Horse shows in the mid-20th century America were society events. The well-heeled and the famous would arrive, be seated in swanky hospitality accommodations with food and drink, and people watch, as well as horse watch. As in horse racing, the horses themselves were sometimes secondary to the spectators, but not to the competitors.

Most of the events were saddle seat, hunters and jumpers, much like today’s iconic Devon Horse Show (Pennsylvania) or the National Horse Show when it was held at Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden. Amateurs—often the owners—and professionals both competed. Affluent society’s prominent members served on the governing boards. In 1917, these wealthy show organizers met to form the Association of American Horse Shows (now U.S. Equestrian Federation), a coalition that created a common set of rules and credentialed judges.

Of course, 1917 was also the height of the Jim Crow era, the system of anti-Black racism that had taken root in the United States after Emancipation through the 13th Amendment in 1865 and the end of Reconstruction in 1877. It is difficult to overstate the broad reach of Jim Crow, which operated by law in southern states and by custom in the North and West. The system was comprised of segregation, political suppression and systemic poverty, upheld by violence. It was so pervasive that its effects in American life were barely perceptible—until a violation of its rules led to brutal violence. While wealthier white Americans distanced themselves from the mob violence that marked the period, they also upheld the system. This included maintaining segregation, a practice that did not permit Black people to behave as equals in most areas of public life.

At most horse shows, Black trainers were allowed behind the scenes in the stable but rarely under the lights in the show ring. Jim Crow—in both custom and law—operated in the equestrian world. Black equestrians were present, but usually not as riders or drivers. They were behind the scenes serving as instructors and trainers as well as grooms. Many a high-stepping champion had been brought along by Black horsemen and -women, and many white riders had been coached by Black teachers.

Boxing champion Joe Louis built a combination boxing and equestrian training center at his Spring Hill Farm in Utica, Michigan, and outfitted it with a clubhouse, riding arena and barns for horses, pigs and cattle. Photos Courtesy Of The American Saddlebred Museum

Despite the persistence of racism, Black equestrians were widespread in the early 20th century. The largest number of these were in the South, where they had generations of experience as stable workers and trainers dating back to slavery. As a result of their geographical origins, they tended to be experts in saddle seat riding, a style that had developed on southern farms and plantations. The heart of saddle horse breeding was in central Kentucky.

Distinguished by the rider’s very upright posture and the high steps and head carriage of the horse, saddle seat also carries an element of flash and swagger. At competitions, horses toured an arena at various gaits, cheered on by an appreciative audience. They were judged on the quality and brilliance of their movement.

The most famous of the Black saddle horse trainers was Tom Bass of Mexico, Missouri. Bass was born in 1859 to an enslaved mother (thus inheriting her status) and a white father, who was also Bass’ enslaver. The white Bass family bred saddle horses, and Bass’ talent was likely evident from an early age. An exception to the customary exclusion of Black riders from the show ring, Bass was internationally recognized as a horseman and was inducted into the Saddlebred Hall of Fame in 2017. He was only the most prominent among countless Black horse trainers of his era.

As the Black population of the United States shifted northward and westward throughout the 20th century, some brought their equestrian skills with them. Among those Black families wealthy enough to pay for lessons or buy horses, equestrian sport became a popular social pastime.

The Joe Louis Effect

ADVERTISEMENT

The appeal of riding and showing increased exponentially when world heavyweight champion boxer Joe Louis became a prominent rider and owner. Louis (born Joseph Louis Barrow in Alabama in 1914) began his heavyweight career in 1934 and claimed the world title in 1937. He would hold the title until 1949, but his peak years were between 1937 and 1942.

As his fame rose, so did his interest in horses. He took riding lessons from the Black trainer Shadrach Hatcher while at a training camp at the Waddy Hotel in West Baden Springs, Indiana. Louis fell in love with the sport. He bought some well-bred saddle horses and in 1938 put on a horse show for Black competitors at Bell’s Academy in Utica, Michigan. The show was in June, just after his victorious rematch with Max Schmeling. The show served a dual purpose as a homecoming event for Louis and a chance for Black equestrians to show off their horses. There were six trophies for the winners, including one that Louis himself donated, and horses, riders and owners traveled from Chicago to compete. The show was a huge success, with tickets in high demand. Not only had Louis won the match with Schmeling, but his horse McDonald’s Choice won a trotting class and the owner’s class with Louis up. His other entry, Bing Crosby, won the conformation and style and professional classes.

The Chicago guests were happy to reciprocate and held a Black horse show a few months later. The first Midwest Horse Show Classic was held in September in front of 1,700 fashionable spectators at the American Giants Park. In Chicago, Louis collaborated with several others to create what was called “one of the finest events of the season.”

It was “the first time Race exhibitors and riders of the Midwest have presented their horses, show-fashion,” said the city’s famous Black newspaper the Chicago Defender, using a popular term for those who were considered good representatives of Black people. The Defender ecstatically reported that “good sportsmanship, good fellowship and deep appreciation emanated from a mass audience enraptured from the peak of its impeccable attire to the toe of its rejoicing feet.”

The appeal of riding and showing increased exponentially when world heavyweight champion boxer Joe Louis became a prominent rider and owner.

Joe Louis’ horse Joko won a five-gaited class under a different rider, but his top horse, Flash, was just edged out of first place in the five-gaited stake class, the main event.

By the next year, Louis had decided to build a combination boxing and equestrian training center. He purchased what he called Spring Hill Farm in Utica and outfitted it with a clubhouse, riding arena and barns for horses, pigs and cattle. He hired veteran Michigan trainer Henry Jennings, married to fellow equestrian Lydia Davis Jennings, to manage the riding horses. The first show on the site was planned for October 1940, just after the third annual Chicago show (attended by Duke Ellington, among others). This time the guests could watch from box seats above the ring or from the veranda of the club house. Tickets were almost as hot a commodity as those for the Detroit Tigers’ World Series game. Ultimately, about 4,000 people showed up for the festivities.

A Pent-Up Demand

The intense popularity of the events suggests that they served a pent-up demand. Black equestrians and horse owners were determined to show that Black people were not only those who cleaned up after horses but also those who enjoyed them. Together with Louis, there were a number of prominent Black people who had acquired horses and learned to ride: Chicago businessman Iley Kelly; his daughter Loretta Sue Kelly; Montell Stewart, a Chicago businessman who had purchased a farm not far from Louis’; and physicians Alf Thomas, C. C. Whitby and Paul Alexander.

A collection of Black riding clubs had popped up across the Midwest and Northeast: the Utica Riding and Hunt Club that had put on the very first show at Bell’s Academy, plus the Detroit Equestriennes for girls 14 and under, the Frogs Golf and Riding Club in Harlem, New York, the Elite Riding Club of Indianapolis, and a host of clubs in greater Pittsburgh. There were also Black trainers and stable managers who were working for Black riders and owners: Henry Jennings for Louis; George West at his riding academy in New Jersey (his daughter Natalie West competed as well as his students); William Bell, who rode both hunters and saddle horses in Michigan; Louis’ former bodyguard William “Big” Russell; Montell Stewart’s rider James Quisenberry; and William Shannon of Chicago.

ADVERTISEMENT

These trainers, riders and owners were a ready constituency for Black horse shows. With an appreciative middle-class Black audience, they supported the competitions that were held through the early 1940s. Perhaps the biggest of the Black horse shows was the Harlem Horse Show, held in August 1941 on the former site of a Negro League ballpark in Upper Manhattan.

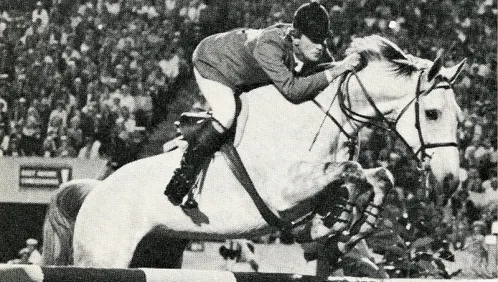

A benefit for the New York Urban League and the Hope Day Nursery, the Harlem show was “the season’s gala event for the social elite of New York City,” according to the Defender. More than 7,500 people attended, and the day raised over $3,000 for its charities. There were hunters, jumpers and saddle horses, just like the National Horse Show. The judges included Mrs. Walter Brundage, an experienced member of the National Horse Show board. Louis was represented by Henry Jennings aboard Flash, and the chestnut with chrome walked away with the five-gaited championship trophy. But the most exciting moment of the weekend was when Leslie Williams of Briar Cliff, Virginia, jumped over a car on his horse Shannon Power.

The shows continued for several years. Another event in Pittsburgh sprouted, and Flash won there too. Black soldiers on duty at the infantry school stables even put on a horse show at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1941. The peak of both Louis’ boxing career and his riding career was from 1938 to 1942, and the horse show fad in Black social circles followed the same trajectory. By 1944, Louis had enlisted and no longer had the income from regular matches to support the farm. He sold it, and it has since become part of the River Bends municipal park.

In wartime, and without Louis’ celebrity, the shows appear to have died out. The idea never re-emerged after World War II.

Though short-lived, the Black horse shows were major events that show important truths of their time. The events were not just equestrian competitions but social and cultural gatherings where Black people were both the elite and the workers. Not only were Black people able to ride, but they could do so away from hostile white gazes and the humiliations of Jim Crow.

Pride in Black achievement, celebrity watching, and exciting entertainment made the eagerly anticipated festivities the place to be, without the racism that pushed Black people out of most such events. The fact that the events were sometimes benefits for organizations that promoted civil rights and services made them even more attractive. They show that the story of Black Americans’ equestrian interests is long and suggest that a new chapter of diverse participation in horse sports is possible.

The American Saddlebred Horse Museum provided much information for this article. For more stories of Black equestrians, visit the Chronicle of African Americans in the Horse Industry at africanamericanhorsestories.org.

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our May 17-31, 2021, issue.

Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked. Or you can purchase a single issue or subscribe on a mobile device through our app The Chronicle of the Horse LLC.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.