Jill Henneberg had a fairytale career with the mare who took her from her first event to the Olympics.

Before Jill Henneberg ever competed in eventing, she participated, along with her family, in another kind of competition—boat racing. The Hennebergs, of Medford, N.J., called their small sailboat Nirvana.

“It wasn’t fancy, but it beat almost all the fancy boats in every race,” recalled Henneberg.

So when she finally received her first horse, at the age of 13, she knew exactly what she’d call her.

That first horse was just what every trainer tells their young, inexperienced students to avoid—a 3-year-old, off-the-track, Thoroughbred mare. The owner needed to pay back board and sold the mare for $600. Her barn name became “Cheapers.”

“It comes down to luck more than anything,” said Henneberg. “I wanted four legs and a tail, and my parents thought the price was good.”

Cheapers hadn’t been ridden since her last race a few months earlier, but Henneberg, fortunately, was a fearless child. “You couldn’t get on her from the ground, but she was pretty darn good, considering,” she said with a laugh.

Until she received her driver’s license four years later, Henneberg rode her bike the 12 miles from her home to the barn each day. “I was totally obsessed with having a horse, and there wasn’t a day I wasn’t out there,” she said. “I had lessons once a week and worked hard on what I learned in between.”

When she was 4, Nirvana began jumping, and at the pair’s first event, in the crossrail, “chicken little” division, they won.

But Henneberg’s trainer at the time told her that the 16-hand, gray mare would be limited. “I was so attached to her that I wasn’t going to hear any of it,” said Henneberg, who persevered through several stops and falls at the novice level.

When Nirvana was 6, and competing at the training level, Henneberg got her first glimpse of her mare’s talent. She was working and training with Jane Cory at Pleasant Hollow Farm in Coopersburg, Pa., and Cory took Henneberg for a lesson with Bruce Davidson.

“I was a kid, and I just thought that was the coolest thing I’d ever heard of,” said Henneberg of her lesson with Davidson.

“Bruce sent me out over some preliminary and intermediate jumps, and the bigger the jumps got, the better she went,” she said. “Bruce and Jane said she was a pretty darn good jumper, and she went prelim not long after that.”

No Looking Back

In 1991, Henneberg was training with Debbie Adams and completed her first three-day at North Georgia in the Harry T. Peters young rider division. In 1992, she completed the young riders one-star at Essex (N.J.),

finishing fourth and earning best conditioned.

“She wasn’t incredibly easy on the flat. She stuck her tongue out in dressage, which was very hard to get past. But there were very few events where she didn’t come home with a ribbon,” said Henneberg.

But by the time the pair reached the intermediate level, a love of cross-country had been born, and they only completed three intermediate events—winning a young riders division at Fair Hill (Md.)—before moving up to advanced, now under the tutelage of her Area II young riders coach, Michael Godfrey.

“Something just clicked, and the mare became this complete and total machine,” said Henneberg.

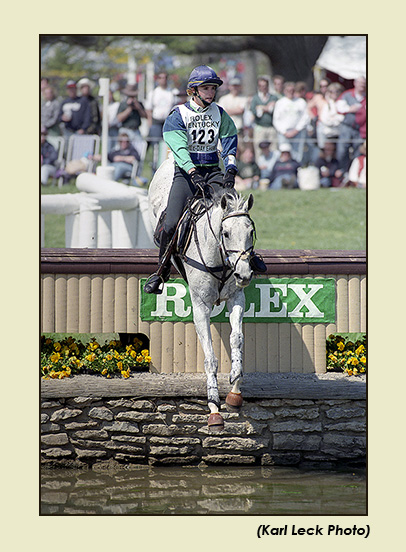

They finished second at the advanced horse trials held at Rolex Kentucky in 1993 and completed the Fair Hill CCI*** (Md.) that fall, earning the Markham Trophy as the top young rider.

In 1994, they competed at the Rolex Kentucky CCI***, finishing eighth and earning the best conditioned trophy.

“Rolex had been my biggest dream,” said Henneberg. “I’d gone as a kid and watched, and it is an experience like none other. If you experience it ever once in your life, you’re lucky.”

Henneberg was just enjoying the ride as much as her mare. “Every jump, she’d give 110 percent and completely take care of me and herself,” she said. “She had this love of cross-country, with her ears pricked the whole time, thinking, ‘Where’s the next jump, mom? This is cool!’ She was a speedy little thing and never struggled. She was always under the time, still pulling me through the finish flags.”

The selectors considered the pair for the 1994 World Equestrian Games, but Henneberg knew it was more than a long shot for a 19-year-old, inexperienced rider. “I knew I wasn’t going, but it was pretty cool to be considered,” she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Bumps In The Road

But by the fall of 1994, Nirvana was sidelined with a fractured splint bone. “I made the decision to have it removed,” said Henneberg. “I was told it would be a shorter recovery, but I could not get her sound.”

Nirvana sat out most of the fall season in 1994, and 1995 seemed to be going the same way. Although she was short-listed for the 1995 Pan American Games, Henneberg couldn’t get the mare 100 percent right.

“It was pretty heartbreaking to make the call to [U.S. Equestrian Team director of eventing] Jim Wolf, to pull her from the list because she wasn’t sound,” said Henneberg.

Then, said Henneberg, Dr. Brendan Furlong came to the rescue. “He said, ‘I think I can help you with this problem and get your horse back,’ ” she said. “Three weeks later she was sound.”

In 1996, they were back on track to Rolex Kentucky, where they finished 10th and Henneberg anxiously awaited the announcement of the Olympic shortlist.

“I remember it feeling like a million years after Rolex to find out about the short list,” she said. “It took a while to process that I was a legitimate contender. I was there with people I’d been watching since I was a kid, and basically, I still was—I was 21.”

A final selection trial was held at North Georgia, and Henneberg vividly recalled the moment she learned she was on the team. “They sat us on a grassy area, and I remember it being a very intense situation,” she said. “There were 21 people on the short list, so you had 21 riders sitting around waiting to hear just a few names. I remember my mind going blank [when my name was announced] and thinking, ‘Did I just hear that?’ It was a very surreal experience.

“There’s nothing like the experience of calling your parents and saying, ‘I’m going to the Olympics!’ ”

The U.S. team shipped to a farm in Georgia for two weeks of training, and Henneberg and her mare did nothing but dressage, under the watchful eye of team coach Capt. Mark Phillips, the entire time.

“Mark Phillips was pretty bound and determined for the mare to put in a competitive test,” said Henneberg. “He was tremendous with her. I’d warned him she could take about 20 minutes of flatwork a day. In those 20 minutes, we did everything we needed to accomplish, then I went off on a trot set on a loopy rein.”

By the time they circled the arena in Atlanta, Henneberg was able to breathe a sigh of relief. “She’s so telltale about how she’s going to be, and I remember thinking, ‘Thank you—today is a really good time to decide to put your head down and be a good girl.’ ”

They scored in the 50s (under a different scoring system than is currently used). “For that mare, it was incredible,” said Henneberg. “I was really excited.”

But Henneberg’s cross-country performance became the most memorable part of her Olympic experience. A hard, infamous fall at the Olde Town Ponds water complex at fence 13 ended her round.

“I’ve watched that video 4,000 times,” said Henneberg with a laugh. “Because of the time of day, the sun had shifted, and the house over the bridge was casting ashadow over the jump. The mare thought the shadow was part of the jump, and she leaves way too early for the bank.”

Both Henneberg and her horse walked away from the incident, Henneberg having hit her head pretty hard, but the greatest damage came from the criticism she received from the public.

“It was very difficult, being 21 and having the kind of criticism I had from the amateur community,” she said. “The NBC coverage made it look like I didn’t care what Mark [Phillips] said, and that was absolutely not the case. I was given 100 percent permission to go that [fast] way.

“The decision to go that way was based on the experience I’d had with that mare and the striding in the one-stride versus the shortness of the bounce,” she added. “I was fairly well crucified for that, but I was a pretty darn tough kid.”

Over Too Soon

Henneberg moved on from that incident by taking aim on the world’s most prestigious four-star event, in England. “I was excited to go overseas, and I very much believed I had a Badminton horse,” she said.

But as fortune would have it, she was never able to find out. In her first event of 1997, Henneberg ran the intermediate at Rocking Horse (Fla.), and Nirvana came off the course with a 50 percent hole in a tendon. Although her mare was only 11, Henneberg made the difficult decision to not bring her back to competition.

“She’s pretty difficult when she’s in work, and she’s not happy being turned out, so she’d spent most of the last year in a stall, because I couldn’t take the risk of her being hurt before the Olympics. She wasn’t happy,” said Henneberg. “She would have had to be in her stall for a year with that injury.”

So Henneberg turned Cheapers out and ignored the mare she’d spent so much time pampering as she paced the fence and demanded to be brought back in.

“Eventually she became happy, and then she became really happy,” said Henneberg. “When you buy a horse at the age of 13 for $600 and go to the Olympics, and they give you their heart and soul—I figured she deserved to get a buddy and go out and be a horse.”

Henneberg then bred Nirvana. In 1996, she’d won a breeding to Espiritu for being the highest-placed mare at Rolex Kentucky. Just last year, Henneberg sold that horse to a student of Mike Huber. She also bred the mare to Cruising.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I kept the first one for a while, but I think I was looking to clone her, and I wasn’t doing a very good job,” she said. “They just weren’t her.”

Henneberg decided the second foal would be the last, since Nirvana had trouble delivering it and bled a lot. “I would never have been able to live with myself if something had happened to her,” she said.

Over the years, Henneberg said people have asked her again and again why she didn’t produce more foals from Nirvana. “It’s tough to explain to other people, but she’s such a difficult mare. She’s happy now, and she has a home for life. She lives in a big field with a run-in and her pals. I don’t think she deserves to have her life uprooted for my plans,” she said. “I just want her happy and content for the rest of her life. I hope to find something like her, just not out of her.”

Still Best Friends

But if you think you’ve seen the gray mare flashing around a cross-country course since then, you’re right. A student of Henneberg’s ran her at a few horse trials in 2003.

“She was a fabulous rider and came from the same background as me of a working-class family,” said Henneberg. “Those were the only events the girl had done, and the mare had a blast.”

Now, at the age of 22, Nirvana is the boss of her paddock. “She looks fabulous,” said Henneberg. “She’s fat and happy, and she’s pretty wild some days.”

Henneberg trains for Mike and Kelly Beck and their six children at Ten Oak Farm in Tallahassee, Fla., and Nirvana, of course, lives there, where Henneberg visits and grooms her every day. “She’s not a horse dying to be rubbed on for hours; I just want to make sure she sees my face,” said Henneberg. “Whatever it is that made her so tough also made her so good, and I look for that in her every day still. I want to make sure it’s still there.”

Even as she works with new prospects, not a day passes that Henneberg doesn’t think of her time with Nirvana, or thank her for making her the rider she is today. “If I had to give up every horse in the barn to keep her in the field, it would be done,” she said. “There’s not a single thing I have in my life that I can’t attribute to her.

“It takes a pretty extraordinary horse to do what she did, taking a rider who had no idea what she was doing along with her,” added Henneberg. “She had to deal with massive mistakes on my part, and she was able to forgive those mistakes.”

After Nirvana, Henneberg returned to the advanced level with another off-the-track Thoroughbred, Simon Sez. They finished 12th at the 1999 Fair Hill CCI*** (Md.), but Henneberg then sold the horse to Marcia Kulak.

“I was at a point where I was an adult and had to make a living,” she said.

And now she’s loving her job in Florida, training the Beck family and selling horses they import. “I love competing; it’s just not high on my priorities right now to ride at that level,” she said. “That doesn’t mean it won’t happen. But building this facility is a big project, going on two years, and I’m just getting settled.”

She said the Becks would support her if she decided that going back to the Olympics was a priority again. “They’d be behind me either way,” she said. “They just want it to be a fun place.”

In the meantime, Nirvana continues to play a big role in Henneberg’s life. “Having a horse like that so early in your career is a blessing, but you wonder if there’s ever going to be another,” she said. “The good parts and the bad parts [of my career with her] have shaped me as a person. She isn’t just a horse to me—she’s my best friend in the whole world.”

Would Nirvana Be Competitive Today?

Jill Henneberg acknowledged that in the decade since she competed Nirvana, dressage has become increasingly more important in eventing. But she still believes the mare would be a top competitor, because the show jumping has taken on an equally more important role.

“Show jumping is bigger now, and this is a mare who probably had six rails in her entire career,” Henneberg said. “I still think she would have been in consideration for teams, because her cross-country and show jumping were so dependable.”

And, she said, in working with Capt. Mark Phillips for two weeks before the Olympics, they managed to drop 10 points off her dressage score.

Henneberg admitted that her inexperience hampered the mare the most in the dressage. “If she’d been bought as a 3-year-old by Karen or David [O’Connor], she probably would have been fine on the flat. I’m willing to take responsibility for that,” she added with a laugh.

But she still thinks you can find a “diamond in the rough” for upper level eventing. “There are a lot of really, really nice horses who are not expensive and are every bit as talented as the ones you spend the money on,” she said. “It’s just a matter of putting in the time and effort.”

Bits About Nirvana

• The 1994 Rolex Kentucky CCI*** winner, Julie Gomena’s Treaty, shared the same sire as Nirvana. Hawkins Special, a stallion who stood in Arkansas, didn’t produce much for the track but sired two horses who made it to Rolex Kentucky.

• Before buying Nirvana, Jill Henne-berg’s riding experience was limited to weekly lessons and a half-lease on an older Quarter Horse.

• Nirvana never contested a two-star—she went straight to the three-star level after a few one-stars.

• Henneberg never considered selling her mare, despite several offers. “She had a home for life, probably from the get-go,” she said with a laugh. “There wasn’t a price tag big enough.”

Beth Rasin