In this article, the third in my series on the future of the horse industry (click to read financial planning and business management strategies), let’s tackle boarding. This is an issue that should be of interest to almost all of us. Even if you are not a professional, you probably need boarding barns to be functional, financially healthy businesses. If boarding barns around the country close or sell due to financial strain (which is happening in greater numbers every year), where will people keep their horses? Who will host local, affordable shows?

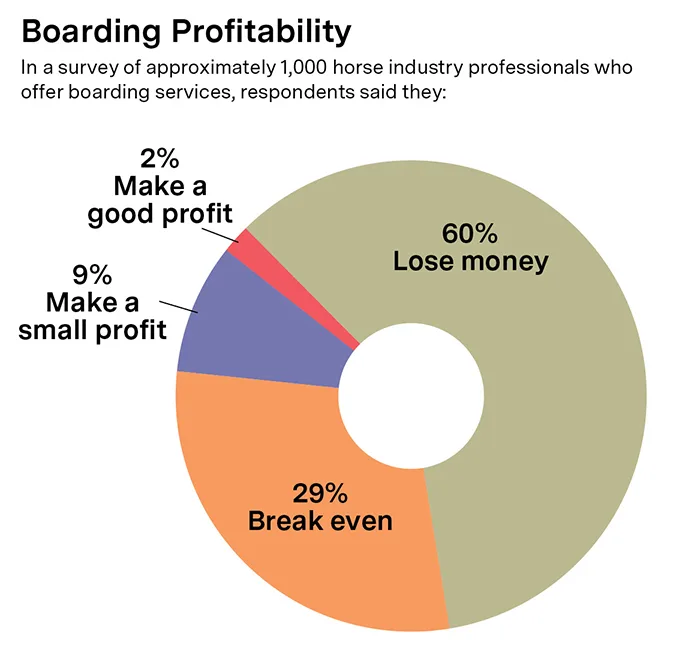

When I surveyed over 1,500 horse professionals last year, 66% of respondents offered boarding in some capacity. Of those people, a full 60% lost money each month on boarding, 29% broke even on each horse they boarded, 9% felt they made a small profit on each horse, and only 2% of respondents reported making a “good profit” on each boarded horse.

I want to acknowledge that for many barn owners, they are not even trying to make a profit. Either they just want boarded horses to pay for their own horse’s expenses, or maybe they are utilizing the loss on their farm business to reduce their overall tax burden, or maybe they’re just incredibly nice people who don’t mind losing money. If this describes you or your barn owner, and the situation is working well for all of you, keep at it!

But for many, many barn owners, losing money each month or maybe breaking even (after also working your tail off) is not a sustainable situation. Even a wealthy, benevolent farm owner will sooner or later say, “Wait, why am I paying for other people’s horses each month?!” And when they inevitably get tired of the trifecta of financial, physical and mental strain, they often kick all their boarders out or put their farm up for sale. If you are a conscientious barn owner who is losing money each month, why not get rid of all the boarders and lose money each month on your own few horses, with no stress in your life? I’ve heard some version of this story over and over again. And the loss of rural farmland is getting worse each year, so in order for owners to continue to operate, we must crack this problem.

The horse industry suffers mightily from what economists call the “passion tax”: You love horses so much you’re willing to operate at a loss, just to stay in business. And I believe this is where our horse professional community needs to come together to support each other. If everyone in the market is undercharging because they’re subsidizing their business with outside income, it creates a race to the bottom. Young professionals think that’s what boarding should cost, and the cycle continues.

Let’s look at the problem more in depth and also look at some examples of people making it work.

The True Cost Of Boarding

So often I heard from struggling barn owners, “I made a spreadsheet of expenses when we started, but I just had no idea of the true costs!” So what are they? You’ve got your fixed costs (some operations will have other, but these are pretty standard across farms):

- Mortgage or rent payments

- Property taxes

- Insurance (liability, property, workers’ compensation)

- Utilities (water, electricity, waste management)

- Regular facility maintenance

Then you’ve got your variable costs that fluctuate based upon the number of horses or time of year, such as:

- Feed (hay, grain, supplement)

- Bedding materials

- Labor (staff salaries and benefits)

- Equipment maintenance and replacement

- Marketing and administrative costs

- Supplies (which can cover anything from laundry detergent to new wheelbarrows to fence boards)

Again, many operations will have others, and it is vital that you take the time to recognize all of them.

“It can’t cost that much to buy hay, shavings, and grain,” is a complaint I hear from boarders when the farm owner raises the board price. So let’s think through how you come up with a price for board. A simple formula for calculating what you should charge each horse is:

- Calculate total monthly operating costs

- Add 10-15% for contingencies and profit

- Divide by the number of stalls

- Add a margin for vacant stalls (usually 10-15%)

In many operations, it is hard to separate out what expenses are “board only” versus “training or lessons only.” The formula above is simple and should be adjusted to each business.

Charge What You Are Worth

Let’s call this Option A for fixing the boarding business problem: Business owners simply need to charge more.

Ana DiGironimo, who runs DQ Performance Horses, in Swedesboro, New Jersey, took exactly this approach. “If I didn’t make a change, I would have gone out of business,” she told me. “It was not an option anymore. It had to happen. I knew there would be pushback and questions, and I was very ready to answer them, to provide plenty of information for my clients on what it really costs.”

Because she has owned her own farm for about six years and leased a place for five years before that, Ana had a very good understanding of her expenses, and she knew exactly how she wanted to run her barn. “I wasn’t changing my standards. I don’t want to manage in a different way.” She also researched similar barns and training programs, both locally and outside of her region, to find out what comparable prices looked like. “I was pricing myself well below industry standards. This not only justified adjusting my rates to better reflect the value we provide, but also underscored what clients should expect to invest in high quality service.”

Ana kept a spreadsheet that tracked every single expense: eye hooks, brooms, grain, hay, tractor maintenance, seeding, laundry pods, etc. “My primary cost is staff,” she said. “You have to pay them well and offer a competitive package.” This is true for the vast majority of barns, as the labor component alone often consumes 40-60% of an operating budget.

Once Ana had a totally clear picture of her average monthly expenses, she calculated what she would need to charge. The care in her barn is very individualized. All private turnout with three shifts offered (small, mid-day and all-day turnout). Boots, blankets, fly spray, laundry service, and handwalking are all included. The care of the horses is paramount. They feed four meals a day, pretty much free choice hay, and fields are picked weekly.

Her old board price was $950 per month, and she was bleeding money.

“I have a wonderful group of clients, who I love and appreciate and who have supported me for so long. I knew if I didn’t do this, I was only hurting myself. I work 14 hours/day, 5-6 days a week,” she said. So she bit the bullet and raised board by $500, making it $1,450 for “premier board,” minus grooming services, and $1,800 for full care, which includes grooming and tacking, preparation for shows, scheduling for vet and farrier, etc.

ADVERTISEMENT

Even at this price, Ana is still losing approximately $200 per horse per month. She makes a profit in other areas of her business, such as training, lessons and sales, so she felt like losing $200-250 per horse per month was reasonable. “I think of it as the cost of doing business. I’m willing to absorb a little to run my program successfully, but it has to be sustainable.”

Option A is purely business-driven: Figure out your expenses and charge enough to cover them and give you a small profit. Pretty simple. Simple, but not easy, and in many parts of the country, not even realistic. So what are the other options?

Increase Efficiency, Decrease Labor

Option B is going to require that barn owners assess how the horses live, what can be more efficient, and how to get by with less labor. The answer here is how to get by with less (wo)man power. As I combed the data from my survey, it became clear that the most profitable operations have a shockingly low ratio of employees to number of horses. As I talked to folks, this was reiterated, either because they cannot afford or cannot find reliable workers.

The big question is, what are you spending the most time and/or money on, and must you do it that way? If the biggest labor need is cleaning stalls every day, can the horses live out more? In some parts of the country, it’s not an option due to weather or lack of land. But in my own experience it’s more often the unwillingness of the barn owner or horse owners to change their mindset. Almost every vet will tell you it’s better for horses’ health to be out, with other horses, as close to 24/7 as possible. It’s also the cheapest way to keep them. If you’re unwilling to make that change, that is your choice. Just be honest if it’s more about your fear or about keeping up with what other “fancy barns” do than it is about running a financially solid business and taking excellent care of horses.

Brooke Griffin runs a large boarding operation out of Don E Mor in Siler City, North Carolina. Don E Mor sits on 170 acres, with a covered arena, outdoor arena, 22 stalls, beautiful grass pastures of varying sizes, small dry lots and 8 miles of trails. A gorgeous farm like this can charge whatever its owners want, right? Except, Siler City is a far cry from Middleburg, Virginia, or Wellington, Florida. Boarders in this rural part of North Carolina are simply unable, for the most part, to pay huge prices.

Brooke keeps an average of 40 horses on the farm. There are two other full-time employees, one of whom lives in the apartment in the barn, and two part-time workers. Brooke is not a trainer, and running the barn is her sole income, so she has to be very clear about what works and what doesn’t. “If you’re going to board horses, it’s so much easier to have a pasture board option, and dry lots make for less labor,” she said.

One upside to this facility is its size and the excellent grass. Each field has a run-in shed, and horses are kept in small groups, for the most part. Brooke readily admits that Don E Mor is an exceptional facility to lease.

“The equipment—tractors, Kubotas—and diesel is included. I pay a flat fee for the whole facility,” she said. “The only extra each month is electricity. The owners are wonderful. They live on the farm and jump in to help out when needed.”

Efficiency is a key word for her: She buys supplies, including diesel, in bulk, and the facility is designed with efficiency in mind.

“If there’s a job I can do, and I don’t need a staff member to do it, then I do it,” she said.

Many of the fields have automatic waterers, and although they still use water buckets in each stall, there is a spigot in every stall, so there’s no need to pull a hose around to fill each bucket. A fly spray system throughout the barn cuts down on time spent dealing with flies.

While the upfront cost of installing automatic waterers, or a fly spray system is high, the savings in labor can be huge. When I ran my own barn, my workers were spending about 45 minutes each day dumping buckets, scrubbing every one in the wash stall, putting them back and then refilling them. I worked with the owner of the facility to split the cost of installing automatic waterers. It paid for itself within two months, due to the reduction in labor.

Another efficiency question for most barns is manure management. People don’t want the manure pile right next to the barn, because it’s gross and stinky and attracts flies. But too far away is a huge waste of time for your stall cleaners. Is it best to do it the old fashioned way with wheelbarrows or muck buckets, or is a manure spreader pulled through the barn the best? Is composting the manure onsite the way you want to go, or having a dumpster and hauling it away each month? All options must be weighed for time efficiency, cost and ease of operations.

The same goes for turn out: If every horse gets private turn out, and the paddocks are far from the barn, that’s going to take a ton of time. If you have the luxury of designing a facility from the get go, these are the biggest things to think about, even though they are not as fun as making a pretty looking barn. What design features help you to save time and/or money?

Brooke tries to say yes to requests from her boarders (within reason), but she communicates clearly on prices.

“Everyone gets a price list, and if it’s not on the price list, we talk about it ahead of time,” she said. “Client problems are not my problems, and I’m a stickler for the extras.”

If a horse needs something that requires extra labor—wrapping at night, paste medications, getting them from the field because the owner is running late for their lesson—the owner expects to pay for these. Brooke uses an app called Invoice2Go, so that as she goes around each day, she can easily add things to a client’s invoice directly from her phone, so it doesn’t get lost in the busy-ness of the day. Brooke wants to do everything she can to keep her equine charges and their owners happy, but it has to make financial sense.

“I’m much more willing to get rid of bad clients quickly; it’s not worth my sanity. Clients are paying for my knowledge, paying for their ability to go on vacation and not think twice, paying for someone to be on site 24 hours a day.”

Brooke Griffin

“I’m much more willing to get rid of bad clients quickly; it’s not worth my sanity,” she said. “Clients are paying for my knowledge, paying for their ability to go on vacation and not think twice, paying for someone to be on site 24 hours a day. I have to plan a vacation a year in advance! If they don’t appreciate all that, they don’t last long.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Brooke’s good management means that she runs a profitable business, and while she certainly doesn’t live an extravagant lifestyle, she is happy with things. “With my solid and loyal employees, I have the ability to leave the farm, have regular vacations, and schedule normal days off and family time for myself without it being a financial burden,” she said.

Time To Get Creative

Option C is to think outside the box (or stall!) and expand your idea of how a barn might be run. Let’s say you don’t own any land, you can’t afford to buy or lease a place, and you can’t afford to board at a top boarding barn in your area. Do you have to just get out of horses? No! We need other models that welcome everyone, not one model that is getting increasingly expensive and out of reach for so many.

Lots of people have figured out how to make co-op barns work over the years. Someone owns a nice facility, they’re happy to have people there, but they don’t want the headache of managing it. Usually a co-op model can only work with a smaller number of people.

Carol Cunefare in Durango, Colorado, helps to make her co-op barn run smoothly. “We have 10 horses, max,” she told me. “The camaraderie and family atmosphere is most important, supporting one another and participating in clinics and shows together!”

Carol said it was hard to find good boarding options in her area. When the owner of her facility built it, she did not want the headache of running the whole thing herself. So each boarder has a base price of $750, which includes a stall and attached run, access to a big indoor that is kept watered and dragged, and hay and grain twice daily. No cleaning is included, and everyone is responsible for providing their own shavings and any special hay or grain. Everyone must pick up shifts to help with chores. If someone cannot cover a shift for chores, outside help is hired or another boarder picks up extra shifts, and the cost is split among those unable to help.

Duties in Carol’s barn are very clearly outlined, and the spirit of community is strong. Everyone must pitch in on tasks such as sweeping, mopping, cleaning the bathroom, picking pastures, etc. Boarders have a signup sheet to keep it organized, and when tasks are completed, they sign off with their initials. This method may not work for everyone, but if you have a strong group of friends who all want to keep costs down and care for their horses in a similar way, it can be a fabulous option!

Complete self-care is another option I hear more and more about. Boarders pay for a dry stall and access to the facility, and everything else is on them: bedding, hay, grain, feeding, turn out, etc.

Are there other models out there? Absolutely! Barn management is not one size fits all.

Communication Is Key

Underlying all these options is excellent communication. Barn owners must be honest with themselves and their clients and communicate clearly what is needed to continue to operate and what is expected for success in each barn.

Susie Greene owns Remington Run Stables in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. An adult amateur, she had boarded at many barns and always dreamed of having her own. As a strategy consultant and university professor of entrepreneurship, she brought a practical mindset—and a clear-eyed plan—to making that dream a reality.

“We took the time to make our boarding agreement really specific and took the time to interview potential boarders, talking about the elements of the agreement, how the operation works, who is responsible for what, what will and won’t be charged, how unexpected things will be dealt with, etc.” Susie said. “This can make a huge difference in alleviating misalignment in expectations down the line.”

Before building her beautiful barn, Susie did a ton of research on facility design and management. She looked at many, many boarding agreements, and noticed most of them focused on liability issues and pricing but didn’t outline many other important things. “With each new boarder that comes in, we go back and update the agreement based on what we have learned and what has changed.”

Take the time to find clarity on exactly what you want in your barn as either an owner or a client: Do you want to be in a barn full of kids or not? Do you want to be in a serious, competitive environment or not? Do you want to be a hands off boarder or have a very community focused barn where everyone pitches in? These things need to be outlined in your agreement.

“Don’t avoid the hard conversations,” Susie said. “Challenges and concerns are a natural part of any business, and it is essential to address them directly rather than avoid difficult conversations. To prevent tensions from escalating, respond to issues as they arise, maintain a professional tone, and refer back to the boarding agreement as a shared point of alignment.”

Transparency and communication make for a successful operation where both the owner and the clients feel seen and heard.

“It’s OK to make it clear to the boarders that the operation needs to be profitable, even if only slightly, if we all want to continue,” Susie said. “Maybe let clients know in your agreement that board will increase by ‘X’ dollars every 6 or 12 months, unless costs magically decrease, or you get to a break-even or profit goal.”

I’ve always heard, “You can’t make any money in boarding!” While the results of my survey confirm that to be true for most people, it’s still a strange thing for us professionals to just resign ourselves to. I don’t think most other industries would say “Oh well, this huge area of our business loses tons of money, guess we’ll just keep doing it this way.”

We must see a better future that is sustainable for both clients and business owners. If you have ideas on ways to run a boarding barn that have worked well for you, or any questions I could possibly help with, please feel free to comment on this article or reach out to me on social media.

Eliza Sydnor Romm is an FEI rider and trainer from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She is a USDF Certified Instructor and sought-after trainer and clinician. She teaches horses and riders of all levels, from starting under saddle to Grand Prix.