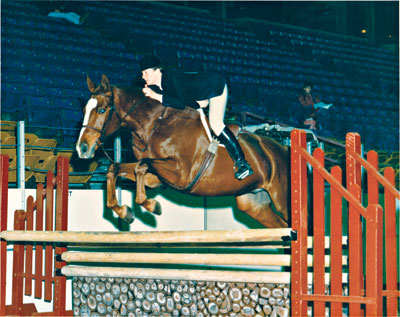

Susan “Tutti” Skaar, of Bozeman, Mont.

This isn’t necessarily your typical story of a horse’s death, but it truly is indicative of remote ranch living and figuring out solutions when help isn’t readily available.

This isn’t necessarily your typical story of a horse’s death, but it truly is indicative of remote ranch living and figuring out solutions when help isn’t readily available.

The accident with Sporty, a 16-year-old Quarter Horse we used for mountain trail riding, occurred in October 2002. That night, my husband Gary and I had just gone to bed, having been driven inside earlier in the evening by extremely strong winds, which continued to howl.

Suddenly we heard a very unusual noise in the pasture. Gary looked out the window and noticed our horses galloping around in frightful chaos. When Gary looked more closely, he realized one of the large lean-tos had blown over and was on its roof. He ran outside to investigate. I got dressed and headed out, but Gary yelled: “Stay inside! Sporty is hurt.”

I didn’t follow instructions and went closer, only to find that the lean-to had landed on Sporty’s head, which was trapped underneath this large, very heavy wooden structure. Sporty’s legs were moving as if he was trying to get up, but he was hopelessly pinned.

Gary made the difficult but appropriate decision to put Sporty down. He told me to go inside and get his gun. There wasn’t time to call for help; it would have taken at least an hour for a vet to get out to our place, and the horse would have suffered. I delivered the gun, and Gary insisted I go inside–which I willingly did. He shot Sporty in the head, killing him with one bullet. I was crying the whole time.

The wind was still blowing, and Gary needed help. He used a jack to lift the lean-to off Sporty, got a rope and dragged him out of the pasture–using the truck to pull him. We had to get Sporty away from the other two horses. The wind was still blowing fiercely during all of this.

When dawn broke and we went out to look at the situation in daylight, we could see that the lean-to had hit Sporty in the back first, then pinned him down on his head. I’m sure he had a broken spine. We contacted a neighbor who is an excavator and he dug a hole to bury him on our property. We spent the next two days breaking down the lean-to piece by piece, salvaging what parts we could.

We went through a whole range of emotions—shock, fear, panic, disbelief and sadness. It helped that we received lots of sympathy cards. I didn’t take time off from work when Sporty died, but I took time off when my other horse Willy died of colic and when our dog died last summer.

ADVERTISEMENT

I kept a lock of Sporty’s mane. We didn’t mark his grave, but we know where it is. We have three dogs, one cat and one horse buried on our property.

Looking back, I’m glad that we were able to immediately put Sporty out of his misery. And now I always tell people that their lean-tos must be well secured in the ground, with posts dug at least six feet down. The manufacturers don’t suggest this, but we’ve seen too many flip over. The chances of a lean-to blowing over and injuring a horse are probably one in a million, but it happened to us.

What I learned from this experience is that I need to know how to put a horse down. When we do mountain trail rides, there are many instances where we might have to put a horse down. This summer I’m going on a pack trip in a wilderness area with six women friends. We’ve already discussed who was going to bring a gun, and why it is so important to have one available.

Nancy Sutherland, of Olathe, Kan.

My family has lived on a horse farm near Kansas City for many years, and in that time I’ve had to deal with the death of three retired Thoroughbreds, all under different circumstances. [Eliza, 25, and Pantano, 22, both former show hunters; and Hot Jaws, 18, a former race horse.]

I’ve never really had an arrangement worked out with my veterinarian for when my horses might be dying or dead, but I’ve always tried to have a general knowledge of all the options available, since I own horses and know that dealing with death is pretty much a certainty.

With Eliza, I decided it was time to put her down in 1994 because of quality-of-life issues. Her age was making her life difficult, and she had started losing weight pretty rapidly. I think it’s a positive thing that we can end an animal’s suffering, so it doesn’t experience undue pain and stress.

First, I called the rendering company to see when they could schedule a pick-up, then I made the vet appointment for the same day. You don’t want the animal lying on your property for an extended period of time, because of decay–and the body will attract predator animals.

I was so sad; Eliza was such a wonderful horse. It’s such a long process when they’re old and you evaluate them on a day-to-day basis. Knowing and deciding when the time is right is torture. There’s probably more emotion leading up to the decision when it is pending. Then, of course, it’s extremely sad to finalize the plans and proceed. It makes me sad to think of Eliza, even to this day. But she had lived a nice long life.

ADVERTISEMENT

Pantano died in the pasture in 2001, during the night. I went out for morning chores and saw him lying down, but I immediately knew that he didn’t look right; in fact, I sensed right away that he was probably dead. The night before, he had been happily eating at a round bale.

I called my trainer, Mike McCormick, to share the bad news. Pantano was the first horse I had when I started riding with Mike. My kids had also ridden him after he retired as a show horse, so the whole family was quite sad.

But like Eliza, Pantano had lived a nice long life and had a great retirement on the farm. I reminisced about what a great horse he had been, but I was satisfied that his life had been a good one. We buried him on the farm, in an unmarked grave.

In the case of Hot Jaws, last year I took him to the vet with an impaction and stayed for the initial examination. Hot Jaws wasn’t in distress at that point, and the vet and I discussed options–including possible surgery. I left the clinic thinking I had about 24 hours to decide what path to take, depending on the horse’s progress or lack thereof.

Within an hour of my leaving the clinic, the vet called and said that Hot Jaws needed to be euthanized now because of the immediate onset of sepsis from a tear in his colon. I thought: “This cannot be happening! How can we save him?” It was horrible, and it all happened so fast. I was in complete shock. I wanted time to say my goodbyes, and to absorb what was going to happen.

My family and friends knew Hot Jaws was sick and at the vet, but he had to be euthanized so fast that there was no time to think about the decision to put him down, or to talk to anyone about it before it happened. Fortunately, I had lots of support from everyone. Horse people are always sympathetic!

I didn’t choose to have Hot Jaws put down at my farm and buried there. Since he was at the vet clinic, the logistics of getting him back to the farm would have been difficult. I didn’t want to load him in the trailer one more time just to have him put down at home. I thought that would have been too cruel to do to him solely for my own satisfaction. I didn’t ask the vet what they did with Hot Jaws’ body; I was too upset. But it probably went to the

renderers.

I’m comfortable with the decisions I made for all three horses. I’ve kept all of their halter plates, which hang on a wall in my barn. During these experiences, I learned that each animal’s death is unique and equally hard to deal with. If you have horses at home, hopefully you’ve given this subject some thought. There are some pretty standard ways of dealing with animal removal, and there are more options available now than ever before that involve individual cremation, or burial in a pet cemetery.

Your veterinarian can be a great resource for options. If you learn about the various processes ahead of time, it might be a tad less stressful. Owning horses involves many responsibilities. Unfortunately, dealing with their death is one of them.

As told to Anne Lang