Ingrid Klimke never stopped radiating positive energy from the center of the grand prix arena over the course of her two-day clinic, held Dec. 2-3 at Galway Downs in Temecula, California. The German Olympian and Reitmeister, a multi-talented athlete who has represented her country in both eventing and dressage, coached seven groups of dressage riders on horses ranging from a 5-year-old stallion to those practicing the piaffe, and then she switched gears to guide three advanced eventers through cavaletti exercises. Or, rather, she didn’t really switch gears at all. That’s the Ingrid Klimke way of training: Regardless of the rider or horse she’s working with, no matter what level or which discipline they rode, she met each with the same whole-bodied delight, especially when something clicked.

Klimke was a teacher in constant motion. At one point, she bounded around the ring on foot to demonstrate a change of direction in half-pass. She removed a lot of whips and spurs. She had several riders drop their stirrups. Most, if not all, of these changes were in the name of getting a more “positive” movement out of the combination.

“Ride positively forward!” she would call out, and when she said it, there was a noticeable shift in the way of going for horse and rider: shoulders relaxed, spines straightened, strides opened, necks grew longer.

Riding positively is at the core of Klimke’s philosophy and, as she wrote in her book, “Training Horses the Ingrid Klimke Way: An Olympic Medalist’s Winning Methods for a Joyful Riding Partnership,” the key to her long and storied career in multiple disciplines. Riding positively, to Klimke, means bringing out the best in every ride and having a joyful relationship with your equine partner.

During her clinic, 700-plus attendees got to witness how positive energy translates to movement and learned how to ride positively in practice.

The Warm-Up Sets The Tone

In a session focused on warming up horses with riders Joey Emmert Evans on her mare Khaleesi and Ellie Hardesty on the U.S.-bred Hanoverian Barrington, Klimke emphasized the importance of taking 10-15 minutes at the walk to get your horse to open its body and stretch before asking for any collection.

“My aim is the nose on the ground in warm-up,” Klimke said. “The goal should be the horse chewing the bit out of your hands.”

At the walk, she had both riders take their horses over a set of four cavaletti on the lowest setting, spaced 1 meter apart, letting the horses first look and take their time stepping through the poles. When Emmert Evans’ horse was a bit skeptical of the series of poles, instead of pushing her through it, Klimke reduced the exercise to one pole, then added more as the mare got more comfortable with the question.

Once both horses were swinging naturally on a more open walk step, the cavaletti were widened to 1.5 meters for a trot exercise. Again, Klimke was looking for balance and stretch.

“They should not be running,” she coached. “The hind legs need to be overstepping. Keep your posting smooth.”

To encourage suppleness and rhythm, she had the pairs do serpentines while continuing to stretch, then asked for a working trot, looking for hind-end engagement. After a walk break, they worked on the canter. She encouraged the riders to ride light and forward, almost in two-point, for the first few minutes of canter work.

“As riders we should give our horses courage and confidence. The warm-up is the most important part of the ride; it will set the [positive] tone.”

Ingrid Klimke

“Get in a light seat when you canter, so they can open up without weight on their back,” said Klimke.

Finally, Klimke had the riders ask for soft downward transitions, keeping their horses as straight and relaxed as possible. “As riders we should give our horses courage and confidence,” Klimke said. “The warm-up is the most important part of the ride; it will set the [positive] tone.”

Cavaletti Exercises For Every Level

As the co-author of “Cavalletti For Dressage And Jumping,” which she wrote with her father, German dressage legend Dr. Reiner Klimke, it is perhaps no surprise that Ingrid incorporated the gymnastics in every group and level she taught. From the warm-up on, she used cavaletti exercises to demonstrate how to increase strength and suppleness without compromising the horses’ natural gaits.

For example, when working with Joseph Newcomb on Free Solo EDI, a 5-year old Westphalian stallion, and Marie Medosi on Favorite Song PS, a 3-year-old Oldenburg stallion, Ingrid set up an uneven distance over the cavaletti at the walk and trot by removing one of the poles from the middle of the set of four. The exercise helps young horses maintain their balance over uneven ground and builds their confidence in carrying themselves. It’s an exercise she starts all young horses over, no matter the discipline they are destined for, she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

At first both horses both tripped over the cavaletti. (“These two really are dressage horses,” Ingrid said with an unfazed chuckle.)

She encouraged the riders to be confident as well. Mistakes are part of learning, especially for young horses, she explained. She had the riders maintain soft contact by holding their hands together at the withers, keeping the rhythm with seat and legs and giving through their elbows.

“Some get it right away, but be patient with the ones that take a little longer, because once they get it, you will be rewarded,” she said of training young horses.

Similarly, when she was working with Tokyo team silver medalist Sabine Schut-Kery and clinic organizer Kelly Artz on third-level movements, their first exercise was a rising trot over four cavaletti set 1.5 meters apart. Rather than trotting, both horses tried to jump through the poles, so Ingrid simplified the task to one pole, then two, then three, and finally, the full set.

“Are you sure these horses aren’t eventers?” she joked.

The more the riders moved in harmony with their horses by following with their hands, the more the horses relaxed over the poles. To get her horse to open its stride, she asked Artz to rise on a quicker tempo, and she had Schut-Kery concentrate on getting her horse to lift his poll using the half halt.

In another instance, she arranged the cavaletti on a circle and asked Schut-Kery and Artz to collect their horses into a working trot. First, she had the horses trot around the cavaletti to familiarize them with the shape, then moved them into the exercise, letting each horse make mistakes until they trotted through the curve of poles with consistent rhythm and, importantly, positivity: energy that flowed from the hind end forward. She emphasized straightness and forward motion at every opportunity, which she explained was to help establish suppleness through the ribcage and lateral bend in preparation for more advanced work.

Finding—And Guiding—Positivity

Finding and harnessing positivity was the core of the lesson when Ingrid worked with Caroline Hoffman and Bugei VDOS, a 10-year-old PRE gelding, and Josephine Hinnemann, 17, on the 14-year-old Hanoverian Copa Cabana. The two horses started at opposite ends of the forward-thinking spectrum, and Ingrid relished the challenge of bringing both partnerships to a more harmonious place.

Ingrid had each pair do a walk-trot exercise on a circle in which they trotted, walked for one step, then went back to trot. She was looking for them to keep the energy moving forward and the hind end engaged.

Hinnemann’s seasoned schoolmaster tended to be on the lazier side. Ingrid lovingly referred to him as “the good professor,” and worked with Hinnemann to get him to move more positively from the halt into every gait.

“When you ask him to trot, he should really trot!” She called out. Same at the canter: “Make him gallop, let him run. As long as he has energy!”

Once Hinnemann’s horse was moving forward, Ingrid coached the teen rider to “keep that positive energy.”

On the other hand, Hoffman’s much hotter horse responded over-eagerly in the exercise, cantering from a halt when asked for a trot. Klimke had Hoffman ride without her whip, soften the halt and generally worked on relaxation so that the pair wasn’t overdelivering to their detriment.

In another instance, Klimke noticed that McKenzie Milburn’s Oldenburg gelding, Zero Branco, with whom she is currently competing in the Intermediaire 2 and U25 Grand Prix, was giving her more of a passage than a working trot. She worked with Milburn to achieve a more fluid rhythm.

“Half-halt and give,” she repeated. “More positive forward, give with your hands, longer neck, nose forward. Make it a really smooth movement before we can do the half-pass. Make it easier for him: Give, give, give.”

Lose The Stirrups To Find The Answer

“I often drop my stirrups if there is a problem, because I want to be closer to my horse,” the double Olympic gold medalist said, right before she asked Joseph Newcomb to ride without his. “I want to be able to feel what I’m doing so that I can change it.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“I often drop my stirrups if there is a problem, because I want to be closer to my horse. I want to be able to feel what I’m doing so that I can change it.”

Ingrid Klimke

Newcomb’s young horse kept cantering when asked for the trot, so Ingrid wanted Newcomb to adjust his leg position and encourage him to ride more from his seat. She also had him approach a cavaletti exercise at a trot and transition to a walk a few strides before the poles to encourage the horse to give a different answer.

“If the horse gives an answer, that’s progress, even if it’s the wrong answer. If he gives the wrong answer, you must change the question,” she said.

When USDF gold medalist Amelia Newcomb and her horse, Harvard, were practicing their tempi changes, Ingrid had her drop her irons so that she sat deeper in the saddle during the changes and relied less on leverage from her stirrups. “Yes, you can keep your leg forward, like that,” Ingrid encouraged. “No spur, only squeeze with your calves. Super!”

Likewise, when the upper-level pair practiced the passage and the piaffe, Ingrid called for her to release the horse’s nose and ride with more free-flowing energy. Even in the piaffe, which looks like the horse is marching in place, Ingrid maintained that the movement should be positive and forward. “The horse should be jumping out of each step,” she said.

‘Jumping’ For Eventers

In one of the most anticipated sessions of the clinic, upper-level eventers Chloe Smyth on the Holsteiner Top Quirada, Grace Walker on Oldenburg Frantz EDI and Taren Hoffos on the Oldenburg mare Regalla had their chance to work with the much-decorated German eventer. Her excitement let the audience know Ingrid had been looking forward to this as much as the riders were.

“People ask me when I’m going to give up eventing for pure dressage, and I never will,” she said.

The eventers were in jumping saddles and started by cantering over cavaletti on a circle, with the goal of keeping a consistent rhythm over the rails.

“Maintain a dressage canter over the poles,” Ingrid said. When Walker’s horse got a bit big and off balance, Ingrid asked for more bend to keep him supple.

The next exercise was to establish adjustability without losing positive forward motion. The pairs cantered a straight line between two cavaletti, counting the strides on their first pass. Smyth’s mare got five strides on her first go, then they tried to adjust for six, then an easy five. Ingrid coached her to influence the lead that the mare landed on by putting weight in her outside leg. In the end, they executed a rhythmic six and landed on the correct lead.

Walker’s horse did their first line in an exuberant five—“He was trying for four,” Ingrid noted—but Walker brought him easily back to six and then seven and even managed to squeeze in eight strides. Then, at the end, Ingrid encouraged her to open and go for the four, which they accomplished to a round of applause.

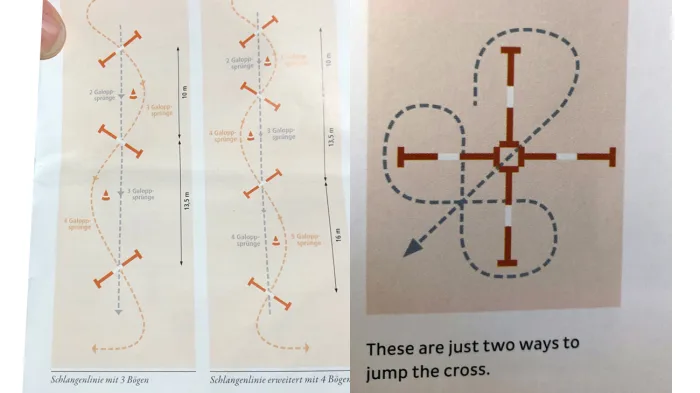

To work on flying lead changes and overall agility, Ingrid set up three- and four-loop serpentines with cavaletti placed on the centerline. She wanted each pair to execute a clean lead change over the cavaletti.

She wanted Hoffos to sit back and not get too light, to help Regalla keep her balance.

“Keep her in a dressage canter,” she said. “Use your weight aids and stay in a dressage position.” When she was asking for changes, Klimke wanted to see a really round serpentine. Then, to practice accuracy, she had the riders take the straightest distance, over the center of the poles.

Walker’s horse needed a bit of encouragement to make the changes, so Ingrid asked her to give the aids the stride before the obstacle. They practiced until they got it.

A final exercise asked the riders to practice rollbacks at the canter over four cavaletti situated like a giant cross. Ingrid started by having each team ride a figure-eight over two of the four elements in the form of two 10-meter circles. Then, she asked for smaller and smaller circles until the riders were almost making a quarter pirouette. Everyone was asked to sit deeper and give more quickly to keep their horses balanced and turning on the hind end.

“To win a jump-off, you don’t ride faster, you make tighter turns,” Klimke noted.

When asked after the clinic why she thought that so many riders had to be reminded to give to their horses to create and sustain positive energy, Ingrid shrugged and said with a smile, “It’s something that we all have to be reminded of, all the time.”