Eventing legend Jim Wofford died on Feb. 2 at the age of 78. In his memory, we’re republishing this article, which ran as a “Living Legend” feature in the April 2022 issue, the Kentucky Preview, of The Chronicle of the Horse.

James C. Wofford hacked along the winding gravel road with one hand on the reins and the other on the lead rope of the young horse ambling at his side. Four young men, each with another horse or two in tow, stretched out behind him. Few vehicles interrupted their trek along the quiet country lanes. On any other day, Wofford would have told jokes, scanned the fields for wildlife, and identified the birds as they flew overhead on the 4 1⁄2-mile journey, but today he was focused on their destination. He was going home.

Wofford and his wife, Gail Wofford, had been on the hunt for a place in Virginia since they’d moved there in 1971, but they couldn’t agree on a property.

“She would like the house, and I would hate the stables. I would love the stables and the facility, and she would hate the house,” says “Jim.” “We were stuck in that. We had just said, ‘Our only answer is that we’re going to have to build.’ ”

They sketched plans on the back of an envelope but didn’t have the money to do more until Jim’s mother, Dorothea “Dot” Wofford, died in 1973. After her four children divided up the proceeds from the sale of Rimrock, the Kansas farm where Jim was raised, he had just enough to buy 106 acres in Upperville, Virginia, and start building Fox Covert.

“On Dec. 7, 1974, Pearl Harbor Day, we saddled up at Brookmeade, a famous broodmare establishment of the 1940s and ’50s,” recalls Jim. “We rode one, led two down the hill from Brookmeade, north along Trappe Hill Road, which is the road that the cavalry traveled during the battles involving Middleburg and Upperville. We went past the site of a Civil War hospital, turned right on Millville, and we rode 2 miles up on the gravel road. We turned right on Greengarden Road and led them into the stalls.

“I shuttled the guys back, and they rode the remnants down, while I stayed and started sorting stuff out,” Jim continues. “By the evening of Dec. 7, I had 16 horses bedded down in my new facility. There were no dust bunnies; there were brass halters on the door; the brass was shined, and the place was ready for operation. I did not have a ring. I did not have an indoor yet. They were still under construction. That was the start.”

Jim Wofford was a mainstay of the U.S. eventing team in the 1960s and ’70s, before moving into governance of the sport. Karl Leck Photo

Jim had just turned 30. He’d already earned two Olympic team silver medals and an individual world championship bronze. His working student program, one of the first in the country, was quickly gaining traction. He’d married his childhood sweetheart and had two young daughters. Now, with the help of a family legacy that would feature heavily throughout his career, he had the beginning of the training base he’d dreamed of creating in the heart of Virginia hunt country. But would he have believed the riding accomplishments were just the start of an equestrian career that would encompass far more than international championships?

“A young married couple comes into the situation of the dog who caught the car,” jokes Jim. “Now what? I’ve been living by my wits ever since.”

Horses In His Blood

James C. Wofford entered the world on Nov. 3, 1944. The youngest of four, his next closest sibling was nine years older than him, and Jim readily admits his birth wasn’t in the family plan.

His involvement with horses, however, was no accident. Jim’s father, Col. John W. “Gyp” Wofford was a cavalry officer in the U.S. Army and competed on the U.S. show jumping team at the 1932 Olympic Games (Los Angeles). Gyp and Dot had purchased Rimrock Farm near Milford, Kansas, because it was adjacent to Fort Riley, which housed the U.S. Cavalry School. Rimrock was a working farm with cows and poultry, but horses were the main attraction.

Dot began her breeding program with an ex-Army Thoroughbred mare named Perk Up, and she went on to breed and/or own multiple Olympic horses including Hollandia, whom Bill Steinkraus rode in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Jim’s oldest brother, John E.B. “Jeb” Wofford, also rode in those Games, earning team bronze. Jim’s middle brother, Warren Wofford, was the alternate for the 1956 Olympic eventing and show jumping teams, and when he married Dawn Palethorpe Wofford, he gave her Hollandia, whom she competed in the 1960 Olympics for Great Britain.

After the U.S. Army disbanded the cavalry, Gyp helped found the civilian U.S. Equestrian Team in 1951 and became its first president. Not to be outdone, in 1959 Dot helped found the U.S. Combined Training Association, which is now the U.S. Eventing Association. Gyp coached the eventing and show jumping teams in 1952, and Rimrock became a training center for the team. After the Army auctioned off the cavalry horses in 1953, 73 remained unsold, and the Woffords took them in rather than see them euthanized. When it came to schoolmasters, Jim had some of the best, learning dressage aboard Jeb’s Olympic mount Benny Grimes, whom his mother bred, and competing in the junior jumpers with Rattler, the horse Col. John Russell rode to become the first American to win the Hamburg Derby (Germany) in 1952.

“I felt the pressure as a young man of being patted on the head, and people said, ‘Are you going to be as good a rider as your father and brothers?’ ” says Jim. “At about age 15 or 16 I started replying, ‘Better.’ Usually people would leave me alone after I said that.”

While Gyp’s influence may have loomed large in Jim’s life, his physical presence ended abruptly in 1955 when he died of cancer. Jim was 10. He describes himself as a “clone” of his father due to their shared red hair and says they were inseparable in his early childhood. Jim remembers following his father to the stables, riding out with him, and spending time together hunting for snakes in the creek. Gyp gave Jim his first rifle at age 8, sparking a lifelong passion for duck hunting and other sporting hobbies.

The period following Gyp’s death was a dark one for Jim. His siblings had moved out by then, and his mother drank to manage her grief. Jim didn’t ride for three years, instead wandering the Kansas countryside, hunting and fishing with a dog at his side.

Because of their rural setting, Jim didn’t have nearby children with whom to play. He attended school through eighth grade in a one-room schoolhouse that never housed more than 14 children total. At Pleasant View, Jim learned to speed read, a skill that would stand him in good stead as he turned to books first for companionship and entertainment and later for his classical equestrian education.

While his sister, Dodie Seymour, did her best to help raise Jim, she couldn’t always be there. “She had to go to Panama for two years because her husband was in the Army, and he was stationed there,” recalls Gail. “When she came back she swore [Jim] hadn’t washed his hands for two years.

“There’s a picture of him in jeans at her wedding,” Gail continues. “Little Jimmy wasn’t going to wear that outfit. Little Jimmy was stubborn from Day 1.”

Brains Over Talent

Stubborn was a quality Jim was going to need as he embarked on the next several acts of his life, whether he was fighting to stay in the tack at an Olympic Games, creating a new business model for the sport, or turning the governance organization on its head.

But first he had to get out of Kansas. At 13 Jim boarded a train for Culver Military Academy in Culver, Indiana. He credits the academy for teaching him discipline.

“There’s the right way, there’s the wrong way, and there’s the Army way,” he recites, only half in jest.

While Jim was not a great academic student, he pored over his true textbooks: “Training Hunters, Jumpers And Hacks” and “Riding And Schooling Horses” by Col. Harry D. Chamberlin; “Horse Training: Outdoor and High School” by Etienne Beudant; “The Forward Impulse” by Maj. Piero Santini; and “Riding Logic” by Wilhelm Müseler. Those books still hold a place of pride in his library, and he can point to each one on the shelf without looking.

“I can remember the exact place in the indoor arena [at Culver] where I felt the effect on my position of the relaxation of the ankles that Col. Chamberlin wrote about,” writes Jim in his memoir, “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years.”

His next stop was the University of Colorado, Boulder, which he chose because it was close to Gail’s boarding school. The pair had met in Colorado Springs, Colorado, when they were 13.

“As soon as I found out that he was into horses, I was [interested],” recalls Gail. “I did not have horses, and my parents disapproved. I pursued it despite them. We stayed connected through the horses. I would go visit him at his farm in Kansas for the summers. I went back to his dances at Culver. He came to my dances at my boarding school. We wrote lots of letters. He was a good letter writer, and his handwriting was discernable then.”

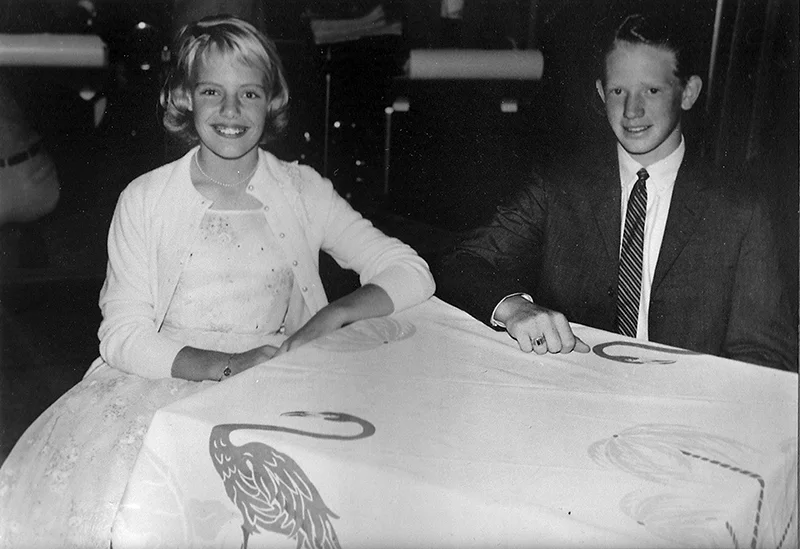

Jim and Gail Wofford, who met when they were 13, would go on to marry eight years later. Photograph From “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years,” By Jim Wofford And Reprinted With Permission From Trafalgar Square Books

Jim was named to the USET talent squad in Gladstone, New Jersey, in 1965, and he finished second in the national championships, but he was frustrated with his progress. His style of riding differed from eventing coach Stefan von Visy’s system, and Atos, his main ride, was an Appaloosa with limited scope who had originated on the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho.

“He didn’t come with a lot of good horses,” says Kevin Freeman, an Olympic teammate who was based at Gladstone with Jim. “[Mike] Plumb and [Michael] Page had gone through the equitation deal; Jim didn’t have much [formal instruction], and I didn’t have any. It was a matter of getting ourselves up to snuff. That was our job. He didn’t start out as a natural rider. Jimmy did a lot by brains rather than by being a wonderful athlete.”

It didn’t hurt that Jim approached everything with a sense of humor, too. “He knows every joke that’s ever been told, and he can recite them to you one after another,” says Freeman. “He’s my best friend. He’s so much fun to be around, and he’s very smart and very articulate. I admire him, and I wish I was half the person he is. He wasn’t a natural athlete, but he’s smarter than everyone else.”

In 1966 Jim married Gail and moved to New Jersey to continue training at Gladstone, but he had neither a top horse of his own, nor did he click well enough with a USET-owned horse to earn a spot on the team squad that year.

Jim Wofford earned his second Olympic silver medal aboard Kilkenny at the Munich Games in 1972. Photograph From “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years,” By Jim Wofford And Reprinted With Permission From Trafalgar Square Books

The Schoolmaster

“Then a schoolmaster arrived, purchased with questionable X-rays and the caveat that he might last a year or 18 months, but he’ll be a good schoolmaster,” says Jim with a Cheshire Cat grin. “The ‘schoolmaster’ took me to several national championships, winning one of them, two Olympic Games silver medals, and one world championship individual bronze model. That was some schoolmaster.”

That horse was Kilkenny, or “Henry.” An Irish Sport Horse by Water Serpent, he had competed in the 1964 Olympic Games (Japan) and won team gold at the 1966 World Championships (England) with Irish rider Tommy Brennan.

ADVERTISEMENT

“They only got Kilkenny because he was cheap, and the people in Ireland thought he was done,” says Gail. “We had to give him a holiday before he came. He was a young man’s horse. Not everyone could have ridden him.”

At 23, Jim was up to the job, and he shared Henry’s dauntless enthusiasm for cross-country, riding him to his first national championship in 1967 and earning team gold at the Pan American Games (Manitoba) as well, despite having two rotational falls early on course.

Henry not only helped Jim earn his first team spot, but he also played a crucial role in keeping him out of Vietnam. In 1967, Jim had two choices: volunteer or be drafted. On the advice of Col. Ralph Mendenhall, Jim volunteered and was assigned to temporary detached duty after finishing basic training. That meant his job was to train for the Olympic Games rather than board a plane bound for Southeast Asia.

Although Jim holds the military in high esteem and views it as essential to his path as a horseman, he doesn’t regret missing out on Vietnam.

“I’ve been around too many veterans, none of whom discuss their experiences with me because I have no context,” he says. “The written word, the spoken word, the video does not convey that experience. I don’t want to have that PTSD, that scarring. I want to understand it. I want to continue to believe there are some things worth dying for. They are few, but they exist.”

Jim and Kilkenny continued to be a shoo-in for every team through 1972. The pair won team silver at the 1968 Olympic Games (Mexico) despite a fall in show jumping after Henry slipped due to a broken caulk in his shoe. Jim had the shoe plated in silver, and it still hangs in his bar. He then won individual bronze at the 1970 World Championships (Ireland) despite a fall on cross-country, as the course was so tough that almost every competitor fell.

The 1972 Olympic Games (Germany) marked another Olympic team silver, although Jim felt he’d let down the team when they finished with two refusals and a fall. When two Israeli athletes were killed by Palestinian terrorists at those Games, it highlighted for Jim the intense and almost absurd tunnel vision maintained by Olympic athletes.

Aboard Kilkenny, Jim Wofford won two Olympic team silver medals (Mexico in 1968 and Germany in 1972) and an individual bronze medal at the 1970 World Championships (Ireland). Karl Leck Photo

“My sport was over, and we were outside the village,” he recalls. “It was a terrible tragedy that was an inconvenience for us because we needed to get back in to start packing to go home. [My attitude was,] ‘It sucks to be an Israeli. Can I stay until Monday because I’d like to watch the team jumping?’ ”

He did stay, and at the last minute ABC officials asked him to step in as the expert commentator for show jumping. “Sixty-five million people heard my voice at the Olympic Games with Chris Schenkel,” says Jim.

He also received some advice from the legendary sportscaster that he never forgot. “He’s the one who told me, ‘Say anything you like; just remember the kid’s mother is listening,’ ” says Jim. “Meaning you could be critical, but you had to be fair, and you had to understand.”

Henry retired in 1973 and went on to foxhunt with Gail for four more years. While Jim would tell you every horse he rode deserves a place in his story, the next big one didn’t come along until 1977, when Carawich entered his life.

“The Most Marvelous Equine Intellect”

Jim describes his first meeting with “Pop” as mythical. He was coaching at the Badminton Horse Trials (England), standing next to famous trainer Lars Sederholm as they watched the first horse inspection.

“I suddenly noticed a big, handsome, mealy-nosed, dark brown horse walking toward me,” Jim writes in “Still Horse Crazy.” “Just as he got next to me, he stopped and turned his head toward me. I had the sudden eerie feeling that he was looking directly into my eyes—that I had been singled out and was being sized up.”

Sederholm informed him that was Carawich, and he wasn’t for sale. Half a year later his owner became pregnant, and Jim borrowed against his life insurance policy to buy the Irish Sport Horse (Scratchy—Polly’s Vaughan).

“Lars and I have laughed about that a couple of times since then,” says Jim. “What would have happened in my life if I had my back turned when he went by, and he hadn’t seen me and stopped? My career probably was over, and I would have gone on to coaching.”

Aboard Carawich, Jim Wofford contributed to the 1978 World Championship team bronze medal in his first run at Kentucky, earned fifth as the highest-placed owner-rider at Badminton (England) the following year, and secured individual silver at the alternate Games in 1980 (France). Rosanne Berkenstock Photo

With Pop, Jim was back in the spotlight, contributing to the 1978 World Championship team bronze medal in his first run at Kentucky, earning fifth as the highest-placed owner rider at Badminton the following year, and taking individual silver at the alternate Games in 1980 (France), the riding accomplishment he remembers with the most pride.

“I had strict instructions, to go clean and take my time, yet when I struck off on Phase D, I had to decide to ignore the instructions,” says Jim. “I had the horsemanship to let my horse run his race, making the decision immediately that’s not going to work; I have to do this. ‘I have to do this’ boiled down to me hanging on like grim death and restraining him from reaching his absolute speed without fighting with him. The most marvelous equine intellect of the 20th century just took charge.”

This plan worked out fine until they came around a corner and saw a woman pushing a baby carriage in their path. Jim yelled but made no effort to avoid her. “The mother pushed it and leapt into the brush as we went by,” he recalls with a laugh. “I never looked back. I hadn’t made contact, and she wasn’t supposed to be there in the first place!”

That same year Jim rode USET-owned Alex to the national championship, and he and Pop followed that up with a wire-to-wire win at the Rolex Kentucky Three- Day Event the next spring. However, a broken pedal bone at Luhmühlen (Germany) in the summer of 1981 meant Kentucky would be Pop’s last major championship.

Jim Wofford first met Carawich at the Badminton Horse Trials (England), and in 1979 they finished fifth there, as the highest-placed owner-rider pair. Photograph From “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years,” By Jim Wofford And Reprinted With Permission From Trafalgar Square Books

A portrait of Pop hangs in Jim’s library across from his medals, which are individually framed. Does he still think about Carawich, more than 40 years later?

“All the time,” he whispers, his throat clenching on the words.

“And don’t forget him,” Jim continues with tears in his eyes as he points to a painting of another dark bay. “That’s Kilkenny. Look at him, he’s slightly worried he’s not trying hard enough.

“They were the correct horse at the correct time,” he continues after regaining his voice. “Later in my career, I would not have had the nerve then to ride Kilkenny. The courses were starting to be flexible. Kilkenny was not flexible. On the other hand, Carawich would have been so much smarter than I was at age 21 that I’m not sure I would have suited him. I would like to think so, but I don’t know.”

The Alphabets

Jim officially hung up his show clothes in 1984 after attending the Los Angeles Olympics as the non-riding reserve. While he still taught clinics on the weekend, he leased his barn to student Karen Lende O’Connor and went to work selling insurance for Collier Cobb.

“I saw plenty of soccer matches, track meets, and school plays, and enjoyed watching [my daughters] Hillary and Jennifer grow up,” he writes in “Still Horse Crazy.” “My hours were regular, and the paycheck was nice.”

Jim Wofford with daughter Hillary at Essex (New Jersey). “I don’t think it was a good work-life balance looking back,” Jim admits of his heavy travel schedule as a rider and trainer. “I just think I had such a strong countervailing force, that Gail’s maternal force was so powerful that it worked.” Photo Courtesy Of Jim Wofford

The horse world had other plans for Jim though. In 1985, Diana and Bert Firestone asked him if he would ride O’Connor’s horse The Optimist at Kentucky the next spring while she competed at the world championships in Australia. Jim agreed and ended up winning. That brief victorious return to competition coupled with a growing clinic schedule and the knowledge that he was next in line to be president of the American Horse Shows Association led Jim to reconsider once again, and he gave notice in 1987.

Jim’s introduction to equestrian sport governance had begun long before that. In 1971, Jack Fritz convinced him to become secretary of the USCTA. That summer, Jim attended his first AHSA board meeting and was plunged directly into the fight to stop equine doping, which was being led by attorney Ned Bonnie, who re-wrote the drug rules in 1970, and eventual AHSA President Dick McDevitt, whose barn was burned in the height of the battle over reserpine use.

Jim supported their efforts and became lifelong friends with Bonnie, who helped him implement the change he counts as his biggest contribution to sport governance.

“People underestimate the importance of the move, when I found a parade and stepped in front of it, to change the American Horse Shows Association, an association of horse shows run by managers and a few rich owners, to an individual membership organization. We still follow that model today, with all the implications that flow forth from that,” says Jim.

“In the early ’70s I had some rule change that I wanted to support or oppose—I can’t remember which—and I found out to my horror that I couldn’t vote,” he continues. “I was an upper-level rider with a bee in my bonnet. I didn’t have a vote, and I didn’t have a voice.”

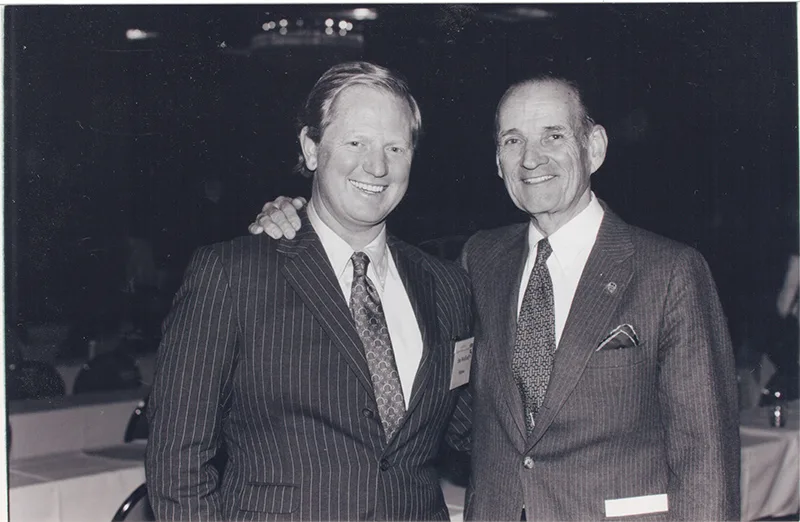

After his riding career, Jim Wofford played a major role in governance of the sport. While serving as American Horse Shows Association president, Wofford worked with USET President Bill Steinkraus to defend the international team selection procedures. Brant Gamma Photo

Board members underestimated Jim when he first joined. “Because of my mother and father, I had a leg up on other people,” he says. “Everybody said, ‘Oh, that’s Dot and Gyp’s cute little redhead boy. I remember him at Stockholm or Helsinki or whatever.’ Little knowing they were having the camel putting his nose into the tent.”

By 1981, he had become vice president, and he and Bonnie had convinced the board to change the AHSA’s structure to a membership organization. “Through education and general American common sense, [they came to recognize] this is wrong,” says Jim. “These people are telling me how to show my horse, and I can’t disagree. [My only options are] I can go to the show manager, or I can write a letter to the editor of the Chronicle.”

Before serving as president, Jim read The Federalist Papers and the lesser-known Anti-Federalist Papers in preparation. “I’m just curious about stuff. Always have been,” says Jim. “The Federalist Papers are all about compromising. What were the bedrock principles of Madison? Why did he disagree so strongly at times with Hamilton, who is now more famous thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda? If you study history, and you are curious, and you study history not as a series of connected and related dates but as the accumulation of wisdom, then you’re ahead of the game.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Jim served as AHSA president from 1988 to 1991, and during his tenure on the AHSA Executive Committee he helped implement term limits for officers and board members, instituted a system of breed and discipline directors to improve communication with the affiliates, and worked with USET President Bill Steinkraus to defend the international team selection procedures.

While he was no longer in governance during the battle between the AHSA and USET for which organization would become the sport’s governing body in the early 2000s, he did weigh in on the controversy.

“He was real smart about that whole deal and was very useful behind the scenes when it transferred from USET to the AHSA,” says Freeman. “It was always a strange thing. The AHSA was the governing body, but the USET selected all the riders. The USET wanted to be the governing body. There was a lot of back and forth there. Alan Balch did a good job with that whole thing. Alan Balch was out front, and Jimmy was behind the scenes. It wasn’t an easy thing. There were a lot of egos to get straightened out.”

While Jim jokingly refers to his involvement in governance as “the alphabets” in reference to the endless acronyms, he gave back tirelessly to the sport. At one point he was an officer in the USCTA, USET and AHSA as well as sitting on the Fédération Equestre Internationale Eventing Committee and working with the U.S. Olympic Committee as the first equestrian athlete representative on the board. U.S. Equestrian Federation officials presented him with the organization’s highest honor, the Lifetime Achievement Award, in 2012.

“I felt a sense of responsibility to the sport,” says Jim. “I had lifelong family advantages, my father’s involvement, me being viewed as natural successor, a family seat on the board, and a sense of obligation, which I no longer feel. I had all these advantages and a natural curiosity to go in there and look at the machinery and tinker with the motor.”

Jim Wofford can usually be found with a black Labrador at his side at East Coast events and clinics. Annie Jones Photo

He stepped down from his U.S. governance commitments in 2001 when he became the Canadian eventing team coach. “When I left the Canadians under amicable circumstances in the fall of 2004, I resigned from my [Canadian governance] positions,” says Jim. “I don’t think I ever took a committee assignment again.”

Instead, he pressed the next generation into service. “You had to step up; you had to step up early,” says Olympic gold medalist and former USEF President David O’Connor, who counts Jim as one of his biggest influences. “You had to step up in your 20s. It’s a weakness in modern day sport. You step up and listen and give back. It was required of all of us who were part of the game. It’s a small niche sport. If you don’t take care of it, it goes away. You have to be a caretaker for the next generations.”

David says Jim taught him to see the big picture rather than focusing on the microcosm. “We don’t have enough people who think with scope,” he says. “It’s what advantages them personally instead of the scope of the sport and the discipline, the scope of how you fit into the picture, how sport fits into society. Jim knows where he fits, where equestrian fits. We don’t have enough people doing that now.”

The Next Generation

David is one of a parade of top equestrians who count Jim as a current or former mentor. Beginning with Don Sachey in 1971, Jim pioneered the working student model as a means to earn an income while retaining amateur status. Sachey, who won team gold at the 1974 World Championships (England), paid board instead of paying Jim for his riding lessons, and that meant Jim still technically qualified as an amateur.

“I grabbed the third rail of where the sport was going,” Jim says. “There was no prescience; there was no predesign involved. That was where I was at the moment, and I caught lightning in a bottle.”

Jim took his working student program to Fox Covert, his home in Upperville for the last 48 years, and the farm quickly earned the reputation as the training grounds of future team riders. Among those young men ponying horses over to the new farm was Wash Bishop, who would become Jim’s teammate at the 1980 Alternate Games, and Tad Zimmerman, who was the reserve for the 1976 Olympics (Canada).

“Jimmy was the go-to guy,” says Zimmerman, who is still a lifelong friend and a master of the Piedmont Fox Hounds (Virginia). “He got me to the short list, got me to the team. He was very disciplined and thoughtful. He made us read; he’s got a pretty intellectual approach to it all. He was an early adopter of interval training. It was his program and plan that got the horses there. He’s the best teacher I’ve ever had in anything through life. He seems to know whether you need a pat on the back or a kick in the ass.”

“He was a pathway to the team,” agrees Bea di Grazia, whose husband, Olympic course designer Derek di Grazia, also rode with Jim. “Jimmy got me ready to go to Badminton fresh out of high school. I had just done a couple of open intermediates. There was a group of kids who were all about the same age who were fast tracked in a very safe and informative way. He gave us an outline every morning for the week. He was all about scheduling backwards from your ultimate goal. He gave us the whole mindset of a competitor. He was very clear about the training of the horse. Everything was about horsemanship. We did everything for the farm and for our own horses. Halters had to be polished, brass polished, not a speck on the floor.”

Jim kept meticulous records on every horse, beginning in 1965.

“Would you like to know what Carawich was doing in the spring of ’79? I can tell you,” he says. “And Thriller and Jones and March Brown, Karen’s horse. I can tell you day to day. Would you like to know what the training pattern was at Gladstone in 1965 when I showed up for the talent squad? It’s in my files down in the barn.”

While Jim learned military discipline under drill sergeants at Culver, he led by example rather than force. “We were meant to get to the barn, get everything squared away, muck the stalls, and then he would come,” recalls Zimmerman. “Wash and I were getting later and later, and he’d been away. He got up three hours early, went to the barn, did all the barn work, and was waiting for us when we tottered in 15 minutes late. He didn’t have to say a word.

“He expected commitment, and he got it,” Zimmerman continues. “He didn’t have to explain it. He set the example. He’s got a look, too. He can look at you and let you know that he’s unhappy with how things are going. He inspires the best effort. It was a lot of fun, too. We had fun and a lot of laughs.”

However, Jim and Gail maintained a separation between their family and the students. “Suzanne [Schardein] who worked for us [as Jim’s longtime groom] became part of the family,” says Gail. “I’d have the working students over for dinner every now and then, but it wasn’t constant. Jim’s as private a person as one will ever meet.”

Does he have a proudest coaching moment?

“I’m not bragging when I say I’ve had an awful lot of good moments,” says Jim. “I’ve had people who absorbed lessons here and went into the real world and were successful. One student went back to school, graduated with honors after slinking through his education previously, and when I quizzed him, he said, ‘I got ready for my exams the way you taught me to get ready for events.’ I have people that I know are limited in every aspect: horseflesh, money, time, physical nerve, and yet they bought into the program, and their successes are greater than some of my winners of Kentucky.

“How do you measure success?” he continues. “I have been successful as a coach. However you design it, I have people who were successful, just maybe not as riders. Many of my graduates must have gotten it by osmosis. They are aware of the responsibility they have to give back to their sport. They continue to do that to these days, many of them 30-year graduates, but they are still actively involved in sport administration in some aspect.”

A Teacher For Life

Jim had a rider on every team for many years, and five- star riders like Sharon White still turn to him for advice.

“I consider him my sensei,” she says. “He has a profound understanding and love of the horse. He’s very interested in everything that makes them tick. He’s so intuitive with horses and riders; this is someone who has spent a lifetime being interested in the horse.”

Jim Wofford, who’s always been an avid outdoorsman, fishes in Alaska with his daughter Jennifer. Photo Courtesy Of Jim Wofford

While Jim still teaches clinics, his greatest impact in this most recent act of his career may be as an author. “Training The Three-Day Event Horse And Rider,” which was published in 1995, was the must-read manual for preparing for a long-format three-day event. “Modern Gymnastics: Systematic Training For Jumping Horses” came out in 2013 and made Jim’s training system available to all. He’s published multiple other books including a raucous memoir of his non-horsey exploits, “Take A Good Look Around.” He’s also a longtime columnist for Practical Horseman, but his most famous article he calls “accidental.”

In 1998, then-editor of the Chronicle, John Strassburger, asked Jim if he would predict the results for the country’s first five-star event. Jim obliged and used his keen wit and insider’s knowledge to produce an unrestrained guide to the event that would make that issue one of the Chronicle’s most popular to this day.

“I’m glad it happened although it was accidental,” says Jim. “In many ways I’m sorry because it hurt people’s feelings needlessly. It was too candid. I didn’t realize the effect yet [of the Kentucky Preview]. It doesn’t matter what anybody says. It matters what you do. You are your record. The scoreboard does not lie. My success rate was pretty good. It’s better than you can get at the racetrack.

“I realize now that riders believed what they read,” he continues. “They didn’t understand it was being written for entertainment value as well as information, and that sometimes they had to take a little beating in the press.”

Jim retired from the column in 2020, which also was the first year since 1978 that the event didn’t run due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He still participates at Kentucky by leading a cross-country course walk for spectators and providing moral support to select riders.

“Every single thing, the foundation of what he is teaching and bases his theories on is so solid,” says Bea. “Nobody goes that far as to why a horse gallops the way it does, the mechanics of the horse, the system of the training, teaching a horse to jump. He can put so much color and flavor into it that everybody is getting so much out of it.

“He can still give information to the broadest base of people,” continues Bea. “He can really teach someone that knows very, very little and give them an awful lot at the same time as he can teach an elite rider. He sees the whole picture. He puts it together in a way that it carries everyone forward.”

Jim was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2020 and has since scaled back his teaching commitments, although he’s still scheduling clinics months in advance and fitting in fishing trips around his chemotherapy appointments.

“This has been the trip of a lifetime,” he says. “What comes next is the next great adventure.”

This article first appeared in the April 2022 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse. Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.