In the January 17, 1997 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse, a Between Rounds column by Denny Emerson looked at five great riders’ “once in a lifetime” horses.

What red-blooded young rider hasn’t dreamed of someday riding a true wonder horse? Who hasn’t wanted to ride a horse of such power and scope and courage that he could trust that horse with his very life?

For a select few riders, this dream has come true. An even smaller number of riders have ridden several of these “once-in-a-lifetime” horses, so that they’re in the position of being able to choose which of several great horses was ultimately the most reliable.

The idea behind writing this article actually originated 35 years ago when I read the following caption beneath a photo of William Steinkraus riding Ksar D’Esprit in his book Riding and Jumping.

Steinkraus wrote: “ ‘Ksarro’ has his personal idiosyncrasies, and the fact that he sometimes finds small fences boring is one of them. How grateful I have been to him for knowing just what to do with the big ones, however! In the picture above he is taking me quite unconcernedly over the biggest fence I had ever ridden up to that time, Rotterdam’s puissance wall set at just over seven feet. Since then Ksar has taken me over almost a dozen very big puissance walls, and I know that if my life depended on jumping one of them tomorrow, I would only hope to see it looming larger between those wise gray ears of his.

I asked Jim Wofford, Mike Plumb and Stephen Bradley which horse they would ride if their lives depended on getting around the biggest, longest, toughest cross-country course they’d ever seen; and I asked George Morris and Anne Kursinksi with whom they would trust their lives over the most difficult grand prix course in the world. Here are their answers:

|

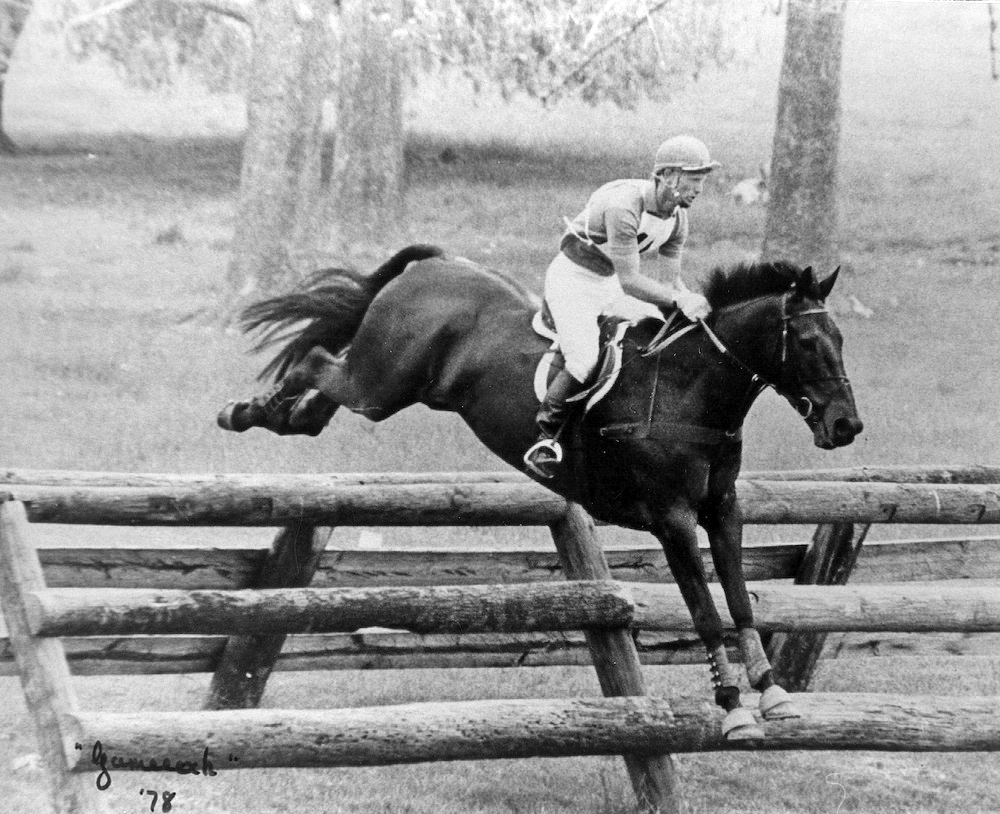

Jim Wofford/Carawich Jim Wofford would choose to be mounted on Carawich. Carawich was a 16.3-hand brown, “probably 7/8 Thoroughbred” Irish-bred gelding. His sire was the Thoroughbred Scratchy, “who bred four-mile point-to-pointers and horses to race over banks.”

Jim purchased Carawich in 1977 from British rider Aly Pattison, who had won the Burghley CCI (England) on him in 1975 and completed the Badminton CCI (England) on him in ’77. Jim said that one of Carawich’s most remarkable features was that “he always rode, to me, as if he had walked the course. He had an intuitive understanding of what he was seeing in front of him, even as he came to a complex at a fast gallop.” Jim feels that Carawich had the “typical upper level even horse’s disdain for fences which knock down. If I rode him well, he would go clear or have one rail down.” On the flat, Carawich could be difficult. “He was always sharp, always edgy, tough to keep steady,” said Jim. Before the 1978 World Championships at Lexington, Ky., Carawich had no time or jumping faults at any of the selection trials. “He wasn’t super fast, but he could hold his speed,” said Jim. He finished 10th in the World Championships after a fall at the decisive Serpent fence late in the course. In 1979 he was fifth at Badminton, and in 1980 Jim and Carawich won the individual silver medal at the Alternate Olympics at Fountainebleu, France. “The bigger the crowd, the bigger the event, the more Carawich rose to the occasion and pulled harder and tried harder,” said Jim. |

|

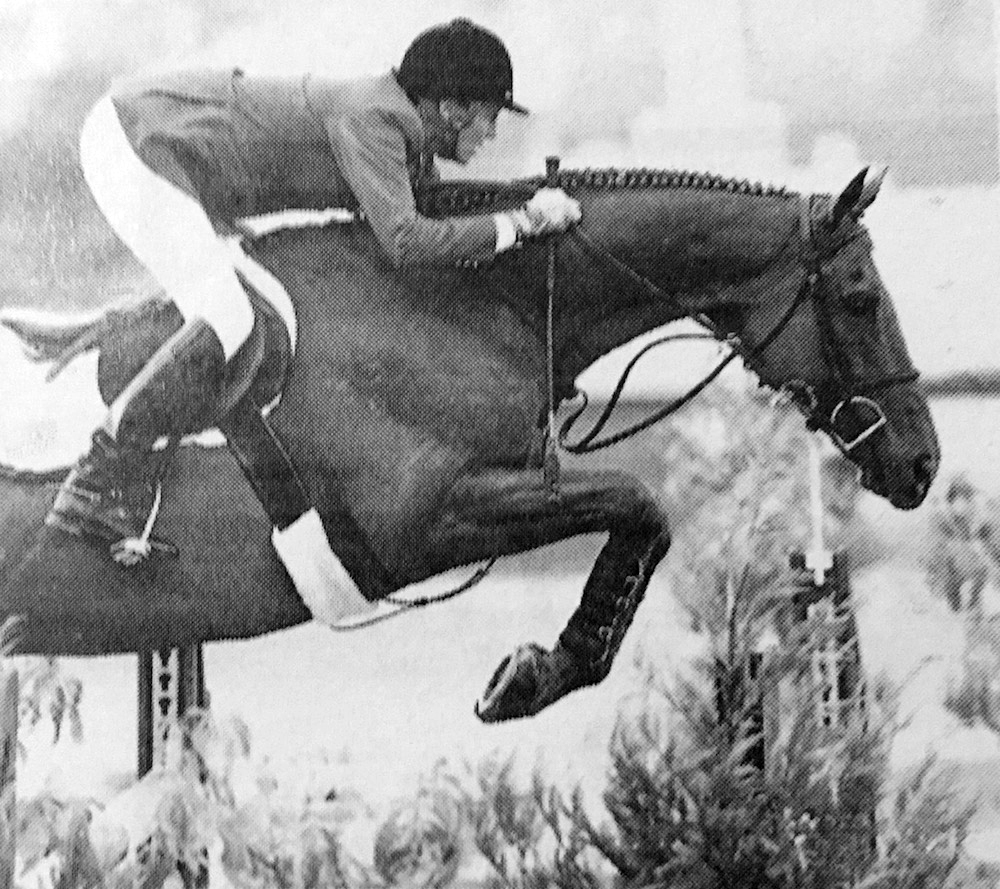

Stephen Bradley/Sassy Reason Stephen Bradley says of the 16.1-hand, dark brown, Thoroughbred gelding Sassy Reason, “I literally trusted him with my life. I would ride him down to anything. He was always 120 percent safe.” Sassy Reason “was a typically refined American Thoroughbred, a bit light-boned, but he has the balance and spring of a cat.” ADVERTISEMENT

Sassy Reason was by Limit To Reason, a son of the champion American race horse sire Hail To Reason and out of Sassy Mite. Stephen says of Sassy Reason: “He was the best-balanced horse I ever sat on. He was one of those horses who, when I got us to a fence as wrong as it’s possible to get, found a ‘fifth leg,’ and I never felt him do it.” Sassy “could be tough on the flat because the atmosphere of a big event could create tension and anxiety. Show jumping was probably his best part because he was so well-balanced and steady in his rhythm, and easy to see a distance on, plus which he didn’t like to hit a fence.” Because Sassy was such a careful jumper, “on fences where the ground dropped away so he couldn’t see the landing, I had to ride him more aggressively.” Stephen and Sassy Reason won the Checkmate CCI*** (Canada) three years in a row, completed the Barcelona Olympics, and in 1993 became only the second American ever to win Burghley. |

|

Anne Kursinski/Eros Anne Kursinski says of Eros, her 10-year-old, Thoroughbred gelding, “He’ll turn himself inside out to jump clean. He knows where the jumps are and where his body is. He’s extremely courageous, and he thinks he can jump anything. He’s a little cocky and feisty, which I love.”

Although Eros, a chestnut, 16-hand gelding, was foaled in Australia, his pedigree is 75 percent American. He is by Family Ties (Sir Ivor—Fanfreluche, Northern Dancer) and his dam, Tudor Success, is by Wavering, a son of the California-bred Swaps. Anne said, “The hardest thing with him, because he’s so sensitive and sights in on his fences, is to stay out of his way and allow him to do his thing—and really trust him. His only fault is that crowds get to him. He’s a blood horse, a real Thoroughbred.” Anne tied for first overall in the 1996 Olympic selection trials with Eros, and in August they were part of the USET’s silver-medal team in Atlanta. “The less I do—literally no leg, nothing—the better he goes. The biggest courses, the bigger the crowds, the more they would cheer, the better he’d jump,” she said. Anne gives him the biggest compliment: “I’m so confident that I could walk into any ring, and I’d never think the jumps are too big.” |

|

George Morris/Sinjon For George Morris, who’s ridden internationally for nearly 40 years, the ultimate horse was Sinjon, on whom George missed winning the individual Olympic bronze by 1 fault in Rome in 1960. “Sinjon was 15.3 ½, a weedy, wasp-waisted Thoroughbred. He was by Vino Paso, and Argentine-bred grandson of The Tetrarch, out of Helen Abigail, a granddaughter of Man o’War.

George remembers he was at a horse show when he first saw Sinjon. “I was watching Harry deLeyer jumping the top of the standards in a second year green hunter class on this weedy little bay horse,” said George. “I tried to buy him right there, but Harry said, ‘No, I won’t sell him to you, but I’ll give him to you after I show him this fall at Madison Square Garden.’ I knew this couldn’t happen, but Harry that knew it could.” ADVERTISEMENTThat November, George sat in the upper seats at the National Horse Show (N.Y.), watching Harry show Sinjon in a jumper class. A little later, “I saw Harry come running up the stairs to where I was sitting. ‘Where do you want me to send this horse?’ he asked me. And that’s how I got him,” George said. “I played with him that winter when he was a 5-year-old and then took him to Tryon, N.C., to train with Bert de Nemethy. He never went green. He was hot and bouncy—incredibly bold but incredibly clean.” George took Sinjon to Europe with the U.S. Equestrian Team in 1958. “You could run him as fast as you could go and he’d win, or show in a Nations Cup or a grand prix and he’d win those too. He had the greatest heart. He never stopped at a jump,” said George. Before the Rome Olympics, George and de Nemethy discussed whether George should ride Sinjon or the more powerful Night Owl, who wasn’t always as careful as Sinjon. “Rome was delicate jumping, with thin, brown rails, so we decided to use Sinjon,” George recalled. Even though George has ridden many horses in the years since Sinjon, “I’ve never had a horse before or since with his combination of heart, stride, scope, carefulness and agility.” |

|

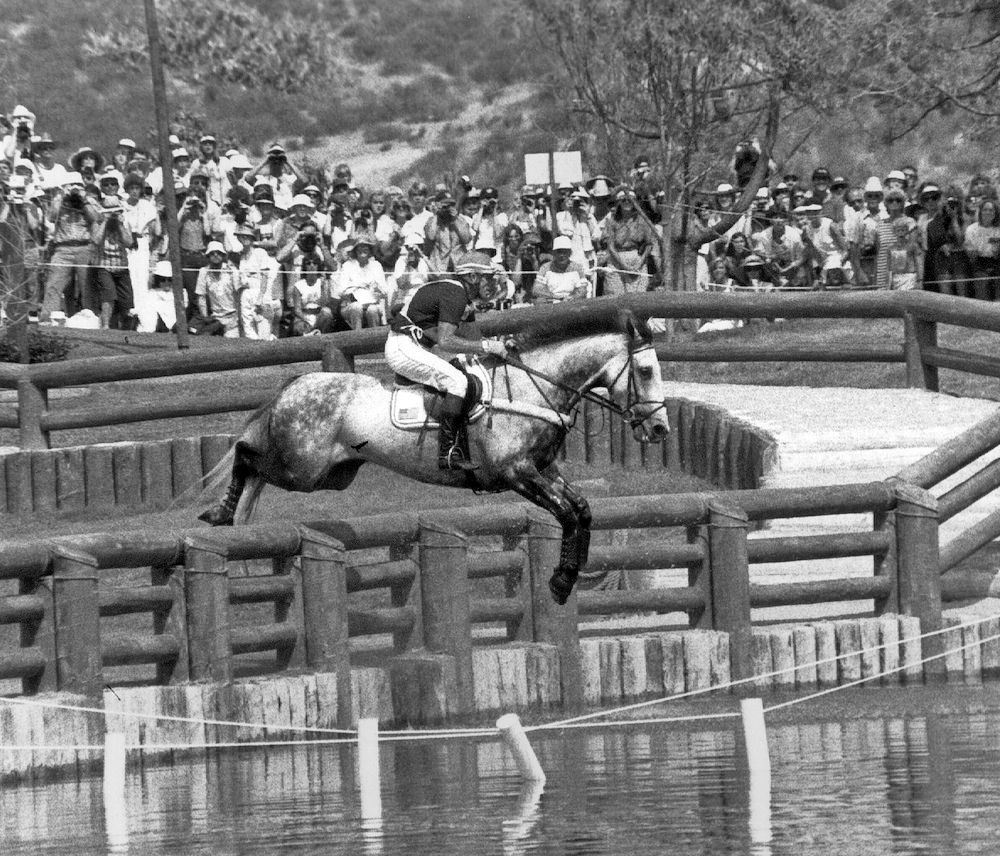

Mike Plumb/Blue Stone Mike Plumb has completed dozens of horses in nearly four decades of international three-day eventing, but it’s of Blue Stone that Mike says, “Whatever I aimed him at, he jumped. Give him half a chance—no, one quarter of a chance—and he was going to jump.”

Blue Stone was a gray, 16.3-hand, Irish-bred “probably 7/8 Thoroughbred, if that,” purchased by the Miles River Syndicate to loan to the USET Three-Day Team. Mike got the ride on him before the 1982 World Championships in Lümuhlen, Germany. They were part of the team that won the bronze medal that year, and in 1984 Blue Stone produced the important third score for the gold-medal team at the Los Angeles Olympics. In 1986, Mike rode him “with a bunch of broken ribs” at the World Championships in Gawler, Australia. “The intriguing part,” Mike said, “is that I couldn’t ride him on the flat to save my life, but he was so genuine and so honest that even though he wasn’t broke by my standards, I always felt comfortable taking the fast, difficult options. At the bank complex at Los Angeles, I was the first American rider to go, and it was serious business. I went the short way, and it was just a breeze. At Gawler there was a corner combination where everyone went the long way. I went the short way. You could thread the needle with him.” Mike said that Blue Stone “was brave but he also had a lot of savvy. He wans’t a bully about being bold the way so many bold ones are almost half-crazy.” Blue Stone was always sound, and although he wasn’t fast, he would always finish. Even though Mike’s broken ribs made him unable to help Blue Stone at the difficult water complex at Gawler, Blue Stone made it through with an awkward jump. “He was a survival horse and he stood up. He’s one I would point anywhere and feel confident about it,” said Mike. |

The words from their riders’ mouths that describe these most elite horses aren’t always what we might to expect. In addition to complimentary phrases like “bold,” ‘honest,” balanced,” “tries his heart out,” “desperate not to hit a fence,” never stops,” “catlike,” cocky,” “feisty,” and “confident,” they say things like “wasp-waisted,” “sensitive,” “tough on the flat,” “nervous,” “aggressive,” “tense,” and “sharp.” One of the was a weaver. Two others were cribbers.

I think that very often the greatest horses, in the hands of lesser riders, simply vanish into oblivion and obscurity. Great horses are not often easy horses. They’re arrogant. They have big egos and idiosyncrasies and quirks and foibles. Most riders aren’t able to cope with their difficulties and the magnificence within remains undiscovered.

Horses of a lifetime do exist, but only for riders so skillful, tactful and courageous that they can unlock and reveal the brilliance of their equine partners.