U.S. eventing legend Michael Page, who won the 1956 AHSA Medal Finals, won multiple Pan American Games medals and rode in three Olympic Games, is retiring this week from his job as head trainer of the Kent School (Connecticut) Equestrian Team after 28 years in the position. The school is holding a luncheon Saturday to celebrate his retirement and expects no less than 130 of his former riding students to attend. In honor of the occasion, we are sharing this “Living Legend” profile on Page that first ran in our July 10 & 17, 2017, issue.

Sitting on the floor of his family’s living room in Pelham, New York, a quiet suburb of New York City, Michael Page, then 15, dreamily flipped through an issue of Light Horse magazine.

Photographs captured horses and riders elegantly clearing jumps, alongside reports of international competitions. With each turn of the page, the teenager became more enthralled.

His father, Homer Page, sat in an adjacent chair, equally engrossed in his Sunday newspaper. Suddenly, he put it down and asked his eldest of five children what had so captured his attention. He wasn’t surprised to hear it was an equestrian magazine.

Homer had observed how his young son would become transfixed whenever a show depicting horses came on their television. Likewise, he’d witnessed Michael riding his bike 12 miles to the nearest barn where, at first, the budding equestrian climbed into the straight stalls, hopping from horse’s back to horse’s back down the length of the barn, and then later took lessons.

Homer recognized this wasn’t a passing fad for his son, this inexplicable draw to horses no one else in their family shared. And he knew quite a bit about inexplicable passions and the magic in pursuing them. He’d chased his own as a young man, deviating from the expected path to an Ivy League institution like his siblings and instead traveling to Europe to become a Shakespearean actor.

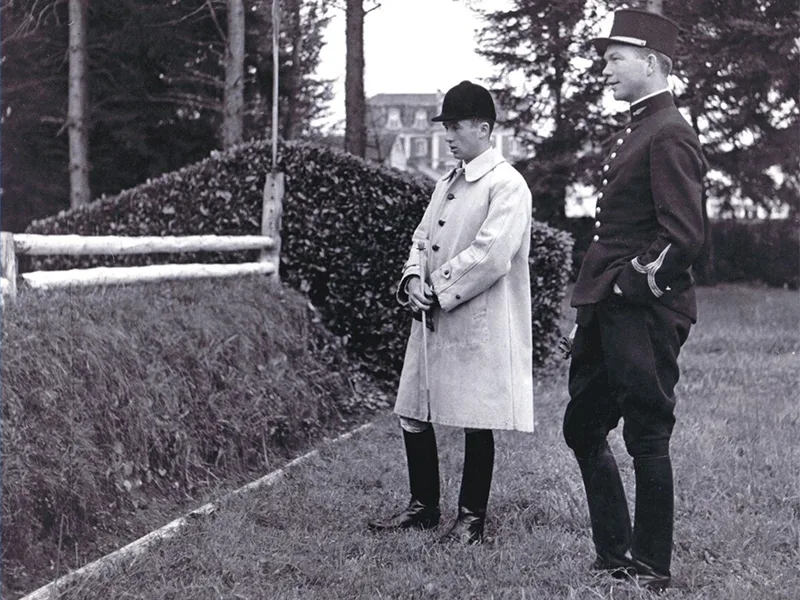

Homer Page encouraged and inspired his son Michael to pursue his passion. “His experiences as a young man really made a tremendous impact on my vision of what I was going to do and how I was going to do it,” says Michael. Photo Courtesy Of Michael Page

Homer would turn away from this dream when adult responsibilities intervened, and he returned to New York to run the family business making hat liners at Beatty-Page Inc., based near Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village.

So, on that afternoon in 1953, Homer did an extraordinary thing. He instructed his teenage son to write to a handful of barns advertising in back of the magazine to see if one could provide a formal equestrian education.

“He suggested that instead of going to camp over the summer, why didn’t I go to England and start getting an education in classical riding. He said, ‘You need more education. You need more experience. I, obviously, can’t do anything for you, so go where you can learn it. It costs the same as going to camp, but somebody has to guide you in your aspirations,’ ” Michael recalls.

“That was his thing, knowing that,” Michael says. “It was remarkable. I said, ‘Wow, that sounds great!’ He understood my need to expand my knowledge beyond what he could offer me.

“My father was special,” Michael continues. “And his experiences as a young man really made a tremendous impact on my vision of what I was going to do and how I was going to do it.”

That encouragement ignited a chain of occurrences that would eventually lead Michael to individual and team medals in three Pan American Games and to riding in three Olympic Games, bringing home medals from two and helping to secure U.S. eventers as a competitive force in the sport.

But, he was never fueled by a love of competition.

“I just wanted to ride,” he says. “I enjoyed figuring out the puzzle presented by the personalities of the horses I rode. But the competing part, no. My interest was in riding. I am a rider.”

Do Another 10 Circles

Before he found himself aboard a ship to England with his saddle and suitcase in hand, Michael was obsessed with riding.

“When I was 10, I used to watch black-and-white television, and my dream was to be a Pony Express rider. The world back then was different. The cowboys—they were heroes, and that always left an impression on me, right? Then part of what I saw, the visual image, was the horse,” he says.

Michael is telling me this in the cozy living room of his North Salem, New York, home, around the corner from the Old Salem showgrounds, down a dirt road lined with quaint stone fences. He’s lived here for 38 years with his wife Georgette (they have been together for 50 years) and raised their son, Matthew, in this charming house nestled within acres of preserved open space. Even though Matthew, now 38, lives in Washington, D.C., and works for NASDAQ, his presence is everywhere in their home with framed family photos on every surface.

“He is a great kid,” Michael says as I admire one of the snapshots. Matthew, while riding as a child and traveling back and forth to Florida with his parents, evolved into pursing other sports, like golf and baseball.

Michael, 78, has a habit of punctuating nearly every sentence with the word, “right?” making each statement sound more like a question as he recounts his life. It’s almost as if, even after all these years, he still can’t quite believe his luck in how his life has played out.

For as fortunate as he considers himself professionally he is quick to tell me, “The luckiest thing that ever happened to me is her,” and points to Georgette, whom he met at U.S. Equestrian Team headquarters in Gladstone, New Jersey, in 1966 when she was working as a groom for the team.

“The very best thing to ever happen to me was to walk into the team and seeing her sitting on that trunk. And she hasn’t changed. Without her—and my son …” he trails off with emotion in his voice before concluding, “My son is a piece of me and a piece of my wife and fortunately more of her.”

Georgette sits with us as we talk, sometimes chiding her husband that maybe he shouldn’t share that story and laughing at his jokes despite certainly hearing them repeatedly over the years. Their admiration for one another is palpable.

As for his other great love, horses, Michael says, “There was always something really clicking for me. Horses were something special in my life. It came from nowhere, and that was just who I was, right?

“And I don’t think I have ever been emotionally connected to the horse. It was more how the horse could create an opportunity to do something unique,” he adds.

There were the aforementioned bike rides to the now defunct Saddle Tree Farms as a young teen. While lessoning there, Michael caught the attention of a German immigrant named Herby Wiesenthal who kept his jumper Candlestick, a remount horse, at the facility. Herby had survived life as a Jew in Germany, the details of which were never discussed with Michael.

“Herby didn’t have any children, and he saw me as a boy who was passionate about riding and asked if I would like to ride his horse during the week,” says Michael.

“Candlestick had big feet and was sort of a clunker, but it was a horse to ride, so it was great! And Herby took an interest in me, saying, ‘Well, you love to ride, and I have a horse, and I could maybe help you a little bit along with your father,’ and so we started doing a little horse showing,” he says.

In 1956, Michael Page won the AHSA Medal Finals at Madison Square Garden aboard a former remount horse, Candlestick, owned by his friend Herby Wiesenthal. Associated Press Photo

It was after watching his son ride Candlestick and witnessing Michael’s commitment that his father suggested the summer in England.

Of the four places Michael wrote, he heard back from two, one being Eddie Goldman, who was an event and dressage trainer.

“It was the beginning of classical riding for me because I was so frustrated about putting a horse on a bit. Eddie would get on, ride, and the horse would go on the bit. I would get on, and the horse’s head would go straight up in the air, and then I’d get yelled at,” Michael says with a chuckle.

“All summer I rode in a little indoor ring, and when I came back, Herby and my father split the cost of the entries for equitation. We bought a single wooden trailer, and we went to the horse shows, and I qualified for the Medal Finals at Madison Square Garden on this remount horse,” he says.

His father would often watch him schooling, offering uneducated but supportive advice.

“My dad would say, ‘I still don’t think you make round circles. Do another 10 circles.’ And he knew nothing about riding, but he’d say, ‘Do another 10 circles,’ and so I would do another 10 circles, scratching my head,” Michael recalls with a laugh.

At the age of 15, Michael Page followed his father’s prompting to spend the summer training with Eddie Goldman in England, where he learned the tenets of classical riding. Photo Courtesy Of Michael Page

Educated Hands

Three years after he returned from his summer in England, Michael and his borrowed remount clunker Candlestick won the AHSA Medal Finals and placed third in the ASPCA Maclay. It was 1956.

“The judges were Ginny Moss from Southern Pines and Hope Scott, the [chair] of Devon. That is imprinted on my mind,” he says with a laugh.

Years later, he and Moss developed a friendship. He would often stop and visit her on his trip south for the winter and drop off memorabilia from the Olympic Games.

“One day I said, ‘Ginny, I’d like to ask you a question. How the heck did I ever win the Medal Finals at Madison Square Garden on a remount horse with a big brand down his neck?’ And she looked me straight in the eye, and without any hesitation said, ‘Michael, you were the only rider with educated hands.’ Just like that!” he says, still delighted after all these years.

This success reinforced what his father had recognized from the start, and he once again encouraged Michael to push on.

“My father sat me down and said, ‘You really have a passion for riding, and you have a very limited passion for school. Why don’t we think about the idea of instead of going to college, letting you go back to Europe and spend the next three or four years doing that?’ All my siblings went to college, but he recognized in me that there was a piece that was different,” he says.

Homer recognized it because he, too, had known it. While his siblings went to Princeton (New Jersey), the University of Virginia and Yale (Connecticut), Homer rode across the country in the ice car of a train to see the West Coast and, from there, made his way to Europe to study Shakespearean acting.

Fulfilling A Dream

Michael returned to Goldman and told him he was looking for additional opportunities. This, in turn, led to a stint in Switzerland. While there, he befriended a French groom who told him the best place in the world to ride was at Saumur, the French Cavalry School, so after four or five months in Switzerland, Michael found himself at the famous school, enrolled in a two-week course for civilians.

“The course was just superficial; you just got to ride a couple horses a day. Then, from there, I found—I don’t know how I found it, but I made my way to Paul Stecken in Germany, so that was my next big place to ride. One of the boys who was there was Reiner Klimke. He was 21 and already on the German Olympic three-day team. This was a three-day barn, so I got to ride in my first event,” Michael says.

Klimke shared his extensive knowledge of riding theory with Michael, giving him a CliffNotes version of the writings of the best equestrian minds.

As for his transition from equitation to eventing, Michael says, “That’s what everybody did. Where I went, everybody was eventing. They did flatwork, they did show jumping. The cavalry went back to having the great horsemen who became the leaders of the French School, the German School. They did all of it.”

The year after Michael did the two-week course at Saumur, the school decided to allow—for the first time in history—civilians to attend the non-commissioned officers course.

“It was brutal. You rode six horses a day, no irons, and when you got off for lunchtime, you just stood with your hands against the wall. I wore three pairs of underwear,” Michael confesses laughing.

“But it was something that I wanted to do. This was just brutally getting you to have a leg and seat on a horse. All riding, you jumped on from the ground and went out for 1 hour and 15 minutes and came back in at the trot. All trotting. Just trotting, just trotting, just trotting,” he says with a chuckle.

He would do this for three months until the head of Saumur, Col. Margot, uttered words that would once again advance his dream. Michael repeats the words in French before taking pity on my confusion and translating them to English.

“He said, ‘Come here!’ And I said, ‘Yes my colonel,’ and he looked down from the back of the horse he was schooling and said, ‘Starting tomorrow, you ride with the officers.’ That meant that, from that day on, Jack Le Goff became my trainer, and I had seven horses to ride every day, and the French government paid for all my competing!” he exclaims and slaps his knee.

ADVERTISEMENT

Michael Page was one of the first civilians to ride with legendary trainer Jack Le Goff at Saumur and was instrumental in bringing Le Goff to the United States following the 1968 Olympic Games. Herby Wiesenthal Photo

The hours of hard work had paid off, despite Michael needing to visit the infirmary occasionally to recover from such strenuous training.

“You sat on a horse for seven hours a day with no stirrups, and it either broke you, or you learned it. I would go to the infirmary like every three weeks, and you’d spend three days in bed, and they’d give you these big horse pills, and then you’d go back. I remember one time saying, ‘This is great!’ I don’t have to think for a year; all I have to do is polish my boots. You got breeches made in the place; everything was done for you!” he exclaims.

The course was a nine-month commitment. Michael would stay for two years. Call him a glutton for punishment, but he loved it.

With the French government paying for his training, Michael saved enough money to fly his parents over. When I ruminated that his dad must have been proud of him he says, “He was happy if I was happy. It was, ‘You’re fulfilling your dream.’ ”

From Saumur To U.S. Team

Equally proud of the son he never had, Wiesenthal closely followed the progress Michael was making in Europe, which included placing sixth in the military division at the French National Championships at Fontainebleau. (In a box of memorabilia Michael gave me to use for this story, there is an album Wiesenthal made for Michael with 8″ x 10″ black-and-white photos and accompanying typed descriptions of this period of his career.)

Mounted on the fireplace mantel next to Michael’s chair is an oval plaque he received for his achievement.

“My friend, Herby—whenever I would go to a horse trials or an event, he would put a little thing in the Chronicle! You know, in the back? ‘Michael Page was sixth in the military division,’ so it sort of kept the team interested in me and knowing in the back of their mind my name. So I finished at Fontainebleau,” he continues, “And I got a telegram from the USET, and it said, ‘John Galvin has purchased six event horses for his daughter in California, and he wants to sponsor the three-day team. Would you be available to come to California and see if one of the horses would be appropriate?’ ”

As to why they reached out to him, Michael says, “There were very few event riders, and in the Chronicle were all these little snippets. ‘Ah, there is a familiar name! Michael Page! Oh, he won the Medal, and now he’s doing this, two years later. So I got this telegram, and I went home.”

He drove his family’s Jeepster across the country in seven days to Sir John Galvin’s massive ranch in the San Ynez Valley near Santa Barbara. Galvin’s daughter ultimately decided to pursue dressage, yet Galvin offered to sponsor the eventing team.

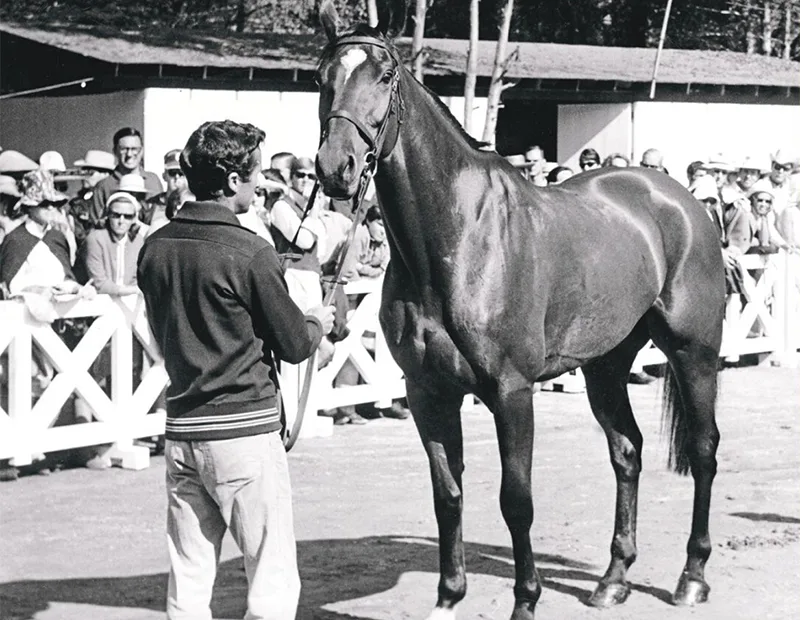

John Galvin purchased numerous event horses, one of which was Grasshopper, whom Page would ride in two Pan American Games and two Olympic Games. Tony Vacekt Photo

“John Galvin was special and unique. He was a real catalyst for eventing. There was not much at that time going on,” Michael says.

At Galvin’s barn, upon his introduction to a 15.1-hand Connemara-Thoroughbred gelding, Michael saw a flash of what he most loved about horses from his childhood: the ability of a horse to create an opportunity to do something unique.

“My first Olympic horse fulfilled my childhood dream. That was Grasshopper,” he says.

Grasshopper had already been to the Stockholm Olympic Games in 1956.

“He was special. The world then was special. You have to realize that then, in those days, the speed and endurance was 22 miles. Took an hour and 45 minutes. You had a first roads and tracks, you had a steeplechase, then you had a second roads and tracks, and then you had the cross-country, then you had the run in,” he says.

“So you needed a tough, strong, fast horse. He had already done an Olympic Games, and he got eliminated for jumping outside a flag, but other than that, he jumped clean. He was a real different horse. He did not especially like people. If you walked up to his stall, he’d come with his mouth wide open. Obviously, since I am light, and he was small, that was the sort of horse I was given. And since I had just come from Saumur, I could sit on anything that stood up. I mean, I could stay on,” he clarifies with a laugh. “I don’t think it meant I rode better than anyone else.”

Jimmy Wofford, a bit younger than Michael and an eventing legend in his own right, remembers the early days of Grasshopper.

“He was called Grasshopper because when Sir John Galvin came to see Michael try him out, he bucked like a son of gun, and Galvin said, ‘Well, if you like him, you’ll ride him, but you know he bucks like a grasshopper!’ But he was a phenomenal creature. At the end of a 22-mile classic Olympic level three-day event, he’d still be pulling,” he says.

“I had seen him go when he was called Copper Coin and ridden in 1956 in the Stockholm Games,” Wofford continues. “So when I went out to watch the Olympic Trials in 1960 at Pebble Beach, I walked into the courtyard at the old Pebble Beach stables, and no one was around, and Grasshopper’s name was on his door. I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just wander in there and take a look at him.’

“I was a little greener in those days. Now I wouldn’t dream of going into someone’s stable with no permission and unannounced,” confesses Wofford with a laugh.

“But I just opened the stall and went in there, and let me tell you, I came out of there a lot faster than I went in! Grasshopper did not tolerate fools easily. He ran me out of there!” he says, still laughing.

Outside The Box Training

The pair had a challenging start, forcing Michael to take an unconventional approach to earning the horse’s respect.

“After 2 1⁄2 weeks of trying to control him, it was getting to the point that I knew I was going to get hurt or he was going to get hurt, and there had to be some way of getting through to him in a way that made him respect me. He was bucking and vicious. It wasn’t in good fun. I was fine, but it took two people to hold him, and someone would throw me on because he wouldn’t stand still,” he says.

Michael Page’s first Olympic partner, Grasshopper was a 15.1-hand half Connemara horse known for his feisty temperament and incredible stamina. Photo Courtesy Of Michael Page

His plan was to use the vast acreage of the Galvin ranch and nearby mountains.

“We didn’t use drugs in those days. We didn’t do anything. It was you against the horse, and he was either going to kill himself or kill me. So I said, ‘What I am going to do is no stirrups because I’m going to have to go through the cattle gate at 90 mph, across the road, and then I’m going to go straight up the shale mountain, and every stride he is going to jump into the shale. He’s only going to be able to do that a short amount of time, and then he’s not going to be able to breathe anymore, so then he’ll stop.’ So we went through—and I mean sparks flying across the road—it was really cool!” he says with a laugh.

Michael had to turn Grasshopper up the mountain three times before he would trot when turned back down.

“But it was not fun,” he says. “There was just no return. There was no return for him and no return for me. So if I could get him to stop breathing, so he couldn’t move, it would give me a chance for him to actually know I was on his back, and I was the one responsible. It wasn’t like I wanted to do this. I needed to do this. It had to be done. I understood that is who he was, so I had to think outside of the box training.”

The message got through, and while Grasshopper remained a challenging horse, the pair would go on to win an individual gold medal at the 1959 Pan American Games in Chicago, with his family there to cheer him on.

“I remember driving in the car with the whole family, and they were just announcing the winner of the three-day event, which was me, and everybody started yelling! It was good. It was a fun thing, although my mother wouldn’t watch. She would stay in the car. She was nervous about me getting hurt,” he says.

Their first trip to the Olympic Games in Rome in 1960 was disappointing when they were eliminated after two falls, which Michael says weren’t the horse’s fault. Following the 1960 Games, Michael was drafted into the Army.

He thrived during his basic training at Fort Dix (New Jersey) and was named a squad leader. He briefly considered making the military a career after receiving special recognition for his leadership qualities and an invitation to attend officer’s training, but he was dissuaded by his father. Homer needn’t have worried, as very soon after, Michael was called to the base office.

“They said they had new orders for me from Washington, D.C. That I had to leave and was assigned to Fort Ord in California to ride the horses six hours a day. I had already done Rome. I lived at a little house next to the stables in Pebble Beach and had six horses to ride every day,” he says.

“We had the big horse trials out there at Pebble Beach, the Wofford Cup, which was a big deal, and I won three times, and it was then retired. So I rode for the Army and was getting paid by the Army!” he says with a laugh.

“I was the last Army Olympic rider, and that started way back in 1936 when the military competed, and there I was, the last. And I always figured that would be a cool picture for the Chronicle,” he says, showing me a photo of him in his Army attire.

“We had the big horse trials out there at Pebble Beach, the Wofford Cup which was a big deal. I won it three times, and it was then retired. So I rode for the Army and was getting paid by the Army. I was the last Army Olympic rider, and that started way back in 1936 when the military competed, and there I was, the last. And I always figured that would be a cool picture for the Chronicle,” says Michael Page. Julian P. Graham Photo

Wofford recalls Michael coming along in the fall of 1958 and suddenly becoming the leading American rider, winner of the national championships. “It’s kind of a chicken and egg—did eventing become more popular and more successful, and Michael showed up? Or did it become more popular and successful because of Michael’s success? Michael was winning medals when none of the Americans could,” he says.

“He was the athlete you wanted to be on the team with because he was always ready; he was always prepared,” Wofford adds. “His horse was always intelligently trained, and especially in those days, in the classic format, his horses were fit. And that was a great deal of success in the classic era, having a horse that had the cardiovascular physical capacity to do that but also to be physically prepared, sound and fit when he got to the competition.”

After the disappointment of the Rome Games the duo redeemed themselves with individual and team gold medals at the 1963 Pan American Games, followed by team silver at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo and fourth individually.

It wasn’t just Michael’s skill with horses that impressed Wofford. It was also his work ethic.

“I’ll tell you a little story. I was a team rookie in the ’60s, and Michael, of course, was the Bruce Davidson or the Michael Jung of his day. I got to Badminton, and I was so excited. There were a couple of riders saying, ‘C’mon Jim! Let’s go down to the pub. It’s Wednesday afternoon, let’s go down and have a few drinks,’ and I said ‘Sure!’ and I walked around the corner, and there was Michael Page, sitting on his tack trunk buffing his boots. And these other guys said to him, ‘Come on Michael, come on. You can do that later, come on down and have a drink with us!’

And Michael looked up and smiled and said, ‘If you look sloppy, you ride sloppy.’ And he went back to shining his boots. I stopped and I said, ‘You guys go ahead; I’ll meet you in a little while,’ ” he says with a laugh.

Michael Page competed at the Pebble Beach, Calif., trials for the 1963 Pan American Games aboard San Jose. Photo Courtesy Of Michael Page

Riding Hiatus

Following the 1964 Olympic Games, Michael stopped riding. It was time for him to reciprocate the support his aging father had always shown him, and he was needed to help run the family business.

The business, which made hat and jewelry box liners, had been in the family for generations. During a visit back to the States from Europe during Homer’s acting career, he met Michael’s mother.

There has always been a bit of discrepancy in the family as to their exact wedding date.

“I think what happened with him—and this is nothing that has ever been discussed—is that he came back from a tour over there and went to work at our company and met my mother, who was working in the factory, right, and I came along,” Michael says with a laugh.

“I mean, no one has ever said anything to me,” he admits. “But that changed the dynamics of his life, and he accepted that and obviously had four more children.”

While he may have stopped riding for the team, Michael served as the chairman of the Selection Committee and as a judge, which he combined with his sales work. He also rode some jumpers.

“I traveled around, and every place I judged, there would be a hat place. I was in sales, and I would do both. It was the right thing to do. My father had made it all possible, and it wasn’t like I was going to stop riding forever,” he says.

Grasshopper likewise retired after the Tokyo Games and went to live on Galvin’s ranch. He colicked and died a year later, which in some ways Michael viewed as a blessing in disguise.

“He wouldn’t have been happy, just being turned out,” he says.

Foster Care

A few years later, in 1966, Michael got a call from the team to take a look at a new horse for a possible return to competition. Foster had made his way to Gladstone and was being cared for by a young groom.

ADVERTISEMENT

Enter Georgette.

Foster was a tricky horse, suffering from a water phobia caused by a fall in a water jump when he was younger.

“Foster was all Georgette. Everything that happened with Foster, happened with Georgette,” Michael says.

This would be the beginning of not only an amazing partnership for Michael and his new mount, but also, more importantly, with the woman who would become his wife.

Michael and Georgette Page met when she was grooming Foster at USET Headquarters in Gladstone, N.J.. Photo Courtesy Of Michael Page

Fun fact: The pair decided to get married after dating for seven years when Michael received an invitation from Queen Elizabeth to Princess Anne’s wedding. It was addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Michael O. Page, and upon showing it to his father, Homer said they should not go unless they were actually married, so off to the courthouse they went.

Michael continued to work at the family business, commuting three hours each way into the city after riding in the pre-dawn hours.

He approached U.S. show jumping coach Bert de Neméthy one day at Gladstone and asked if there was any way to tweak the training schedule and perhaps alternate times with the show jumpers. Michael’s query was not well received.

“I don’t remember the exact words, but it was something along the lines of, ‘This is a waste of my time.’ So I said, ‘You know Bert, the only medal that was won in Tokyo was won by the eventing team, and we deserve a little bit more consideration than you are giving us.’ Smoke was coming out of his ears, and we never spoke again,” he says.

The trio—Georgette, Michael and Foster—would go on to create amazing new memories and share triumphs, most notably team gold and individual bronze in the 1967 Pan American Games and team silver and individual bronze in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

Prior to the 1967 Pan Am Games, Michael recognized that he needed to get a few more miles under Foster’s belt and decided to take him to Badminton.

He prepped for the event with Lars Sederholm at Waterstock Horse Training Centre in England. The two men knew one another from Michael’s time at Saumur, where Lars had been a working student.

“I went and lived in a little caravan, and we went to six horse trials, and Lars was great. We are still great friends. He knew [Foster’s] history of stopping. I said, ‘All I want is somebody smarter than me, helping me figure out how to go.’ Lars said it wasn’t a question of competing for a ribbon, it was a question of getting the horse to have a shot when it counts. So we went to six horse trials, and I just cantered slowly, and wherever the water was, I made like the world had changed and took a double handful [of contact] and finished with him as strong as I could get him,” he explains, once again revealing the delight he found in figuring out tricky horses.

“Then we went to Badminton and jumped around Badminton and were 10th! So that was great. The whole idea was I had to do something that gave us a shot,” he recalls.

Wofford was impressed by Michael’s skills on two vastly different horses (although, interestingly, Grasshopper and Foster shared the same sire, Tudor).

“Foster, and I hate to be rude, but he was not 100 percent genuine, and you would not have known it from the results. I think that displays a lot of range in a rider’s skill set, when they can ride two very, very different horses like that,” Wofford says.

Michael Page knew the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, where he won team silver and individual bronze aboard Foster, would be his finale. Werner Ernst Photo

It’s Better To Die

Another encounter with de Neméthy at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City provided a bit of extra motivation for Michael.

When Michael’s driver to the start box of the cross-country course forgot his keys, they approached de Neméthy, who had just pulled in to watch cross-country with the rest of the show jumping team, and asked for a lift. De Neméthy refused, infuriating Michael.

“So we start off, and Foster is really galloping well, and we’re coming around to the sixth fence, and you can see the stables on the left hand side. All of a sudden I look at his ears, and his ears are saying, ‘Those stables look nice, and I think the jump we are heading for does not look like something I am just going to do easily,’ ” he says with a laugh.

“So in those short seconds, as he starts to go up onto the bank, reluctantly, we are still galloping, but I promise you, it comes into my mind that Bert de Neméthy is going to be really happy if I fall on my head. I said to myself, ‘It is better to die here than have Bert de Neméthy laugh at me having a refusal,’ ” he says.

Michael spurred on Foster. The horse made it over but struck the jump.

“He hit it so hard that when I came in off the cross-country, he had lost both his front shoes. I was down about this high off the ground,” he says, measuring about the distance of a foot with his hand. “And I see his hind end up behind me, and I am going to be squashed dead, and then, at the last moment, I see his right leg come out, and he picked it up and off we went! Because he was such a great physical specimen he was able to recover and get his leg out. But if not for Bert de Neméthy, I never would have said, ‘It’s better to die here than it is for Bert to be happy about me not getting around.’ I wouldn’t have gone to the limit, where you know it’s not going to happen, but I said, ‘F*** it. I am going to do it anyhow.’

“I always wanted to have a place where I could thank Bert for that,” he says.

It was just the finale he’d hoped for, as he knew he’d retire following the 1968 Olympic Games.

“I was on the airplane home when I decided. I had to go back to work. It wasn’t like I was going to stop riding completely, but I was going to stop event riding,” he says.

The U.S. team of (from left) Kevin Freeman, Michael Page, Mike Plumb and Jimmy Wofford earned the silver medal at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Steve Price Photo

So was it hard for him to walk away?

“No. Are you kidding? Did you hear how Mexico went? How could that be hard to walk away from? I didn’t ride because I wanted to be an eventer. I rode because I loved to ride!” he says.

Another Type Of Legacy

In addition to Page’s success (and near catastrophe) in Mexico City, another legacy was born during those days south of the border. A longtime friend from his days at Saumur, Le Goff approached him about the possibility of coming to work in the United States.

Knowing that the temporary U.S. coach Maj. Lynch was leaving for the Morven Park Equestrian Institute (Virginia), Michael set up an appointment with U.S. Equestrian Team President Whitney Stone and suggested he take a look at Le Goff for the position.

Stone, who had already planned on being in France to watch a horse he owned run in the Prix de l’Arc Triomphe, met with Le Goff in Paris.

“About a month later, I got a call from Mr. Stone’s office saying Jack Le Goff would be coming over on a trial basis, and the rest, as they say, is history,” says Michael.

Le Goff would coach the team for the next 12 years, and upon his retirement, Michael received yet another call from Gladstone, this time asking if he would be interested in the chef d’equipe position.

“I said, ‘Woah, that sounds like a good thing to do, to get back into it,’ ” he says. He would hold the job for two Olympic Games, two Pan American Games and two World Championships, from 1986-1992. Despite many good riders and horses, the team found little success, and I get the impression these years weren’t a highlight for Michael as he diplomatically says, “It was an interesting few years.”

Wofford explains that Michael was “a part-time chef d’equipe in a sport that had become professional. The International Olympic Committee changed the rules. They opened the Games in 1985, and we were a little slow to respond to that. At that time, Jack Le Goff retired in 1984. The riders did not want a coach. Jack was a very, very domineering, authoritative coach, and the riders were a little tired of that. They didn’t want any coaching, and so we went through a dry spell, and unfortunately, Michael was the chef d’equipe then. As I said, he was fully employed, plus he was running a program, a riding and training program, and trying to be chef d’equipe, and I don’t think it worked out very well.”

It Was Never Not Horses

Michael continued to ride and train jumpers and for seven years with Georgette’s help, he ran Old Salem in addition to commuting to the city and running the family business. He’s held numerous committee roles within the national governing body, including as the chairman of the Equitation Committee, and he’s judged seven ASPCA Maclay Finals.

In that role, his emphasis was always on the rider and horsemanship abilities. He became known for making riders mount and dismount. Sounds simple, right? But it was a skill many riders did not possess.

“From my background, I always wanted the playing field to be as level as it could, which meant in a horsemanship class, it should also count that the child’s ability should have more of an impact and not because of who she rode with or the horse she has. So in my last years, what I used to do in all the open flat classes, I had them dismount and mount. That was a big deal. I remember five kids couldn’t get on their horses and had to walk out of the ring,” he recalls.

“They got leg ups, etc. The fundamentals of horsemanship many didn’t have, and I don’t agree with it from an education point of view,” he says.

While judging and committee work (along with his day job) kept him busy, his passion for riding continued.

“It was never not horses. I used to commute to the city, and when I ran Old Salem, one year I had three Olympic trials there. I called Frank Chapot, we got the Empire State Grand Prix going and hosted eventers and dressage. I just channeled my passion for riding in a different manner. I kept showing in the jumpers, and then I started riding at Kent [a boarding school an hour from them]. It’s been great. I’ve had five grand prix horses there,” he says.

Michael Page is retiring from his role as riding director after 28 years with Kent School in Kent, Conn. ESI Photo

For five years he rode a show jumper named Show Man. “I would show him with no stirrups,” Michael says. “I’d do 1.40-meters with no stirrups, but if you ride without stirrups you sit tight, and you are stronger, and your horse goes forward better. I mean, you can’t be competitive, but I was never interested in being competitive. I just wanted to ride.”

He’s been resident trainer and instructor at the Kent School (Conn.) for 23 years and rides there seven days a week.

Looking back, does he have any regrets?

“I am just so happy I did what I did and still am riding. We are very lucky,” he says, and he becomes a bit serious for the first time and pauses.

“I am not afraid of dying,” he concludes after a moment, recognizing he has had an extraordinary life.

For Michael, every box has been checked, including many, such as his induction into the U.S. Eventing Association Hall of Fame in 2006, he never could have imagined as a child watching television shows about the Pony Express.

“I was extraordinarily happy that my horses had been good enough to get me there,” he says. “Do you hear me? That is really true. I think one of my greatest things was I wanted to be a Pony Express rider, and when Grasshopper, after 22 miles, ran away with me, even with two falls, I thought, ‘Holy sh**! I’ve done my Pony Express ride! I am still alive!’

“Then about 10 years ago, there was a little girl riding with me, and she knew who I was,” he adds. “She gave me a little plaque, and it said, ‘It was never about the ribbon. It was about the ride and the horse that got me there.’ ”

For Michael Page, it’s always been the ride that counts.

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our July 10 & 17, 2017, issue. Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.