Hunter legend Kenny Wheeler died this week at 92. In his memory, we’re republishing this Living Legend article from the Nov. 5, 2012, issue of The Chronicle of the Horse.

Each morning, Kenny Wheeler makes his way the few hundred yards from his home to the main barn at Cismont Manor Farm.

He walks past the stalls that have housed famous hunters like Isgilde, Ruxton, Two For One and Weather Permitting, among many others. He straightens the forelock of a 4-year-old standing on the crossties, then runs a hand down his legs.

Wheeler chats quietly with the barn staff, shares a few jokes and then walks the short distance up the hill to the outdoor ring. There, he and Olin Armstrong—two men of few words but a perfect understanding—discuss the plan for the day for the first horse Armstrong is riding. Wheeler settles in to watch the horse go.

“Every day, that’s my life, watching those horses,” Wheeler said. Later, he brings out a yearling to work in-hand, teaching it manners and how to stand correctly.

Kenny Wheeler (left) might have won just about every honor that can be bestowed on a hunter rider and trainer, but it’s the daily training of horses in collaboration with riders like Olin Armstrong that makes him happiest. Brant Gamma Photo

Wheeler is unfailingly polite and has the manners of a classic Southern gentleman. He removes his hat, shakes your hand and gives a quick kiss on the cheek when greeting you. He might not speak first, but once you get him talking, there’s a deep well of stories. He’s got a wickedly dry sense of humor and the sly wink to go with it.

One thing Wheeler doesn’t do is boast. If he simply says, “He’s a nice colt—a beautiful mover and a beautiful jumper,” in his slow, Virginia drawl, you know the horse has the kind of talent to which most trainers would attach a string of superlatives. If Wheeler deems a horse a “good horse,” he means it.

The walls of his house are lined with accolades earned in decades of showing top hunters. He’s ridden champions at every major show. He’s won the Best Young Horse title at Devon (Pennsylvania) 37 times. For much of the past 50 years, he’s been one of the top hunter trainers in the country.

“He’s set the standard for hunters as far as quality, looks, movement, jumping style and technique,” said trainer Tommy Serio, who spent six years riding for Wheeler. “He’s given hunters what we look for today. He was ahead of his time as far as quality and class are concerned.”

But for Wheeler, it’s not all about the trophies and ribbons. He simply likes the process of training horses. There’s nowhere he’d rather be than standing in his ring with a young horse learning to jump in front of him.

“I love to watch colts and train young horses and bring them up. A lot of people like to buy them ready to show, but I like to make them,” he said. “That’s really why I’m doing it. I like to watch them learn here at home and then go to the show and see them progress.”

Wheeler’s fame may have come at horse shows, but the real story of his life centers around his horses, his family, his one true love and a farm.

Home

Driving along Rt. 22, which winds through the quaint village of Keswick, just east of Charlottesville, Virginia, is like taking a road trip back in time. Acre after acre of gorgeous green fields unfold, encircled by white board fence and framed by the backdrop of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Long driveways lined with stately trees lead back to sprawling farms. Unsullied by convenience stores or stoplights, the road looks much like it did 50 years ago.

Cismont Manor lies just a few miles north of Keswick on Rt. 22, tucked in amidst other historic farms. The tree-lined drive meanders between large fields filled with grazing horses. A fork in the road invites visitors to choose between the main house and the stables. Your best bet to find Wheeler is to veer left, toward the latter.

Kenny Wheeler knows a good horse when he sees one, and he’s shown young horses like Capitol Hill to Best Young Horse honors at the Devon Horse Show (Pa.) for decades. Molly Sorge Photo

The barn, tucked into a slight hillside behind the main house, isn’t showy. There are no chandeliers, just fluorescent lights. The front walls are painted cinderblock, not varnished pine paneling. Three walls of 20 stalls surround a small indoor arena, with a workmanlike wash stall, grooming stall and tack room. It’s not a showplace but a working barn.

In fact, the barn looks much the same as it did in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, when horses like Isgilde, Showdown, Ruxton, Stocking Stuffer and Just For Fun munched hay in the spacious stalls. “It’s identical to then. We re-did the tack room is all,” Wheeler said.

The main house is similar—elegant, but with its edges softened by years of good use by children and dogs. The walls of the Wheeler home showcase photos of horses, awards and family.

The Early Years

Wheeler has spent the last 45 years of his life here at Cismont Manor, and despite traveling the country for horse shows, his Keswick roots hold strong.

“I grew up three miles down the road from here,” he said. “My father managed a farm there. They had show ponies. That’s where I learned how to ride.”

When Wheeler was 15, he graduated from high school and struck out as a professional rider and trainer.

Wheeler’s early professional years were typical of the ’40s and ’50s, with a thriving hunter circuit in Virginia and plenty of show ring heroes to emulate. “I had some natural ability to ride, so I could ride fairly good to start, and then there were a lot of good trainers around at the time,” he said. “I watched them and tried to learn as much as I could. Cappy Smith was awful good, and I looked up to him an awful lot. He was good to me, and he was a great horseman. I really respected him.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In those days, shows were a one-ring affair, and everyone hung over the rail to watch the working hunters. Lavish tailgate lunches and evening parties made the shows as much a social affair as a competitive one. The four big shows of the Virginia circuit were Staunton, Hot Springs at The Homestead, Deep Run and Warrenton, and horses frequently shipped from show to show in boxcars on the train.

Wheeler started off riding for noted owner W. Hagyard Perry for a few years, then signed up to work for Mary Barben at the Keswick Stables. “She had a public stable, with boarders, and it was kind of the first one, because in those days it was all private. I showed for her for seven years and rode a lot of horses all day long, every day,” said Wheeler, who learned every aspect of the business from the ground up. When Barben retired, he moved on to manage the barn for famed hunter owner and rider Peggy Augustus.

“She had great horses like Waiting Home and Little Sailor, who was the best,” Wheeler recalled. “I worked for her for seven years. I rode some, but she mostly showed.”

In the early ’60s, Wheeler took a job at Cismont Manor Farm, training for his future wife, Sallie, and found home.

True Partners

Sallie, a daughter of the famed Busch family, had bought Cismont Manor, building the barns and bringing horses there. She was an avid and successful hunter rider.

“We met at shows, and I’d known her for a number of years before I married her. She was a beautiful woman and a special person,” said Kenny.

They married in 1965, a couple who were lucky to share an unwavering devotion for each other and their horses. “She loved horses, and I loved horses. That’s what we did,” Kenny said.

Sallie’s vivacious, sunny personality and Kenny’s reserved, humble character meshed perfectly. “They created a great balance for each other,” said their son, Douglas. “My dad has never met a stranger; he can talk to anyone, but he’s quieter. My mother had a very outgoing, energetic personality.”

In the 1960s, Kenny Wheeler and his wife Sallie’s Isgilde were just about unbeatable in the regular working hunter division. Chronicle Archives Photo

In the early days of their marriage, they also shared the ride on the great hunter Isgilde. Sallie had bought the warmblood mare, who’d been trained in dressage and shown in the open jumpers by Frank Chapot, and Kenny found the key to her success.

“When we got her, she’d been shown a lot, and I think she was a little on the sour side,” he said. “We started riding her through the country, and I think that made her happy. Then her jumping was just there. She could jump 5′ like nothing, and she was a beautiful mover with beautiful style. She was just made for hunters. She was lovely. Sallie called her Precious. She would walk up to her and put her hand out, and she’d shake hands with her. She was Sallie’s favorite.”

Isgilde showed to unprecedented success with Kenny in the regular working division, including five Devon championships, and with Sallie in the amateur-owner classes until the ripe age of 17, when they retired her. They tried to breed her a few times, but unsuccessfully, so Isgilde lived to the age of 35 in a field at Cismont Manor. She’s buried in the front yard of the main house.

“If you train horses, you always like to have a great one, and she was just a great horse,” Kenny said. “She was the only horse we’d never sell. I can hardly remember going to a show where she didn’t win a class or was champion or reserve. She was a sure thing.”

Into the ’60s and ’70s, Kenny and Sallie became a formidable team in the hunter divisions, buying, developing and selling many famous names. Sallie had quite an eye for a horse, and then Kenny skillfully developed them into stars.

“Sallie was smarter about all kinds of horses,” Kenny said. “She had an eye you couldn’t believe for a horse, either a hunter or a Saddle Horse or a Hackney pony. If she said, ‘That’s a good one,’ you knew it was going to get the blue ribbon. She’s about the best I’ve seen at that.”

“They were in love not only with each other, but also with what they loved to do the most, which was every aspect of the horses,” Douglas said.

Kenny and Sallie’s passion for a beautiful conformation horse led them to the hunter breeding division, and Kenny started his domination of the Best Young Horse title at Devon. In addition, Sallie became active in showing American Saddle Horses (now called Saddlebreds) and Hackney ponies, winning just as many tricolors in that world as her husband did in the hunters.

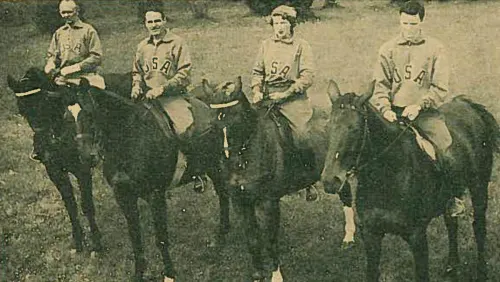

Sallie (left) and Kenny Wheeler (center) shared a remarkable love for one another, their horses, like Showdown, and their family, including son Kenny Jr. Gloria Axt Photo

As they grew their string, they also filled the house at Cismont Manor with children. Their first of three sons, Kenny Jr., was born in 1965, and Gordon, or “Cappy,” followed in 1970, with Douglas the last in 1972. “The farm was always a very active place,” Douglas recalled. “We always had different animals—plenty of horses, dogs, mules, donkeys and llamas. There was always some form of wildlife somewhere on the place.”

The boys all rode and spent their summers helping at the barn. “If we went to the barn, it wasn’t just to go ride and throw the reins at someone. We worked and learned the trade and had to do labor. We saw it from every angle,” Douglas said.

All three are involved in horses to this day—Douglas owns hunters, Kenny Jr. foxhunts and shows Saddlebreds, and Gordon also trains and shows Saddlebreds.

Ridden Enough

In the early ’70s, when he was in his mid-40s, Kenny decided to concentrate on training horses from the ground and hung up his show clothes. “I probably could ride as good as ever, but at the time, I was pretty busy training, so I just stopped,” he said. “I could ride pretty darn good, but I probably trained a horse better.”

There wasn’t a catastrophic fall or an injury that took Kenny out of the tack. He just decided it was time. “I guess I figured I’d just ridden enough. I never rode much anymore; I didn’t even get on a horse to exercise. I didn’t miss it. I just liked being around the horses,” Kenny explained.

ADVERTISEMENT

So he hired a succession of riders to fill the empty stirrups. Trainer Larry Glefke got his start riding for Kenny in the ’70s, and then Charlie Weaver spent the early ’80s showing Cismont Manor Horses. Weaver and Kenny collaborated on such stars as Ruxton, Super Flash, Two For One, Weather Permitting, Fun And Games and Stocking Stuffer, among many others.

“There wasn’t anybody to outride Charlie in the ring,” Kenny said.

“I was lucky through the years—I had good owners who trusted me and let me buy and show nice horses for them. That made a difference, because if there was a nice one, we could keep it a while. They’d eventually sell, but I’d get to show two or three years before they sold,” Kenny said.

When Weaver moved on in 1985, Serio took over the reins. “The time I spent with him was priceless to me. We were not only a trainer/rider combination, but we were good friends, and we’ve gotten even closer over the years,” Serio said. “We didn’t agree on everything—I was a little bit more modern. It was like pulling teeth to get him to try things like acupuncture on the horses. He’d say, ‘That’s hocus pocus.’ But he’d eventually give it a try, and he’d come around to it if he saw that it worked.

“He has a great eye for horses, but he also has the ability to extract the best out of any particular horse. He’s smart enough, too, to hire people to work with him to bring out all the things he saw in a horse when he hung up his tack. He has an uncanny ability not just with horses but with people, too,” Serio said.

The walls of the Wheeler family home are filled with memories of a lifetime spent with horses. Molly Sorge Photos

In recent years, Armstrong has taken over the riding duties at Cismont Manor.

Kenny’s legacy lies not just in the horses he trained, but also in the young professionals he shaped, such as Glefke, Weaver and Serio. “When you left there, you left with quite a foundation and confidence in your ability to go on and have your own business. He instilled that in you without question,” Serio said.

Giving Back

The Wheelers didn’t just concentrate on their own horses; they served on various boards and committees to further the sport.

“They weren’t just in the show ring and around the rail. So many times, you’d see them in the winter at different meetings, really trying to grow the sport. That was very important to them,” Douglas said.

Together, the Wheelers received the 1999 American Horse Shows Association Lifetime Achievement Award, and they earned many other individual accolades. Sallie’s crowning achievement was her incredible effort to bring the National Horse Show back to Madison Square Garden in 1996.

Kenny embraced Sallie’s love of the American Saddle Horses and Hackney ponies, too, even consenting to drive a Hackney at a show once. As a couple, they appreciated a good horse in any form. To this day, Kenny reads the Thoroughbred racing magazine The Bloodhorse and relishes a trip to the racetrack to put a few dollars on a horse. They befriended the Quarter Horse trainer Don Dodge.

“I met a lot of great people and great trainers over the years. I’ve enjoyed the people,” Kenny said. “I try to learn wherever I can. I don’t think you’re ever too good that you can’t watch somebody and learn something.”

Kenny’s world changed, however, on Sept. 21, 2001, when Sallie passed away. “We all very much rallied around him. She was without question the love of his life. They were head over heels for each other and always were,” Douglas said. “It absolutely was a blow. He had to reinvent himself a bit, because they had been partners for so long and been each others’ sounding board.”

“I don’t think you’re ever too good that you can’t watch somebody and learn something,” said Kenny Wheeler of his lifetime of training horses. Molly Sorge Photo

Fittingly, Kenny found his comfort in the barn, in the rhythm of cantering hoofbeats. “I guess the horses were what saved me. I missed Sallie, but I loved the horses. I kept doing that, so that kind of helped the down time,” he said.

Over the last 10 years, Kenny’s focus has shifted from the regular working horses to his first love, the young horses. He has just a few clients, primarily Cindy Keith, who is also a good friend. “I mostly just want to do it myself,” he said.

On any given weekend, you might see Kenny ringside at a local schooling show, evaluating a pre-green horse he’s training as it negotiates its first courses with Armstrong aboard. He might be comfortable at the nation’s biggest shows, but if a horse needs to start at a one-ring schooling show, that’s where he’ll enter it.

His philosophy hasn’t changed over the years. “The best word I can think of about him is simplicity,” Serio said. “He’s amazingly patient. Some horses we had were maybe slower learners, and he was willing to wait on them, and they turned out to be really good horses. His training was very much that it didn’t have to happen today. It might happen tomorrow, and if it didn’t, we’d wait a little longer.”

Kenny’s in no hurry. He just loves watching the horses.

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our November 5, 2012, issue.

Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked. Or you can purchase a single issue or subscribe on a mobile device through our app The Chronicle of the Horse LLC.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.