.

“Sometimes the other riders would bring a few drinks and stuff to his hotel room where he’d be sitting by himself, and sometimes the other riders would try to bring the party to him, but that was more insulting than soothing,” Sells said. “I heard him say those words—it brought the pain closer. It pushed the knife in deeper.

“When he had his downtime, and he could be around his family, he’d speak his mind,” Sells continued. “He never uttered any hatred for anything or anybody, but it was a big disappointment.”

One year, President John F. Kennedy was slated to preside over an awards ceremony in New York City, where Sonny was to be honored, but due to his skin color, he was told he couldn’t attend.

“It was a very big deal among the family,” Sell recalled. “My great-grandmother, Sonny’s mother, spent a lot of time trying to get Sonny to understand that’s just the way things were. But Sonny, he wasn’t of that same mindset. He felt that he’d earned the recognition, and of course he had because he had a wonderful year that year.”

One of Sonny’s friends caught wind of the slight and through family connections got the word to Kennedy, who insisted Sonny be allowed to attend. Event organizers tried to stick Sonny off to the side by the kitchen doors, but Kennedy’s team gave him a spot at a table near the front.

Sonny Brooks earned his first National Horse Show (N.Y.) open jumper championship on Grey Aero (pictured) and repeated the feat in 1964 with Top Gallant. Carl Klein Photo

Throughout his career, Sonny never showed below the Mason-Dixon line, the one exception being Florida. Though most people were outwardly amicable on the showgrounds, finding places to stay was always a challenge, and harassment was common.

“He encouraged me to keep doing what I’m doing,” said Junior Johnson, who met Sonny when he was young. “He didn’t give up. No matter what hell he caught, he kept going. It was rough for him back in those days, really rough. That’s a tough thing, to [not] let something like that hold you back.”

Eventually, the racial tensions drove Sonny to Mexico and then Canada. There, Aubret Brilliant, the force behind the creation of the National School of Equitation, purchased three horses from Sonny: Grey Lady, Enterprise and The Hypnotist, and he engaged Sonny to keep competing them. According to Rozon, the combination of Sonny and the new equitation school helped elevate Canadian show jumping.

“Back in his day, to ride on the Olympic team, you had to be an amateur,” Rozon said. “He was always a professional because he earned his living from [horses]. But not having him on an Olympic team would be like not having McLain Ward on an Olympic team.”

On Feb. 6, 1976, Sonny died of a heart attack in Mexico, at the age of 54. In 2012, he became the first and is still the only Black equestrian to be inducted into the Show Jumping Hall of Fame.

“There’s nothing negative that you can say about the guy,” said Neal. “He was somebody that overcame a lot of obstacles of our time.”

He’s remembered for his tenacity, how he remained undaunted in the face of adversity, and as someone who laid the foundation for those behind him.

“[His advice to me was,] ‘Keep fighting and keep reaching forward,’ ” said Johnson, who is also Black. “That’s what kept me doing what I do today.”

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our February 8 & 15, 2021, Legends & Traditions Issue.

Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked. Or you can purchase a single issue or subscribe on a mobile device through our app The Chronicle of the Horse LLC.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.

What are you missing if you don’t subscribe?