When Jim Koford, a Grand Prix rider and trainer, received the $25,000 Anne L. Barlow Ramsay Annual Grant from The Dressage Foundation to take his 10-year-old Dutch Warmblood Rhett to Germany for training, he expected it would improve his riding.

He didn’t necessarily expect it would change his life.

Koford, 47, spent three months riding with Michael Klimke, moving from client to employee during that time. Now he’s headed back across the pond with Rhett to take a permanent position with Klimke.

“I’m loading up my stuff and letting myself be a student and grow as a rider and a trainer and seeing where it takes me, and takes Rhett,” Koford said. “It’s very exciting for me personally and professionally, and I’m sure it’ll be quite humbling.”

He Changed Everything

It wasn’t Koford’s goal to be a dressage professional. He grew up in Pennsylvania, doing Pony Club, eventing, dressage, hunters, equitation and whatever else he could manage. He went to college at Wake Forest University (N.C.) and got a job in advertising at Equus magazine. For nine years he worked there and rode dressage on the side, taking an off-the-track Quarter Horse up through fourth level.

But it wasn’t quite enough, and Koford was frustrated with the lack of energy he’d have after leaving the office.

“You work long days, and at the end of the day you walk into the barn and it’s dark and it’s cold and you’re thinking, ‘Now I’m trying to make the most important part of my day.’ And you just don’t feel like you can give your best at the most important thing,” said Koford.

After he’d taken the Quarter Horse as far as he could, Koford was hungry for more. He found a classified ad in the Chronicle looking for someone to ride a pinto Dutch Warmblood stallion and gave the owner, Elizabeth Potter-Hall, a call. He got the gig, but he didn’t quit his day job. But once Art Deco (Samber—Zorba) started doing the FEI-level classes, he realized he might have to.

“I reached a point in my career where I was at a junction, where I had to become more serious about the riding,” Koford said. “Art Deco was showing Interme-diaire I, and you can read all the books you want about piaffe and passage, but by myself, I just didn’t know how I was going to proceed from there.

“I told myself all along, ‘I’m not going to quit a career because of horses.’ That just didn’t make sense,” he added. “But I did it anyway.”

Koford worked with Steven Wolgemuth for a year, getting Art Deco to Grand Prix, and then eventually branched out into his own teaching and training business. But he made a deal with himself: If he was still living on peanut butter and jelly and barely scraping by financially two years later, he would return to an office.

He’s still in the barn.

“I never looked back,” Koford said. “I never went back into an office. I think I’ve worn a suit a couple of times since that day. It’s amazing how things just sort of snowballed from there. It’s been a fun trip.”

Dressage For The Masses

Though Koford has now trained eight horses to the Grand Prix level, his students will say his greatest strength lies in teaching horsemanship and in taking unconventional horses to levels others said they wouldn’t reach.

Kathy Rowse, Suffolk, Va., is a Grand Prix trainer and USDF S-rated judge who started riding with Koford 15 years ago.

“When I first started riding with him, he had the ones that were problematic for other trainers,” Rowse said. “They came to him, and he would turn them around. He still does that. Jim, in this sport that’s become extremely expensive, has always done dressage for the masses. He taught anyone—any age, any breed—and he moved them along.”

Rebecca Vick, 29, started riding with Koford when she was 17, and he’s remained her primary trainer since then.

“He was so gracious and kind and wonderful with the horses,” said Vick. “I’d never seen people get out of horses what he was able to get out of the horses. He was so positive and so very much about making things work for each horse.”

Vick moved to Southern Pines, N.C., and worked for Koford for more than six years. She moved from riding first level to Grand Prix during that time. Now she has a teaching and training business in the Southern Pines area.

“If he can turn me into a Grand Prix rider he can turn anyone into one,” Vick joked.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The coolest thing about working for Jim, because I’ve worked for other people too, is that he was so willing to roll with anything that came our way. It made it a really comfortable work environment. I’ve also never had so much fun working for someone.”

She also echoed Rowse’s statements about Koford’s adaptability.

“He taught me to work with a lot of different types of horses,” Vick added. “I never heard him say, ‘This one can’t do it.’ He’s so willing to work with everything. He taught me so much empathy for the horses—he’s always giving them kisses on the nose and hugging them.”

Ill Advised On So Many Levels

Koford started teaching dressage and taking horses in training, first in Northern Virginia and then later in Southern Pines and Raleigh, N.C. But his life took an unexpected turn when he took a trip to England a few years after quitting his advertising job. He attended the Badminton CCI**** (England) as a spectator and then went on a week-long cross-country riding vacation. He had an unexpected urge to take up eventing.

“I decided it was just a piece of me that I couldn’t let go,” Koford said. “I didn’t want to just circle in a dressage ring anymore.”

Though he’d evented as a teenager, riding through preliminary level, Koford hadn’t jumped in years. After returning to the United States, he purchased an advanced horse, a Thoroughbred named Bank On It, and took him as far as the Rolex Kentucky CCI*** in 1996.

After Bank On It was kicked in the pasture, Koford found Max Motoring, a bolter and a reject from Bruce Davidson and David O’Connor’s barns, and started competing him. Thanks to the horse’s temperament and lack of dressage schooling, they weren’t competitive at the bigger events but Koford, with his background, hoped the dressage might be improved eventually.

“This horse was crazy, and his dressage was horrific. And I was like, ‘Maybe I can fix his dressage, maybe I can’t.’ But this is what I did for fun. Most of the time I would be ‘Dressage Professional Jim,’ and I kept my life very compartmentalized,” he said.

Koford was so successful at compartmentalizing, sneaking off to events when he had a spare weekend, that none of his students or clients even knew he was entered in the 2000 Rolex Kentucky CCI**** until the Chronicle Rolex Preview Issue came out, with Jim Wofford calling Max Motoring “one of the more difficult rides in the field.”

“I would tell some people I was going to an event, but I think they thought I was riding novice or something,” he said with a laugh. “I went to a dressage show after the Rolex Preview issue came out, and there was this picture of me galloping on Max Motoring in it, and they were like, ‘What are you doing? Why are you doing this?’ ”

Max Motoring and Koford ran around Rolex with only time faults on cross-country day, but the horse grabbeda heel during his run and Koford withdrew him from show jumping before the jog. It turned out to be his last event with Max—he was in a trailer accident on the way home from Kentucky and never returned to the advanced level. Though Koford had contemplated the Burghley CCI****, he decided he was finished with eventing.

“It was time to close that chapter,” he said. “I’d really done everything I wanted to do in eventing, and I realized that. It was just a funny, good time. I look back now, and I shudder because it’s not like I went and took jumping lessons and thought, ‘Oh, I need to study how to do this right.’ It was just sort of riding from the seat of my pants.

“It was so ill advised on so many levels,” Koford continued, smiling. “But I had this sort of notion in my head, ‘If you can ride a horse straight and balanced and in front of the leg, you can jump any fence in the world.’ That was sort of my mantra. I had a very, very bold horse, and we managed to get the job done OK.”

Pedal To The Metal

After Art Deco and his foray into eventing, Koford focused on bringing horses up through the levels and teaching students to do the same.

His next big mount, Donatelli II, a black Oldenburg stallion by Donnerhall, was ranked 11th in the U.S. Dressage Federation national standings at the Grand Prix level. But Donatelli contracted EPM, and Koford sold him to a hunter barn for a less physically demanding career. He competed Maryanna Haymon’s Hanoverian stallion

Don Principe successfully through the Grand Prix level before the horse moved on to Courtney Dye’s barn last year.

“I never really had one horse,” Koford said. “At the end of the day, I was so thrilled to have a career as a dressage professional. I enjoyed competing and I enjoyed making the horse as good as it could be and challenging myself, but if I got an offer it was never a question as what my responsibilities had to be. That is changing a bit now.”

The change is due to Koford’s current mount, Rhett. In 2007, his friend Rebecca Langwost-Barlow called him about a horse she was riding at third level. The horse, according to Langwost-Barlow, was a little strong for a woman but still needed a sensitive ride, as he was quite spooky and insecure.

“I had just sold Donatelli II and had Don Principe really coming up the levels, and he was looking promising,” Koford said. “As far as my own horse, I wanted something completely different. Donatelli was little and had a cob-sized bridle, just a tiny, refined little sports car. When my friend called about this horse, and I went to see him, I just couldn’t believe my eyes. He was 17.2, a big head, big feet, long back and I was staring like, ‘Oh my gosh. I know I said I wanted the opposite, but this is ridiculous.’ ”

After his first ride on Rhett (R. Johnson—Madette), Koford found himself slightly underwhelmed. But weeks later, he found he was still thinking about the horse. When he went back to Langwost-Barlow’s for a clinic, he said if the horse loaded in his horse van he would take him home to North Carolina.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He just followed me right up the ramp and backed in, and I said, ‘All right, we’re going home.’ It’s been quite an adventure,” Koford said. “He’s funny and silly and hot and goofy and spooky—quite unconventional at times and just pedal to the metal all the time.”

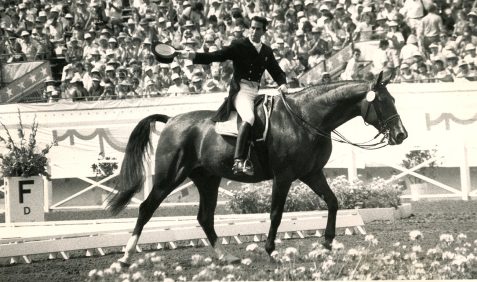

In their first season together, Koford and Rhett finished seventh in the USEF Developing Horse National Cham-pionships (Ill.), and Rhett was the highest-placed American-bred horse. It was that unanticipated success that made Koford consider filling out an application for The Dressage Foundation’s $25,000 Anne L. Barlow Ramsay Annual Grant, given to an American-bred horse for training abroad.

“I’ve always wanted to compete in Europe,” he said. “The pressure of a team would make it so you can’t necessarily enjoy the experience. I just wanted to really train.

I couldn’t believe it when I got the phone call that I’d gotten the nod in and that it was to go to Europe. It was really sort of an amazing opportunity and one that was ultimately extremely life changing.”

A Slow Process

Koford arrived at Klimke’s barn in Muenster, Germany, enthusiastic and ready to learn, but the first lesson he did learn was a startling one: He needed to entirely alter his style of riding.

“My horse was so hot and spooky, every instinct always said, back off, give him a pat, take it easy,” Koford said. “I had to learn to ride forward, and for the first six weeks I was shaking my head, like, ‘I have really screwed up. I can’t do this.’

“It was a tremendous experience,” Koford added. “I’ve worked with many terrific clinicians through the years, and I have to say that there’s such a difference between taking a lesson and living a lesson. You go to a clinic and learn new techniques or feel a new feel, but there’s nothing like daily scrutiny under someone so discerning.

To actually change your go-to feel, it’s a painstakingly slow process.”

The day of their first show in Europe was windy and cold, and Rhett came unglued in the unfamiliar atmosphere. The pair finished last—by a lot. It was another crucial lesson for Koford.

“Your instructor can tell you over and over that your horse has submission issues, but it takes something like that to see it,” he said. “Do you absolutely, unconditionally, have a half-halt? Do you get the correct response from your aids every time, under any condition? Every time after that was better.”

After staying three months instead of the two he’d planned, Koford returned home to train horses and dozens of students. He helped them prepare for regional championships and winter events in Florida, but his experiences in Europe stuck with him. He found it difficult to create the same feeling he’d had with Rhett in Germany once he was home in North Carolina and even once he was in Wellington, Fla., for the winter. The horse was nearly ready for the Grand Prix test, and Koford felt like he’d left Klimke in the middle of a semester.

“I would go into the ring with my horse and try to re-create the magic, and I felt like my left arm was cut off,” he said. “I just felt like I had so much unfinished business.”

Klimke gave a clinic in Wellington in February and had some harsh words for Koford when he was there. He also offered him a job.

“He sat me down, and for an hour-and-a-half he lectured me,” Koford said. “He said, ‘You’re old. This is it. This is your last shot if you want any shot of being an international rider. You’ve got a good horse; you’re a good rider. The only way you’re going to get out of this comfort zone you live in is to go over there and compete with the top riders.’ That made sense.”

Koford has tried to prepare his students for his ab-sence as much as possible and plans to return for clinics every few months.

“It’s difficult to leave a career and a business I’ve deve-loped for 20 years,” he said. “It’s hard to walk away from, but I feel like the sport has grown enough that there are many good professionals I can refer my students to.”

And while Koford’s students are going to miss him, they’re also hopeful about his future opportunities.

“The only thing I can say about him moving to Germany is that he’s helped so many people achieve their dreams, I hope he can achieve his,” said Rowse.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to read more like it, consider subscribing. “Jim Koford’s Career With Horses Has Been A Fun Ride” ran in the June 4 issue. Check out the table of contents to see what great stories are in the magazine this week.