Antique riding manuals can be both informative and entertaining.

Ever wondered what life was like for female riders 100 years ago? Three antique riding manuals, published between 1884 and 1912, shed light on the topic.

From deportment to training to fashion, these tomes show that the more things change, the more they stay the same. There’s some antiquated advice that strikes the funny bone in modern times, but there are also tried-and-true theories of horsemanship.

Each—American Horsewoman (1884), by Elizabeth Karr, Horsemanship For Women (1887), by Theodore Mead, and Riding And Driving For Women (1912), by Belle Beach—was directed specifically toward female riders.

Each—American Horsewoman (1884), by Elizabeth Karr, Horsemanship For Women (1887), by Theodore Mead, and Riding And Driving For Women (1912), by Belle Beach—was directed specifically toward female riders.

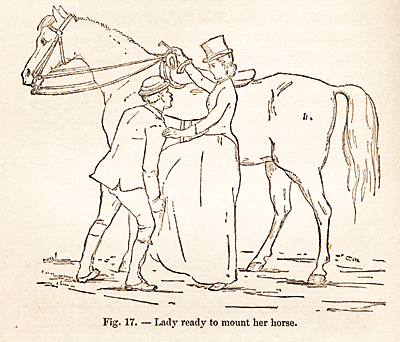

According to these books, at the turn of the century, an American horsewoman was expected to ride side-saddle with a groom in attendance, and to spend as much time choosing her riding habit as her horse. She was even to give careful consideration to her horse’s color, since, as Mead wrote, blood bay is the most suitable color for a horse, and sorrel definitely the worst.

Much of the old-fashioned tone of the books comes from their attitudes toward etiquette and social class. Judging from the authors’ assumptions, grooms were very nearly a given for the women reading these books.

Mead, arguing for women to learn horse training and care, wrote that a groom may watch his employer “with interest” if she works with her own horse. The rider should ignore these derogatory looks. She should, instead, examine her own horse with a practiced glance “in half a minute, while you are buttoning your gloves.”

Mead continued that the groom should ideally be “in a respectful attitude with eyes down.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Beach reminded her readers that brown webbing girths (instead of leather, or white webbing) “never look well and are liked chiefly by lazy grooms.”

All of the authors debated the issue of manners on horseback, and how genteel ladies could preserve their social graces while riding. Karr cautioned that: “Rudeness in the saddle is as much out of place as in the parlor or salon, and greatly more annoying to spectators. Because a lady loves her horse, and enjoys riding him, it is by no means necessary that she should become a Lady Gay Spanker, indulge in stable talk [or] make familiars of grooms or stable boys.”

All of the authors debated the issue of manners on horseback, and how genteel ladies could preserve their social graces while riding. Karr cautioned that: “Rudeness in the saddle is as much out of place as in the parlor or salon, and greatly more annoying to spectators. Because a lady loves her horse, and enjoys riding him, it is by no means necessary that she should become a Lady Gay Spanker, indulge in stable talk [or] make familiars of grooms or stable boys.”

In addition to the antiquated idea that servants assist all female riders, there are some old-school suggestions of rough training methods. Mead wrote that to signal a horse to trot, the rider should lay her whip (albeit “gently”) on the horse’s hindquarters while “incit[ing] to speed” with her heel. He also says you can stop a horse from rearing with “a smart stroke down the shoulder.”

Beach’s plan for a side-saddle rider to stop a rearing horse is to “make him fall on the off side by pulling his head to the side with all her strength,” which also goes into today’s don’t-try-this-at-home file.

What Not To Wear

Their readers’ appearance in the saddle was a primary concern for these authors. “A tall woman looks out of proportion on a small horse and a stout woman ridiculous,” wrote Beach.

Karr took the other tack, advising skinny equestriennes to use “a little padding around the hips and over the back

[to give] the desired effect of plumpness.”

According to Karr, “The naturally slender, symmetrical figure, when in the saddle, is the perfection of beauty, but she whom nature has endowed with more ample proportions will never attain this perfection by pinching her waist in. Let the full figure be left to nature, its owner sitting well in the saddle, on a horse adapted to her style, and she will make a very imposing appearance, and prove a formidable rival to her more slender companion.”

Don’t wear your hair in braids, Karr added, or they will stream out behind you, and then “an observer at a short distance will be puzzled to know what it is that seems to be in such an extraordinary state of agitation.”

For his part, Mead advised that: “No petticoats ought to be worn, but merino drawers.”

As well as fretting over her female readers’ presentation, Beach worried about them being considered manly because they liked the hearty outdoor sport of riding so much. Yet she also exhorted them to act as equals to men when the situation warranted.

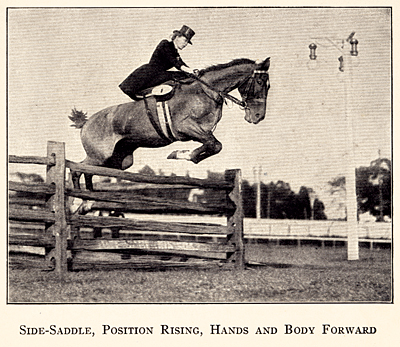

“When a woman hunts,” she wrote, “she enters a masculine field of sport, and in the hunting field she is meeting men on their own ground and on even terms.” Women, Beach believed, should not expect male hunters to fetch their dropped gloves or hats, and they should not expect to be allowed to go first over a fence.

| More Excerpts From The Manuals

“Sooner or later, and usually very soon, he will come straight towards you; then instantly relax his head, say ‘Bravo! Bravo!’ and stroke him on the face and neck. You will very likely hear him give a deep sigh of relief, like a frightened child. Give him a half a minute or more, according to circumstances, to look about and recover from his nervousness—for you will find that his nerves work a good deal like your own—and then begin again, allowing him after every trial a half-minute or so of rest.” ADVERTISEMENT“The position of a man in the saddle is natural and easy, while that of a woman is artificial, one-sided, and less readily acquired; that which he can accomplish with facility is for her impossible or extremely difficult, as her position lessens her command over the horse, and obliges her to depend almost entirely upon her skill and address for the means of controlling him.” “Lightness does not in any way denote weakness, for, behind the light touch, there must always be firmness, decision, and strength. Nor does lightness mean a touch so vague that it produces upon the horse’s mind an impression of vacillation. In riding it is most important for the rider, once she has made up her mind what to make the horse do, to make the horse do that thing and not allow him to do anything else. One might, indeed, say that lightness of hands is very closely akin to tact and that it is a means of inducing a horse to adopt as his own the will of his rider. |

Which is why, as she wrote, “No woman should go into the hunting field at all unless she is a thoroughly experienced rider and has complete confidence in herself.”

Karr, on the other hand, firmly discouraged female riders from hunting. “The author does not consider [the hunting field] a suitable place for a lady rider. She believes that no lady should risk life and limb in leaping high and dangerous obstacles, but that all such daring feats should be left to the other sex or to circus actresses.”

Practical Advice

These manuals looked forward to today’s harmonic riding theories. Beach’s huntswoman represented the equestrienne who eventually emerged from these books once all the period fashions and manners were sorted out: a self-assured, skilled rider who could handle any horse-related event, from a foxhunt to a country hack to a horse auction. She also trained and rode horses with firmness and compassion.

Mead, Karr, and Beach imagined that they were writing against a prevailing system of severe horse-breaking, and that they were putting forth a kinder method of training—more attuned to the horse’s needs and in sympathy with their mounts. Even though some of their methods (like the pulling down of a rearer) seem harsh, these writers saw themselves as teaching compassionate training.

Karr, for example, wrote that instead of “rough and brutal” schooling, “kindness, firmness, and patience” are the new way. And she placed total faith in her readers: “If she be an accomplished rider, she can do the greater part of her training herself.”

Mead added that riders should try to understand their horses, and realize that “what seems insubordination is in reality nervousness, which requires soothing, not punishment.”

And here’s Beach: “If a rider is fortunate enough to be gifted with lightness, she will be able to control her horse with a spirit of love instead of adopting the brutal method of controlling him by fear.”

Karr did worry that this “mastery” could result in a woman rider putting on airs, once she understood how much power she wields as an accomplished equestrian. So she reminded riders to remember her social position: “A lady should never seek to gain prestige by riding restless or vicious horses.”

Her strict standards extend to men, as well. If he couldn’t help a lady mount and dismount, Karr wrote, a man was not a “finished equestrian.” If the lady was “rather stout and not very active,” the man could always help her dismount by grabbing her around the waist.

Mead recommended some masculine assistance as well, even for his independent-minded readers. He wrote that young women about to take up horse training should “have a man—some friend or attendant—near at hand to give you confidence by his presence, and to come to your aid in case of necessity.”

Mead appealed to women’s senses by explaining how horses can give them power. “Yet only by tact and patience can you win that mastery over his every volition by which his splendid strength, courage, and endurance will seem to be added to your own,” he wrote.

Words Of Wisdom

Mead seemed confident that his readers would become just as strong and courageous as their horses, once they learned how to train and ride with assurance. He also made the crucial point that being competent with horses helps riders find available horses in the first place.

“A different, but equally practical, result of knowing something of horse training is that wherever you may be, you will have no difficulty in getting a mount—no small advantage either, as many an enthusiastic young girl can testify as she remembers the stony look which came over some comfortable farmer’s countenance when she confidingly asked to ride one of his round-bellied horses.”

Any rider knows that having horses at her disposal is the first step to becoming an independent and poised rider. If the 19th century horsewoman could pry the plowhorse away from that farmer by demonstrating her equestrian skill, she might have had a chance to practice some of Mead’s teachings.

Some of the topics Mead discussed do not trouble today’s riders—he used pages and pages discussing on which side a woman’s escort should ride—but other things have not changed at all.

“The acquisition of a saddle-horse by a young girl is usually a long and complicated operation, in the course of which her hopes are alternately raised and depressed day by day, to be at last very likely disappointed together,” he wrote. “The father hesitates, and few fathers there are who do not in their hearts long to grant the request; but he is a very busy man, and does not feel as if he could take any more cares upon his shoulders, and very likely he knows little about horses.”

Timeless Advice

Mead seems most modern when he insisted upon the horse as a reflection of his rider. With a fresh horse, he wrote,

“Try not to have an anxious expression of countenance, no matter what he may do, but to look serene and smiling,

as it will not only be more becoming, but will undoubtedly react upon your own feelings.”

In other words, the horse, as Sally Swift would write more than 100 years later in her classic Centered Riding, “How would you feel if your horse held his breath? Frightened, most likely. And that’s how he’d feel if you held yours.”

Beach had a similar idea of the connection between a horse and rider. “A horse,” she wrote, “has a mind which very readily receives impressions from the rider’s mind. For instance, a rider expects a horse to shy at some object; she will unconsciously impart that thought into the horse’s mind and the horse is almost certain to shy; but if she will say to herself, ‘there is nothing to shy at, we will simply go quietly by this;’ if she does not interfere with the reins and gives the horse absolutely no sign that she has any thought of shying in her mind, the horse will, nine times out of 10, if not 10 times, pass by the object without showing the slightest alarm. It is usually the rider that shies and

not the horse.”

As precocious as Beach was, she could not always see into the future, as evidenced by her comment that women leaving the side-saddle to ride astride was “a mere passing fad.”

Like Mead and Karr before her, Beach envisioned horse knowledge as empowering to women. Beach writes that women can find a horse “among the discarded polo ponies,” or at the auction marts, on the stock farms, at the race track, or through a “casual meeting on the road.”

In a time when a woman wasn’t even supposed to go riding without a chaperone, or saddle her own horse without a groom nearby, Beach had her out eyeing off-the-track race horses, which seems a step forward even from Mead and his young girl pleading for a horse from her father.

Beach was sly enough to differentiate between the “clever buyer who ‘has an eye’ and the buyer who ‘thinks she has an eye.’ ” With some serious saddle time, and with one of these books tucked under her arm, any turn-of-the-century rider with a little confidence could place herself firmly in the first category.