In the early afternoon on Feb. 11, 2022, Katharine Chrisley-Schreiber, founder of Dharmahorse Equine Sanctuary in Las Cruces, New Mexico, heard her husband, Mark Schreiber, utter three words she had hoped she would never hear again: “There’s a fire.” Earlier that day, a brush fire started in a community some distance north of them, but blustery winds and exceedingly dry conditions in their high desert region meant the blaze was heading their way, and quickly. They could already see thick black smoke on the horizon.

Immediately, the couple sprang into action. Katharine soaked their two barns with a hose, then they grabbed halters from a well-organized rack and moved all of their equines from the track system that lines the edge of their property into a centrally located round yard. This area, made of pipe panel fencing and purposefully kept free of flammable material, provided a secure and relatively fire-proof place for the animals to stay while the blaze was extinguished. By the time wind-blown embers began melting through the electrical tape on the track system, the entire herd was safely relocated, and the doused buildings did not ignite—meaning Katharine and Mark could concentrate on putting out flames elsewhere.

“It was just the two of us there that day, and it went like clockwork,” said Katharine. “We knew which horses were the leaders, the horses the others would follow. Once we had everybody in the round yard, we could start pouring water in the bucket of our big tractor and dumping it on the fires burning on our fences.”

Katharine knew firsthand that without a plan, the outcome that day could have been different. Decades ago, she ran a riding school in northern New Mexico where she cared for 14 horses housed in a traditional wooden barn. One day, a large brush fire that had already blazed through three counties began to approach the property, and Katharine had no choice other than to set the horses loose and hope for the best. Fortunately, all of the animals, including a mare and foal, survived—but she knew they had been extremely lucky. When Katharine had the opportunity to design her new sanctuary from scratch, she did so with disaster-planning in mind.

“It was one of my more terrifying experiences,” Katharine said of surviving the previous fire. “But because I’d been through that, when we were planning here, everything I could think of, we tried to cover and be aware of. Because there is nothing more frightening than not being able to keep your horses safe. We’ve written it up in our evacuation and emergency plan.”

For many equine managers, emergency preparedness planning can feel like a daunting project. Emergencies often develop quickly, and when you have no plan at all, a safe outcome becomes much more difficult.

“When we are in an emergency, we don’t rise to the occasion; we fall down to the level of our preparation, and that is especially true when animals are involved,” explained Bettyann Cernese, a Pepperell, Massachusetts-based certified Equi-First Aid USA instructor who teaches courses on equine facility disaster planning across the country. “We need to have some level of preparedness, because disasters don’t send a warning.”

But there are resources available to help facility managers and owners craft plans uniquely suited to their needs. While we can’t predict every eventuality, knowing the type of incidents most common in your area, identifying and acquiring the necessary resources, and practicing in advance can all help you safely weather the worst of storms.

Know Your Opponent

The first step in creating an emergency preparedness plan is to determine the top three natural disasters or other incidents most likely to affect your area.

From there, evaluate the topography and logistics of your property to identify how these types of events are likely to affect you, and make a list of what would need to happen to mitigate those variables. Are you located in a floodplain on the Gulf Coast that will most likely require evacuation in a hurricane? Are you in a region that frequently experiences high winds, meaning that buildings and equipment storage need to be rated accordingly? Are you in an area that receives heavy snow, and need to plan for clearing loads off roofs in the winter? The types of hazards most often seen in your region will dictate the type of response you need to be prepared to launch.

“We hear about all these disasters happening all over the world, and it’s overwhelming,” said Cernese. “We focus on helping people pick the things most likely to happen. Tailoring the plan to local risk is essential. A barn in California should be preparing for wildfire, and one in Vermont for blizzards and flooding. It’s not a one-size-fits-all situation.”

But planning for the most common natural disasters in your area will also set you up to respond to unique or unusual events that may impact your facility, such as a lightning strike, a barn fire or a lost horse. Traci Hanson is the equine program director for the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries, an Arizona-based group that offers certification to organizations around the world caring for equine and other barn animals or wildlife species. All GFAS programs must complete a disaster preparedness plan as part of their certification process, and in doing so, members become ready to handle anything from an escaped animal to a human health emergency to civic unrest.

“We focus mostly on natural disasters, like wildfires or floods, but a lot of the steps taken to prepare for these incidents can apply to other disasters,” said Hanson. “It is about trying to get groups to think ahead, plan ahead, and think about what they can do to get ready.”

When Disaster Strikes

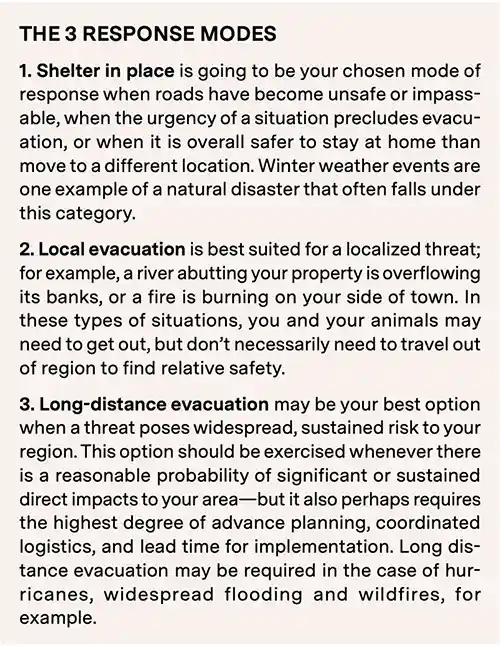

When it comes to navigating a natural disaster, experts share that your emergency preparedness plan needs to be flexible and able to address three different response modes: shelter in place, local evacuation, and long-distance evacuation (see sidebar). Each option comes with its own considerations and planning requirements.

Making the decision to shelter in place is contingent on there being a safe location on the property for human personnel to ride out whatever is occurring, as well as space to store sufficient resources (such as feed, medical supplies and water) to get through a minimum of seven to 10 days. Among these resources, accessing water can quickly become the most critical.

“If you lose power, how will you get water?” said Hanson. “Is there a generator available, or are there ways to collect water prior to the event? We don’t require our groups to have a generator, but we do require they have an alternative, whether that is a cistern or permanent or mobile holding tank.”

ADVERTISEMENT

When a significant weather event is bearing down on your region, deliveries may be delayed or suspended, making it impossible to stock up on your horses’ essentials. Hanson notes that it is best practice to not let consumable supplies, such as feed, run too low before ordering more.

“Don’t wait until your inventory is nearly depleted,” Hanson said. “Say you know 10 bales of hay gets you through five days. Re-order when you get down to five bales, so you have that on hand in case of emergency.”

If you choose to shelter in place, communicate that decision with others—both in your local area, and further afield.

During emergency conditions, internet and phone services are often impacted, and it may not be possible to call for help if conditions deteriorate. Pre-planned emergency contacts who will know that you are still on site can reach out to rescue teams on your behalf for a welfare check if communication is lost.

When it comes to coordinating a successful evacuation—whether local or long distance—pre-identifying critical resources, including both equipment and personnel, is essential. In most cases, you will need access to trailers and pre-arranged locations set up to receive your animals, as well as familiarity with several routes to get there. Tow equipment and trailers must be kept tuned up, gassed up, and should be hitched and loaded with supplies even before the final decision to evacuate is made. Know who you will call to drive a second rig, or who can come to your farm to help you load up.

“You need contingencies for road closures and power loss,” said Cernese. “How many animals do you have, and how much trailer space do you have? If you leave to take some out because you don’t have enough trailer space, how are you going to get back if the roads are closed?”

If you are going to evacuate, you need quick and easy access to each horse’s medical paperwork, including Coggins test and vaccination records, as well as registration papers (if relevant), which can aid in identification. Experts recommend storing these items in paper form in both your tow vehicle and trailer, as well as saving them digitally.

If you are not sure where to start in terms of finding shelters set up to receive large animals in your region, consider contacting your local fire department, veterinary clinics, agricultural extension offices and large-animal savvy neighbors. Further, don’t be afraid to tap into your extended network to locate the resources you need. When designing the Dharmahorse Equine Sanctuary emergency preparedness plan, Katharine invited the local fire marshal for an on-site visit to discuss specific liabilities.

“We talked about storage of flammable materials, wiring in buildings, even what the different color of the fire hydrants meant in terms of the amount of water that comes out of them and which water system they belonged to,” said Katharine. “We talked not just about what to do if a fire comes to you, but how to make it so a fire doesn’t start at your place. He was a great help to me.”

“Even if you are a single barn owner, you need to be connected to facilities in other locations,” noted Cernese. “And if you are a large facility, you still may need to connect with the wider farming community to have assistance with your animals.”

“Every group we work with is a different size, has a different number of horses, and may have different resources available to them,” added Hanson. “For example, maybe they have a donor with land on the other side of town available to shelter horses. But one of your resources could be a neighbor down the road, who has certain equipment and is willing to make it available.”

Regardless of which mode of emergency response you choose, it is smart to individually identify your animals in some manner for the duration of the event. Microchips provide one permanent option, but experts recommend also having a more visible form of identification available for immediate use. Livestock markers, made of a non-toxic, waxy material, often in a bright neon color, can be used to write a phone number on each horse. Some people braid ID tags containing the owner’s contact info into their horses’ manes and tails. Digitally store recent photos of each animal, noting any unique markings, scars, or brands, to assist in proving ownership.

One final, but often overlooked, step is to develop a relationship with your local or state level animal rescue or response team. These groups can have different names depending on where you are located, but should pop up on an internet search. Often, they will have tools available to help you create a plan specific to your region and can help you to identify relevant resources.

Further, when a coordinated emergency response from governmental agencies is required, there is a specific protocol for the deployment of official resources that must occur. If you have a previous relationship with your local or state-level animal rescue team—and they know where you are located, and the number and type of animals you care for—they will be better positioned to get you the timely help you need as part of that coordinated response.

“The key is to not wait until disaster strikes to connect with those people and organizations,” said Cernese.

Practice Makes Perfect

The best written and thought-out plan will do no good if those responsible for executing it are not intimately familiar with each of the steps involved. Not only should your plan be publicly posted and shared with key players—including local emergency responders—experts recommend holding practice drills at least once, if not twice, a year, inviting anyone and everyone who might be called on in an emergency.

“If you have a big facility, and you’re not always there, do the people that are going to be there know your plan?” said Cernese. “Train all the people you possibly can. Do a walk through [to identify] what is working and what is not.”

ADVERTISEMENT

There are several ways to practice putting your plan into action. Most models involve creating an imaginary scenario, with participants role-playing their response to each variable presented.

This can be done at the facility itself and using the actual equipment available, or as a “tabletop” exercise, using a large map of the facility on which people can point to where resources are located. Often, these drills highlight areas where improvement is needed, and they give planners the opportunity to make corrections, large and small.

“You can act the scenario out as if people are in their actual roles, or you can switch it up, which offers a new or different perspective,” said Hanson. “Another good way to practice is to remove a key person—maybe your barn manager, or executive director—the people everybody goes to for everything. Because if your barn manager is on vacation, and there is an emergency—what are you going to do?”

One excellent way to identify your plan’s weaknesses is to hold an unannounced practice. Instead of proceeding through your facility’s typical routine that day, a mock emergency is announced, and whoever is present is forced to put the emergency preparedness plan into action.

“Yes, it messes up that day, but it is imperative for your team to know, not just in words, what they need to do,” said Hanson. “When you’re acting it out, that’s where you’re going to find the things you didn’t think of. It’s not going to work exactly as you planned—so how do you tweak it? Who are your strong people, and do we need to reallocate those roles? It’s quite telling.”

“Having an emergency plan is not just about the equipment; it’s about being able to make calm decisions under pressure.”

Bettyann Cernese

When she facilitates a mock drill, Cernese sees a range of instinctive responses from participants, even when no actual emergency is occurring.

“We kind of do fight, flight, or freeze responses, or slow processing,” said Cernese. “Some people panic a bit. It really highlights why having situational awareness and emotional regulation is almost as important has having that plan on paper.

“Having an emergency plan is not just about the equipment; it’s about being able to make calm decisions under pressure,” she continued. “Our ability to regulate our own nervous system is one of the most important tools you can bring into a high-stress emergency with horses.”

If evacuation is part of your plan, one additional area of practice is to work with your horses enough that they will load reliably, under stressful conditions, even for someone they may not know. Familiarize your animals with being approached quickly as well as under unusual situations, such as after dark. Be sure to have plenty of appropriately sized halters and spare lead ropes available, at every entrance or exit to your facility.

Plan, Not Paranoia

After their experience with brush fire in 2022, the team at Dharmahorse made a few revisions to their emergency plan.

First, they added more gates to their round yard, so that it was more quickly accessible from anywhere on the property.

Secondly, they prioritized fundraising for a project that was already on their wish list: installing a water line with frost-free spigots around the entire facility.

“It will make you paranoid if you let it, thinking about all the things that can go wrong, but when we had that fire, we knew how to get the horses safe,” said Katharine. “For me, I would rather plan and not need it, than need it and not have planned. Knowing that we’ve been through this before, and it worked, makes me much more relaxed. It kept everybody safe, and it keeps you from panicking in the moment.”

Having a plan—and practicing that plan—can help give equine managers the confidence they need to make the best choices in an emergency, quickly.

“Hope is not a strategy: ‘I hope it never happens to me,’ ” said Cernese. “Having a plan in place isn’t about paranoia; it’s about protecting the lives of the horses we’re responsible for.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2025 issue of The Chronicle of the Horse. You can subscribe and get online access to a digital version and then enjoy a year of The Chronicle of the Horse. If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.