Girl horse meets boy horse. Girl horse falls in love with boy horse. Girl horse and boy horse make a baby.

OK. So I knew it wasn’t going to be that easy. For one, Cairo will likely never meet her baby daddy. This isn’t “Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron” or some Disney movie. This is Queen Of Cairo, sassy mare of Oregon, and the free-cooled semen of Gemstone Clover, FedExed to us from Colorado.

And this is Cairo. To paraphrase my vet, Dr. Wes Violet, she’s a project.

I’ve said it before: The only thing that comes easy for Cairo is jumping. For Cairo and I to get to prelim together, when she was fairly green and I’d never gone past training level, speaks to how good she was at that. She’s also really, really good at coming into heat. My veterinarian gently pointed out that, when it comes to getting pregnant, at some point she needed to stop coming into heat.

Dr. Wes is amazing. There’s a reason there are a lot of fillies running around Oregon’s Willamette Valley named Violet after him. And Gemstone Clover is as fecund as they come. (Dr. Wes let me check out his enthusiastic swimmers under the microscope, so I can attest that they are frisky.) And his owner was supportive and offered advice. Colorado State collected and shipped the semen like the pros they are.

Cairo, however, was not easy.

Hindsight is 20/20—or in my case, 2020. Had I bred Cairo in 2019, as I pondered doing when she injured her hind high suspensory the first time, she would have been younger. Perhaps she would have had a 2020 baby, and either way, I would have not had a show season, thanks to your good friend and mine, COVID-19.

But I was operating on the idea I could rehab her and return to competition that next season. Like many things in 2020, that didn’t really work out.

So in 2022, I wrote about my choice to breed and how I was pushing the go button. And I plead guilty to not ever updating anyone very much after I pressed that button, to the degree that I even annoyed my friends with my lack of updates.

Cairo took on the first breeding that spring. But she developed an infection, a common problem in older maiden mares. We cultured the infection and treated it with antibiotics but, as Dr. Wes said, an infection is not conducive to the survival of an embryo.

So we started over and tried again. Cairo took on that try, and I celebrated. But that little embryo didn’t grow.

I started update after update—either for the Chronicle or even just for my friends who know how much this means to me. But I kept stopping. My heart was hurting. How, I wondered, do women deal with infertility when I was devastated over a horse was not staying pregnant?

We threw the book at Cairo. My vet, who loves doing fertility work, consulted other experts: platelet poor plasma, uterine cultures, lavages, we did all the things.

Suddenly I understood why my sister didn’t tell anyone when she was pregnant with her much longed for late-life baby until she was five months along. It’s hard enough on the emotions—the appointments, the late nights and early mornings, but then you also have to deal with other well-meaning people’s opinions and emotions.

There were the folks who kept asking if she was pregnant when I just didn’t know, and I was fretting over more infections. “Did you know you were pregnant one week after having sex?” I asked one of them. Others offered comments like, “Maybe she doesn’t want a baby,” or “Maybe it’s not meant to be,” or my personal favorite, “Maybe you shouldn’t have talked about it.”

So I stopped talking about it.

The summer went on. I watched other people ride and jump and compete the way I wanted to, and we treated another infection, and we tried again. Cairo didn’t take. I was done. Financially, emotionally, everything. The only bright spot was that the prednisolone we had given Cairo to quiet her unruly uterus had also quieted her lameness. We injected platelet-rich plasma in her coffin joint, and she was sound. But not pregnant.

I was at the vet clinic so much I began to think of one of the spots behind the barn where I would drop my trailer as my personal parking spot, and I’m pretty sure the vet techs did too.

ADVERTISEMENT

After four tries, we still had nothing.

I sought distraction, training projects, trail rides. I started coaching Intercollegiate Horse Show Association riders for the University of Oregon Equestrian Team; they helped me with my training projects and distracted me from my sadness.

But I grieved my lost dreams. My dreams of Cairo and I doing FEI. My dreams of a baby with Cairo’s jump and maybe a little less of her buck and squeal.

Cairo isn’t going to return to competition, and I’m not ready to give up my dreams for, if not her, then her offspring. So I decided I would give it two more tries this year.

We did all the things we hadn’t already done: a uterine biopsy—hers was assessed a IIB, one step away from the worst grade of III—a Caslick’s to seal her vulva, a course of antibiotics. Then we rested her uterus for the winter. When we checked back in the spring, she still had fluid in it.

So we did the Hail Mary: Upon the advice of a fertility specialist, my vet infused Cairo’s uterus with kerosene.

Yeah, so that’s a thing.

I had heard of it. Cairo’s own breeder had it done on a mare who’d had a bunch of embryo transfers, which affect the uterus over time. I read up on it to try to understand it. There are various theories as to why it works, but the gist I got was that it regenerates the mucous membranes lining the uterus. One study showed that “[b]iopsy grades increased III to I after treatment. Nine out of 11 mated Grade III mares conceived and five carried pregnancies to term.”

My first thought was, “I bet it was a male vet who came up with this idea.”

And after I was told that mares generally don’t show signs of pain with the treatment, my second thought was, “I bet like they say the same thing about women with cramps.”

The day we did it, I asked Dr. Wes, “Where are we getting the kerosene from?”

The answer: Tractor Supply.

“There’s not, like, medical-grade kerosene?” I asked. He showed me the container he had Sharpied with the words “Cairo’s Rocket Fuel.”

No.

I held Cairo in the stocks while he and Rhonda, the vet tech, did the kerosene. They were gloved up and super careful, using a syringe and tubing and not letting it touch any exterior tissues—or themselves.

Cairo at this point was like the epitome of a bad date when she showed up at the vet’s. She demanded snacks upon arrival and promptly got wasted—she would reach her head up for a treat and expose her jugular, allow the injection and then stomp over to the stocks and kinda of pass out. “We got her needle broke,” Rhonda noted.

Needle broke yes, because she’s not the kind of mare you trusted to palpate unless she was in fact a little wasted.

Cairo showed no distress at the kerosene. We smeared her hind end liberally with zinc oxide to protect her. She showed no discomfort later that night—not that I hovered for hours or anything like that. And early the next morning, the only indication I could see anything had happened was the globs of yellow stuff that came out of her. And the fact she smelled like an arsonist if you got anywhere near her back end. She was napping in her paddock when I arrived and only got to her feet to see if I came bearing peppermints.

We lavaged her the next day, and Dr. Wes was delighted by how non-irritated how her cervical tissues were looking.

ADVERTISEMENT

We bred her on April 27, which was the next heat cycle. She ovulated on time. And she took. And I felt hopeful.

But she’s Cairo, and she’s extra, so two weeks later when we checked her, she had twinned. With twins vets typically pinch, or reduce, the smaller twin or the one easier to get to. Of course Cairo’s twins were the exact same size and practically on top of one another.

We tried that day to reduce one and didn’t get it. I was torn between the excitement that she had conceived, without fluid or infection, and the worry about the twins. Of the few people I told what was happening, I had to explain to the non-horsey ones why twins were bad (fewer than 9% of twins are carried to term, and for those the survival rate is not great). To the horsey ones I finally had to say that “Tell Wes not to pinch the good one” was only funny the first time I heard it.

When all this started I had actually thought I would care if Cairo had a colt or filly or whether it turned gray or not. By now, I figure getting a chestnut filly that will turn gray and require endless baths sounds fabulous.

I came back the next day. We were at 15 days and had limited time before the vesicles implanted in the uterus. And Dr. Wes was determined.

The vesicles were still merrily camped out on top of one another. As he palpated he began to gloomily run though the problems with having the two embryonic vesicles so close—starting with both could be lost while trying to crush one—and then my options: try again, take her to a specialist two hours away who might also fail, hope one twin eventually absorbed, or start over (hard no on that last one).

To pinch a twin, the vet needs to manually crush one of the teeny-tiny embryonic vesicles that is free floating in the uterus—without damaging the other as well—using his hands and the ultrasound probe that he’s inserted through the rectum and is using to spot the vesicles. When Dr. Wes was able to do it, he lit up.

When Cairo and I got back to the barn, with me celebrating and her hungry, I had one too many people express dismay that she wouldn’t have both babies. I again explained the risks of twins even if they do make it to term and decided to celebrate quietly on my own.

A couple days later we checked again to make sure the remaining twin survived, and I found out why people gasp with relief. I was holding Cairo’s head and my own breath while we ultrasounded. The little vesicle was there, and I breathed so loudly I almost woke Cairo up.

Then two weeks later, we did a heartbeat check, which is typically done around 26 to 30 days. My own heart was again in my mouth.

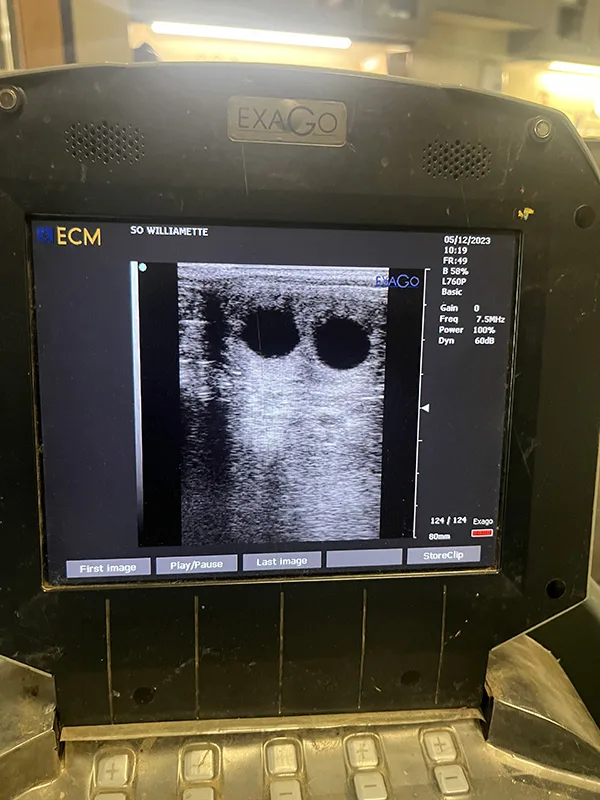

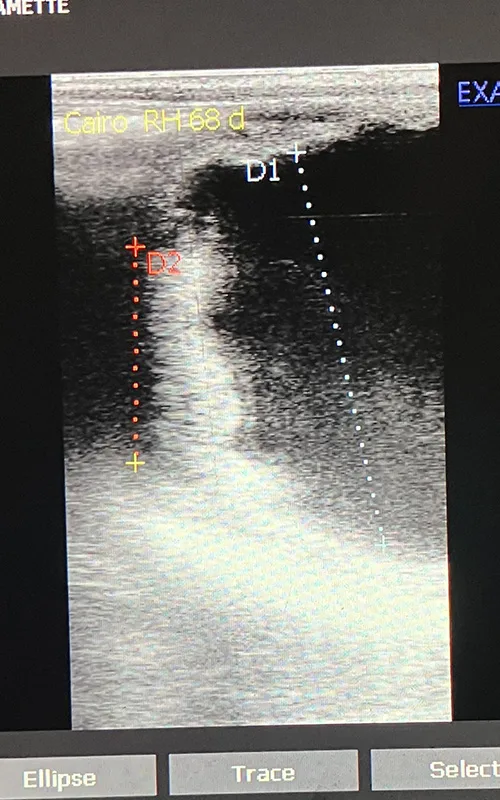

But there it was, a little flickering light on the ultrasound. I told a couple friends who had supported me throughout the crazy and began to hope.

Cairo, always hungry, has historically turned up her nose at any treat that wasn’t a carrot, apple or a peppermint. For a hangry mare, she’s always been choosy. And after she conceived, one of the things folks asked was if she was “acting different.” She really wasn’t. She’s always been a funny creature who cuddles the folks she lets into her circle of trust and tells strangers they can stay 6 feet away. Unless they have a carrot.

Sometime after we bred her, she had started to beg for all sorts of treats. To date she has snacked on Fruit Loops, gummy sour Nerds, mango licorice and at least one Oreo. Mommy munchies? Is that a thing with horses?

I don’t know, but I promise to try to keep the snacks healthy because as of right now, Cairo is now 90 days pregnant. (Irony duly noted that I’m worried about healthy snacks after we shot kerosene up her lady bits to get her pregnant.)

I’m still scared to say it. I’m hesitant to type it. But when we checked at 60 days there was a little blurry seahorse on the ultrasound screen. We’re past the stage for early embryonic loss, and Cairo has a fetus somewhere between the size of a hamster and a chipmunk.

With at least 240 days left to go, Cairo has a “baby on board” sign on her stall, and I’ve got optimism in my heart. Thank you, friends, for your patience with my silence. I’m starting to dream again.

Camilla Mortensen is an amateur eventer from Eugene, Oregon, who started blogging for the Chronicle when she made the trek to compete in the novice three-day at Rebecca Farm in Montana. She works as a newspaper editor by day.