On October 10, 1964, a young Japanese student named Yoshinori Sakai raced up the steps of Japan’s National Stadium, clutching the blazing Olympic torch in his hands. As a clamorous crowd of 83,000 people applauded, Sakai stopped in front of the Olympic cauldron and stood still, marveling at the immensity of the moment. He beamed, raised the flaming torch into the air, and ignited the cauldron, heralding the start of the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games.

Sakai’s role—and the Olympics themselves—had an importance that transcended sport. Sakai, 19 at the time, was born just outside of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the day on which the city was devastated by an atomic bomb. That same year, Tokyo was nearly razed to the ground by brutal firebombing. The 1964 Olympics, however, expressed Japan’s hope in a bright, peaceful future. As the torchbearer to light the Olympic cauldron, Sakai was a living symbol of the recovery and redemption that the games brought.

A Hard-Fought Silver Medal

The Olympic equestrian events started on Oct. 16, drawing riders from 20 countries. Aside from holding some of the equestrian events in Baji Koen Park—the same location in which the equestrian sports will be contested this year—Japan also provided a sprawling eventing course at Karuizawa, a forested area 90 miles from Tokyo.

Other nations were faced with the daunting task of transporting their equine athletes to Japan. The Australian horses, for instance, were herded into wither-high shipping crates and lifted by crane onto a ship, giving them a terrifying view of the ground falling away beneath them. After their ship docked in the Japanese city of Kobe, the horses still had a 360-mile cross-country journey before finally reaching their destination.

The equestrian sports kicked off with eventing, which marked a significant milestone in Olympic history. Until 1962, women were barred from competing in Olympic eventing. Almost immediately after the ban was lifted, a young equestrian named Lana DuPont launched a bid for the U.S. team. She earned a spot to Tokyo as the first—and, at the time, only—woman to compete in Olympic eventing.

When a reporter reminded her about some of the mishaps that had occurred in the sport, DuPont simply shrugged in response, said The San Francisco Examiner of Oct. 16, 1964. “It’s much more dangerous crossing the street in Tokyo,” she admitted. “Those little careening cars scare me to death.”

A member of the prominent DuPont family, Lana’s life was deeply entwined with horses. Her mother, Allaire, was the owner of Bohemia Stables, a racing operation that had produced myriad champions. At the same time as her daughter embarked on her Olympic quest, Allaire was in the midst of campaigning the brilliant Kelso, the only Thoroughbred in history to earn five consecutive Horse of the Year titles.

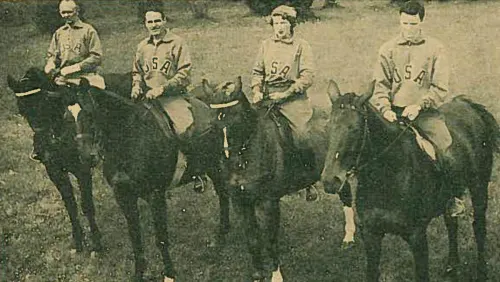

Lana was joined on the Olympic team by Michael Page, J. Michael Plumb and Kevin Freeman, and they would win a silver medal in Tokyo.

According to Page, the highest-placing member of the eventing team in fourth, the path to the team silver wasn’t easy. The cross-country test consisted of five sections: the road phase, the steeplechase, a second road section, cross-country and a final road phase. Midway through his cross-country test, Page’s horse, The Grasshopper, started to show signs of weakening.

“He was short on his gallops and in wind,” Page remembers, “and 100 yards from the end of the steeplechase, he slowed down. I thought I was going to have to pull him up.”

As Page knew very well, however, The Grasshopper was a horse of singular tenacity. Four years earlier in the Rome Olympics, Page had an experience he would never forget. After a 22-mile cross-country test in which the team sustained two falls, Page and The Grasshopper finally reached the end of the course.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I got there,” Page remembers. “There was a big, open place. We had gone 22 miles, had two falls, and I couldn’t stop him.”

The Grasshopper simply refused to stop running. As the famous U.S. pentathlon coach Colonel John Russell looked on, Page and his mount proceeded to gallop around in large circles. Russell began to yell, “Michael, you have to stop!” The Grasshopper continued to race around as Page shouted, “I can’t stop him!”

As The Grasshopper neared the end of the Tokyo steeplechase, Page decided to stay in the competition and hope for the best. Sitting nearly motionless in the saddle, Page waited to see what his mount would do. The result was astonishing.

“He [The Grasshopper] was so unique,” he recalls. “He went through the finish line, and then—for the next mile or two—he started to get stronger and stronger.”

By the time The Grasshopper reached the cross-country phase, he was running so easily that he earned the highest possible score. Page remembered his decision thus: “If I had pulled him up, I never would have gotten to the medal stand.”

Lana also encountered difficulties, as she and her horse Mr. Wister fell on the grueling course. “We fell hard, Wister breaking several bones in his jaw,” she told The Equiery in an article that ran in 2000. “We were badly shaken and disheveled, but Wister was nonetheless eager to continue.”

They continued onwards until Mr. Wister stumbled over a spread fence, falling for a second time. Despite these setbacks, the pair completed the course. “When we finished,” she recalled to the Equiery, “we were a collection of bruises, broken bones and mud. We proved that a woman could get around an Olympic cross-country course, and nobody could have said that we looked feminine at the finish.”

After her ordeal on cross- country, Lana put in a solid showing in the show jumping to become the first woman in Olympic history to complete the eventing competition. Her feat had massive implications.

“Had she not completed the course,” Page recalled, “probably women wouldn’t have been allowed to ride [in eventing].”

None of the U.S. riders medaled in the individual competition, which was won by Mauro Checcoli of Italy, whose brilliant performance on cross-country and flawless completion of the show jumping allowed him to clinch the gold medal. The Argentinian Carlos Moratorio finished a hard-fought second to earn Argentina’s only medal of the 1964 Games, defeating Germany’s Fritz Ligges for the silver. The American team came in second, beaten by the strong Italian team. With the eyes of the world upon them, the first co-ed eventing team climbed onto the podium and had silver medals—the only equestrian medals won by U.S. riders during the Tokyo Olympics—draped around their necks.

Michael Page, Lana DuPont, Michael Plumb, Kevin Freeman and coach Stefan von Visy. Carmine Petriccione Photo

Surprises

The U.S. equestrian team wasn’t nearly as successful in the other Olympic disciplines. Three days after the conclusion of eventing, 22 athletes took part in the dressage competition. The event began with a qualification round, after which the six highest-scoring riders would advance to the finals. No American finished better than eighth.

ADVERTISEMENT

After a preliminary round in which Harry Boldt, who competed for the United German States (East and West Germany competed as separate countries from 1968-1988 Olympics), dominated his competition, riders from just three nations moved on to the finals. In one of the closest contests in the games, Boldt gave a good performance but was edged out of first by the Swiss rider Henri Chammartin. The difference between their two scores was a single point.

In show jumping, Pierre Jonquères d’Oriola of France became the first jumper to win two individual gold medals, having also won in 1952.

The show jumping competition, run over a ground soaked by rains, didn’t go particularly well for the U.S. team, however. Out of 46 riders, the U.S. competitors finished seventh (Frank Chapot), 13th (Kathy Kusner) and 33rd (Mary Chapot). Kusner would go on to become the first licensed female jockey in American history and the first woman to ride in the Maryland Hunt Cup.

On the other hand, the newly formed Australian show jumping team experienced a surprising degree of success. Up until that point, the only Olympic equestrian sport in which Australia had participated was eventing. Immediately, they proved that they were a force to be reckoned with. Aboard, says Equestrian Australia’s website, a “brilliant little black gelding,” named Bonvale, John Fahey put in two sensational rounds to tie for third. This presented the presiding judges with a dilemma.

Over the course of Olympic history, no tie had occurred. The Olympic judges decided to resolve the issue with a jump-off. Fahey and Bonvale had two fences down and were beaten by British rider Peter Robeson, who put in a clear round. Nonetheless, Fahey’s performance was— and still is—the best individual jumping performance in Australian Olympic history.

The Olympic Games came to a glorious conclusion on Oct. 24. Underneath a gray, “somber,” sky, according to a report in the 1964 Kentucky Paducah Sun, the athletes paraded onto the field for a final time. One spectator, as it transpired, was not content to simply watch the proceedings. Just as the Olympians began to march onto the track, a man named Arnold Gordon—who was not an athlete—raced onto the field. Instead of immediately apprehending Gordon, however, the police simply ignored the man. In front of the astonished crowd, Gordon proceeded to run two laps around the oval in a white track suit, the number 351 flapping against his chest. Gradually, the spectators warmed up to the ebullient man and started to cheer him on. Gordon, who was obviously a natural showman, waved in response to the roars from the stadium, stopped once and pretended to conduct the band, and “pranced” off the track.

After the spectacle, the closing ceremony continued. The flagbearers marched onto the track, holding their national flags aloft. The crowd was in for one last surprise: One country held a placard that read, “Zambia.” The nation had entered the Olympic Games under the name Northern Rhodesia, while still under English influence, and declared its independence on the final day of the Games.

Finally, the floodlights that illuminated the stadium were extinguished, and the Olympic flag was lowered. During the last minutes of the ceremony, a gentle, almost misty rain began to fall.

“It sprinkled a little, as if the skies were weeping for the occasion,” one witness said to The Paducah Sun. “And there were tear drops, too, in the eyes of more than a few of the crowd of 70,000.”

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our July 19 – August 2, 2021 issue.

Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked. Or you can purchase a single issue or subscribe on a mobile device through our app The Chronicle of the Horse LLC.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.