In the late 1960s and early 1970s a memorable Appaloosa gelding named Crocodile turned heads on the West Coast show jumping circuit. But for his rider, the late Twinkie Nissen, some of his biggest accomplishments weren’t over colored poles at all.

Born Dorothy Watson, as a young child Nissen told her father, William Harris Watson, that she “wasn’t going to answer to that”—an early sign of her stubborn and strong-willed nature. She would go by Twinkie, the nickname her father gave her, for the rest of her life.

She was introduced to riding as a child at her all-girls school. The school’s six horse-crazy pupils shared the same mount, and she quickly grew to love the sport.

As an adult, she married veterinarian William “Bill” Nissen, who became her biggest supporter and regular show groom as they traveled the West Coast show circuit.

Making A Name For Himself

In the mid ’60s, husband and wife drove from California to Louisiana to horse shop. That’s where they purchased the 1964 Appaloosa gelding (Burnsides Chief Of The Pampas—Desert Lepor-E, Geronimo Chief), who was registered as Rose Ridge Dynamite but was called “Rosebud” around the barn. His new show name, Crocodile, came from both his Louisiana heritage and the mottling around his eyes that reminded Bill of the reptile.

“I think they bought him for about $25,” said Blair Nissen Pettit, Bill’s daughter from his first marriage, and Twinkie’s stepdaughter. “I’m pretty sure he was set to ship out on a hamburger truck when Dad and Twinkie found him.”

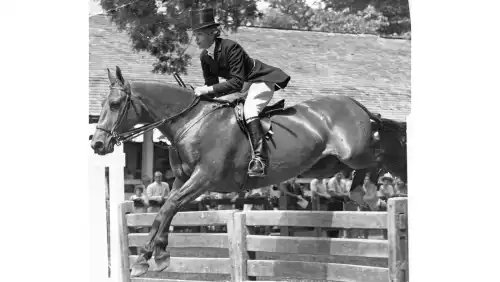

Twinkie was tiny, but Crocodile was huge—nearly 18 hands—with a blanket of spots on his hindquarters and scraggly tail, making the pair quite distinct.

Crocodile was also a total ham.

“He nickered every time he entered the arena, and he’d look around like he owned the place,” Pettit said. “People loved him. He was a crowd favorite. They always got the loudest cheers when they came into any arena.”

In fact, Corby Nissen, Pettit’s sister and Bill’s eldest daughter, recalled how, as an advertising tactic, the Cow Palace near San Francisco would measure the volume of applause of its different acts and events like a modern “applause meter” at professional sporting events. During the years he competed, and even into his retirement, Crocodile held the highest applause rating of any event in the venue.

Twinkie and Crocodile cleared their first 6’ fence at Indio, California, in 1969, their first year showing. Corby remembers a particular puissance, in particular, when Crocodile was young.

“He cleared the jump,” she said. “But Twinkie refused to move him to the next round, when the jump would be raised. She felt really strongly that he’d had enough that day, and she didn’t want to push him too hard, or risk breaking his spirit.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Her mindset of putting her horse’s wellbeing first paid off. Twinkie and Crocodile competed—and won—all over the West Coast in the late 1960s and well into the 1970s, and Twinkie trusted him enough to compete him even when she was seven months pregnant.

The pair earned the “B” jumper championship in the Pacific Coast Hunter Jumper And Stock Horse Association circuit in 1971, having earned the reserve title the year before. Crocodile cleared 6’9” at Indio, California, in February 1972 to win the knock down and out jumper stake, among the many jumper stakes wins of his career. An image of Crocodile graced the cover of the September 1976 issue of the California Horse Review.

“Twinkie and Crocodile showed all over, from Indio to Santa Barbara, and all down the coast,” Pettit said. “The Cow Palace was really cool in the evenings. They’d have a Saddlebred class, then show jumpers, then the rodeo. It was definitely a spectator thing. And when Twinkie and Crocodile would go in to do the high jumper or puissance, the crowd would just about tear down the house.”

At the end of his career Crocodile retired at a ceremony held at the Cow Palace. He moved to Bill and Twinkie’s ranch where he lived out his days, surrounded by the family’s other big-name show jumping retirees and a pony that belonged to the late Wendy Nissen, Bill and Twinkie’s only child together.

“Twinkie and Dad kept their horses for the rest of their lives,” Pettit said, “so it was quite the crew.”

A Higher Calling

Beyond his prowess in the jumper ring, Crocodile was a family treasure.

“Crocodile was the most gentle horse in the world,” Corby remembered. “I think he was just hatched that way.”

“And he was just the sweetest to Wendy,” added Pettit.

Their sister Wendy was born with the genetic condition Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, a severe type of progressive spinal muscular atrophy. With extremely weak muscles and a limited use of her limbs and torso, she was labeled a quadriplegic by doctors.

Corby said that Twinkie was “absolutely devoted” to her only child, who was not expected to live beyond the age of 2. Wendy died just before her 33rd birthday, a fact that Corby credits to the excellent care from both Bill and Twinkie, and the way they both advocated for her.

“When Wendy went in for her first surgery as a little girl,” Corby said, “Twinkie promised Wendy that she’d never spend the night in a hospital alone.”

Twinkie held to her word for more than three decades, even during Wendy’s longest hospital stay: six weeks in the ICU on a ventilator. Twinkie spent every night with her daughter, only leaving Wendy’s room to eat rushed lunches and dinners with her husband.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The thing I loved most about Twinkie,” Corby said, “was the way that she loved my sister.”

Wendy caught the horse bug early on, and Twinkie and Bill had a special saddle made for her with a high, supportive back. As a young child, she’d ride Crocodile in leadline classes at various horse shows before her mother would compete him in the big jumper events in the evenings. The horse was special, Corby said: He knew that Wendy needed him to be steady and calm, and he always was.

Crocodile influenced all of Bill’s children in various ways. In elementary school, Bill’s daughter and Twinkie’s stepdaughter Karine Nissen wrote and illustrated a children’s book about Crocodile. Big sister Corby encouraged her to edit it, then helped usher it to publication. The message is simple and sweet: Crocodile, embarrassed about his skinny tail, wants a big tail like the other horses. But he comes to learn that he is perfect just how he is. Corby and Karine dedicated the book to their sister Wendy.

Crocodile died on the family farm, well into his 20s.

While Crocodile was the top jumper of her career, Twinkie continued to compete in amateur-owner hunters into her 70s, always with Bill by her side helping prepare both her and her mount, and often supported by her daughter and stepdaughters as well. During her long career, Twinkie suffered several debilitating accidents and injuries, but, according to Corby, “She’d just wait for them to heal up, then get right back on.”

“She just always had an excellent eye,” Corby said. “Even after recovering from her injuries, including broken legs, that really hindered her strength and flexibility, it was her eye that kept her as competitive as she was.”

“I think people were glad when she finally quit competing,” Pettit said with a laugh. “She was always winning. She was tough as nails, even at the end of her career.”

Bill died in 2008 and Twinkie in August 2021, cared for by Bill’s daughters. The family’s equine legacy lives on: Corby and sister Lindsay Nissen Irby live on the family’s Sheridan Ranch in Sheridan, California, where Irby runs a boarding, training and lesson program, and Pettit works at a show secretary for outfits like Blenheim EquiSports, Desert International Horse Park and the Pennsylvania National.

“Crocodile was a chill guy,” Irby recalled. “At home, I’d climb the fence and lay across his back, and he’d just hang out there. But when he went into the arena, he took on a whole different persona. There will never be another horse quite like him.”

Corby agreed.

“That horse just had a huge heart,” she said.