In the early days of his career, legendary horseman Bill Steinkraus penned a regular column—Equitation and Horsemanship—for The Chronicle of the Horse under the pseudonym “Proctor Knott.” In this Throwback Thursday, we unearthed one of his Chronicle columns from the 1940s.

Published in the June 26, 1942, issue of The Chronicle of the Horse

One of the nice things about riding is that it affords pleasure at any age, whether one can ride a little or a lot. Fortunately, one does not need to have to own the wealth of Midas to sit on a horse’s back and benefit from the oft-quoted and sage advice of Oliver Wendell Holmes that “the best thing for the inside of a man is the outside of a horse.”

Sometimes children who promise to develop into lifelong riders go stale or suffer from too much pushing or parental pressure or some other cause and gradually drop out. Apparently that happens in other sports, too, and we were much interested in an article we happened to see on this subject in a recent issue of the magazine Golfing. The writer sets out to analyze why it is that so many brilliant possibilities among junior golfers fail to develop and fade out of the picture.

He comes to the conclusion that there are eight influences that control a young golfer’s future, in this order—”incentive, liking for practice, parental influence, natural ability, professional guidance, educational plans, intestinal fortitude, and finances.” Quite a practical list.

Immediately we thought of horses. What is it that controls the progress of a young rider? Why does one excel, another remain average, another poor? We would put first, by all odds, ability. That is the great determining factor in the long run. A horseman must understand his “genus equus” and have a feel for a horse. The Irish, bless them, seem to be born with it! A real horseman has a sensitivity towards horses and can almost tell you how his mare is feeling before he is on her back, as much as if he asked, “How do you feel today, old girl?”

This native ability with horses is a complex thing, far more difficult than learning a set of swimming rules, or knowing the laws that govern the curve of a golf ball, for with horses you are dealing with a variable factor, and no two horses ever breathed who were just alike. Anyone who rides mechanically by rule will turn out to be a stupid poor rider.

We are old fashioned enough to believe that riding ability is usually inherited, and in the background of every young rider is some horseman of the past. Fortunate indeed are those who come from riding families! In the case of others, it is amazing what polish a Frank Carroll or an Annie Lawson can put on even a mediocre rider, but there comes a point where actual ability must count, and the best teacher cannot do a thing more.

ADVERTISEMENT

Most jockeys have great native ability plus what they have picked up along the way. Think of Donaghue, the greatest, and our own Arcaro, Meade and a host of others—real born riders, playing at about the toughest game there is. Meade’s sheer ability has swept him along where personal mistakes would have sunk a less gifted rider.

“Incentive” and “liking for practice” we would next place in importance, but would prefer to call it simply “just liking to ride.” If a child likes to ride, you don’t have to worry about his not practicing. He would rather ride than sleep, eat or drink, and he will gladly crawl out of bed at 4 o’clock in the morning to hack to a hunt. He will try to conceal the fact that he has a fever of 102 if it means he may lose a ride; he doesn’t cook up excuses. Well, that is riding—either you love it or you don’t, and what a shame it is to urge and push a child who doesn’t like it.

Thirdly, we would put “professional guidance.” Frequently before in these columns we have tried to stress the advantage of taking lessons as early as possible under a good instructor as the quickest and safest way to learn to ride. In advanced horsemanship it is even more important.

Stick-to-it-iveness, or keeping at a thing is of course a great factor in any sport—or as the golfer calls it, “intestinal fortitude.” That covers, too, the taking of criticism, without which no one can excel in any sport. It is hard to criticize, and if anyone older and wiser is willing to offer criticism, it should be accepted gratefully.

“Parental guidance,” which the golfer rates as a strong factor, we would be inclined to feel is overdone in riding, especially at meets and classes in horse shows. The child who is on his own will learn much more in the long run and will learn far more valuable lessons than the child who has his parents handy to overcome every difficulty that arises.

Parents as a class tend to make children nervous, and they take the minor injustices that cannot help but accompany shows much too seriously. Have you ever noticed how well judges and children get along together, with mutual friendliness and understanding, and then parents will step in and spoil it? That is not meant to sound harsh, but we can think of actual instances.

Educational plans can interfere with progress in riding, as in other sports. In going off to “prep” school the interruption of nine months without riding sets a child back so that he never thoroughly gets caught up. Like golfing or swimming, riding cannot be dropped entirely in a formative stage without loss. Unfortunately, schools like those in Greenwich, Connecticut, and several through Virginia and Maryland, that give credit for riding are the exception.

Lastly, we come to “finances.” Riding is expensive, and there isn’t much you can do about that. There is no benevolent American Athletic Association or local Athletic Club to finance the talented novice, he must meet his own expenses. In Europe, where equitation is more honored, there are such ways and means, but it is a fact that under our system many gifted riders cannot afford the training they ought to have.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many children drop out of showing because making the circuit is so expensive for their parents, in some cases, expensive beyond all reason. Actually it should not be necessary to go to anything like the number of competitions children now feel they have to go to. It is not the number of blue ribbons, but meeting fair competition that benefits the rider and establishes his position. At too many shows of recent years the horsemanship classes virtually repeat themselves. Some process of elimination would be much saner, such as that sponsored by the Tennis Association matches.

Well, there it is! There is no short and easy route.

If we had only one wish for boys and girls it would be the wish that every child who loves a horse and wants to ride, could ride, and that no one would be pushed and made to ride who didn’t really want to.

Read more of Steinkraus’ writings for the Chronicle as Proctor Knott.

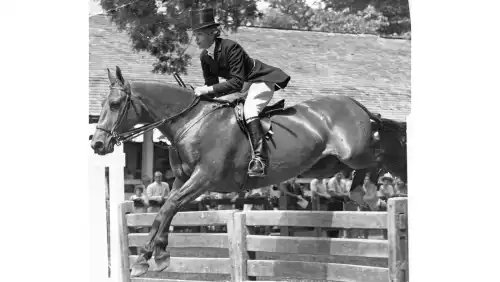

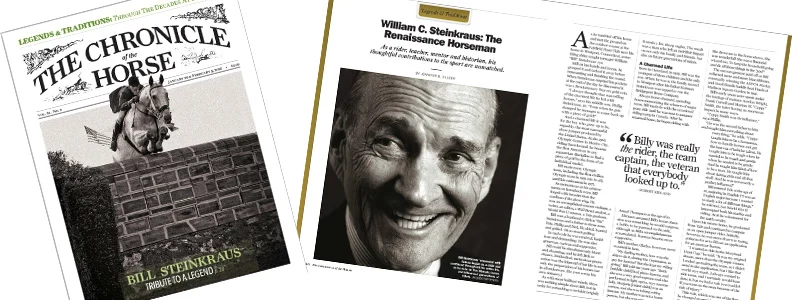

William C. “Bill” Steinkraus, the first U.S. show jumper to win an individual Olympic gold medal, died on Nov. 29 at the age of 92. The Chronicle published a tribute to him in the Jan. 29 & Feb. 5, 2018, Living Legends Issue of The Chronicle of the Horse.

William C. “Bill” Steinkraus, the first U.S. show jumper to win an individual Olympic gold medal, died on Nov. 29 at the age of 92. The Chronicle published a tribute to him in the Jan. 29 & Feb. 5, 2018, Living Legends Issue of The Chronicle of the Horse.

Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked. Or you can purchase a single issue or subscribe on a mobile device through our app The Chronicle of the Horse LLC.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.

What are you missing if you don’t subscribe?