If my mother could have chosen any hobby for her daughter, she wouldn’t have picked horses. She’d have much preferred it had I immersed myself in ballet, or softball, or music, or … anything, really, that didn’t involve a stinky thousand-pound animal around whom she has always felt rather uncomfortable. But alas, a horse kid is what she got. Over the decades, she found ways to embrace her daughter’s love in ways that worked for her, and for that, this daughter is forever grateful.

Before I was born, my mother taught high school home economics. She spent her days showing her students how to sew pillows, whip eggs and do laundry without turning their socks pink. And she stayed at school past the final bell because she also coached the high school cheerleading team.

When I came around, followed 2.5 years later by my brother, Mom transitioned to a job even more underappreciated and undervalued than teaching: She stayed home to raise her kids, toting us in the family station wagon from toddler tumbling classes to library story times to trips to the zoo or museums in town.

She curated our daily activities: finger painting for sensory play; nature walks for fresh air and exercise; a structured evening routine of bath, books and bed. She sewed my cousin and me matching dresses. She fed our fish when we forgot. She volunteered at school.

And during the limited time we were in front of a screen—an episode of Sesame Street followed by Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood in the late afternoon—she’d wipe up the day’s messes and cook dinner for the family, hot and on the table when my dad walked in the door from work. She prided herself on caring for her family, and she kept a lovely home.

But my mom had a twin and her twin had a horse. And from the time Aunt Jo lifted me up onto the back of her big, gray mare, that was it. I dropped dance by age 4, then tried some ball sports but neither the skill nor the interest was there. I skied with my family in the winter, and I learned to play the clarinet, but all I really wanted to do was ride.

In fifth grade my family moved to a house with a little stable close by and I started weekly lessons. Mom would drop me off in the barn’s gravel drive and pick me up at the same spot an hour later, a level of involvement with which she was rather comfortable, and a level of disconnect that she would have preferred to keep.

While she shared so much with her identical twin, when their embryo divided in my grandmother’s womb, all of the horse bug went to Aunt Jo. Mom didn’t even like horses, nor was she comfortable around them; they were big, they were hairy, they stunk, they could trample her if they so chose. When we visited Aunt Jo, Mom never came along when I dragged my aunt to the barn.

By sixth grade, lessons at that little stable turned into a monthly lease of a pony named P.J. As part of that lease, once a week it was my job to lead all six horses from their little paddock into the barn and feed them dinner. Because I was only 11 and maybe 70 pounds sopping wet, and because this was a job that took no more than a half hour, Mom drove me to the barn and waited on the sidelines.

ADVERTISEMENT

P.J. was a saint, but his stablemates weren’t so holy. One day, Turbo, a big, gray Thoroughbred, refused to enter the barn, planting his feet just inside the barn door. I begged and bribed that big gelding to just take a dozen more steps into his stall, but he refused to budge. I was infuriated by his stubbornness, but my mother, she’d tell me later, felt both terrified and helpless as she watched her scrawny little preteen arguing with a thousand-pound animal at the end of a rope, with absolutely no idea how to help.

After maybe 10 minutes, I asked her to use the barn’s phone to call Mr. Marsh, my riding instructor’s father, who lived just up the road and was our emergency contact during the week. Apparently, he told my mother that “he’d grab a chain and be right down,” and Mom panicked, imagining the abuse with a chain that her little daughter was going to witness if that horse didn’t get in the stall right now. And as horses do, just before Mr. Marsh arrived carrying a lead rope with a chain, Turbo had decided that he was, in fact, ready for dinner and had taken himself to his stall.

This was, I believe, only the first of many anxiety-inducing events involving my poor mother, and her horse-crazy daughter.

About a year later, with less than 24 hours’ notice, my pony was taken away when my instructor—his owner—moved hours away. Devastated, I sobbed myself to sleep for nights on end. Helpless over horses yet again, Mom sat on the edge of my bed each one of those nights, rubbing my back and questioning whether to let me keep riding, should I even want to.

When I limped from my grief and asked to find a new barn, Mom supported it, albeit hesitantly. This new barn, also nearby, was a show barn, and Mom was promoted to Horse Show Mom. For the next dozen years, from middle school through college, she struggled to understand what on earth was happening in that arena, and why on earth her daughter loved doing whatever it was. Though she stood at the rail for over a decade, she still couldn’t identify a wrong diagonal or an incorrect lead—or why those silly things mattered in the first place. She couldn’t tell a good ride from a mediocre one, and she couldn’t understand what on earth we could possibly be enjoying as we trotted in circles, kicking up dust, on hot, sticky summer days when she’d much prefer to be poolside with a book.

But despite thinking that all of us had a few loose screws, Mom came to every show. And far away from the horses, she found her own horse show niche.

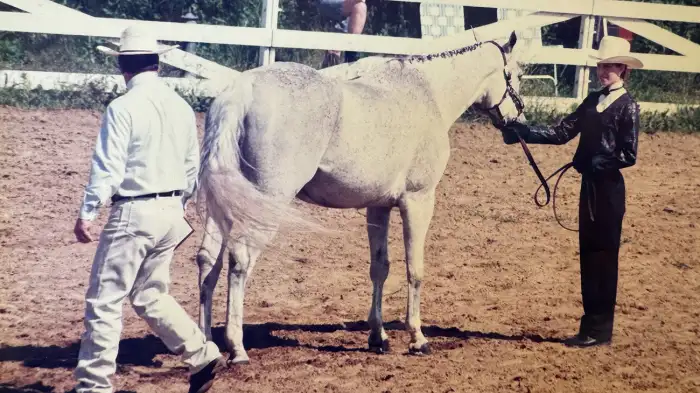

We mostly attended local shows where, desperate to rack up points for year-end awards, my barnmates and I competed in both English and Western events. Often, classes were back-to-back, and we’d change our clothes quickly in the dark, musty restroom near the in-gate while our trainer and more horse-savvy parents swapped saddles and bridles on our mounts.

Mom preferred stinky-bathroom-costume-change duty to anything that involved a horse, so she’d organize show clothing into piles, handing out ratcatchers and hunt coats and collecting piles of suede chaps and cowboy hats.

Noticing my friends and I struggling with the row of tiny buttons on our show shirts, she had an idea: before the next show, she sewed Velcro strips beneath the plackets of our shirts so we could rip them off, Hulk-style, before sticking ourselves into our next top.

She balked at the prices of Western show clothing, insisting that she could make the same vests and jackets for a quarter of the cost. We visited nearby fabric stores, scouring the drapery and upholstery sections for show-ring worthy prints. She sewed vests and jackets that rivaled anything at the local tack shop with the added bonus of truly being one-of-a-kind. Then she experimented with ultra-suede, making me a pair of teal chaps and a matching show shirt. Most of my barnmates ended up with something for the show ring made by my mother, including my friend Julie and her son Zach, whose darling matching vests were the talk of the leadline class all season.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mom also took on the responsibility of making sure that we were all well-fed during those long days. The back of our green minivan was always stuffed with homemade coffee cakes, bowls of fruit, and coolers of cold drinks, and Mom made the rounds between classes, feeding riders and their parents alike.

During my freshman year at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, a hallmate and I founded the school’s equestrian team, my first experience in the hunter world. Our team—three girls that first year—began competing as sophomores, and when shows were close enough for my parents to make the drive there and back in a day, Mom was a regular at the rail.

That is, unless I was jumping. It made her nervous, and though she’d hang around the show all day, with enough food to feed an army, and though she’d cluelessly watch our flat classes, when it came time for me to ride my course, she’d walk from the rail. Good luck, she’d say. Let her know when it was done.

When I was a junior in college, I qualified for the Intercollegiate Horse Show Association National Championship Horse Show (in a flat class, thankfully, so she’d actually stay to watch). Mom sewed a banner in my college’s colors that read “Allegheny College Equestrian Team” and proudly hung it from her spot in the bleachers. She cheered when I was awarded a fifth-place ribbon, having no idea what I’d done, good or bad, to earn that placing. She was happy, I realized, just to see her daughter doing something she loved.

Seven years ago, my husband and I bought a farm. That first summer, I hosted a horse camp for a dozen or so local, horse-crazy kids. Mom, ever supportive, appointed herself Craft Lady, planned a week’s worth of adorable horse-themed crafts: fleece pillows and pool-noodle horses and hand-printed t-shirts and glittery horseshoes. She took over the tack room, kicked out the barn cats (“They’re putting their dirty paws on my craft tables!”), and helped campers create.

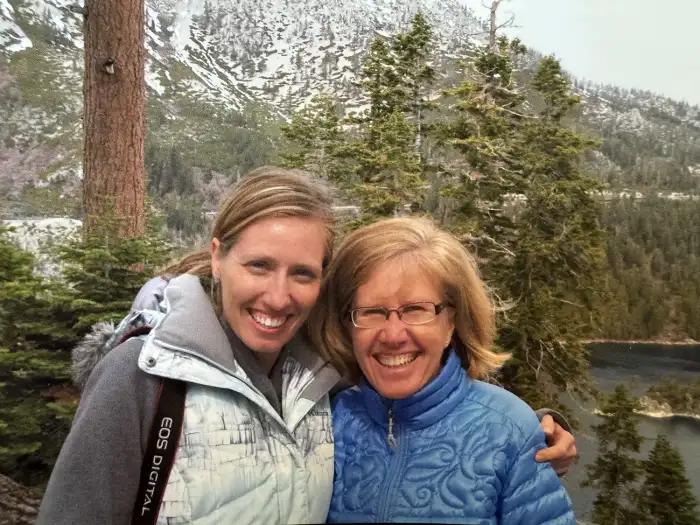

She’s not going to lead a horse in from the field. She’s not going to wield a brush or buckle a bridle. She probably can’t tell you the names of more than one or two of her dozen hooved grandchildren. But she can tell you that horses—though she can’t understand it—are the great love of her daughter’s life.

And over the course of more than three decades in horses, I have come to realize that not a single one of my horse dreams could have come true without the support of my mother.

If you have a mom who loves horses, you’re lucky—what a gift to share something so special. But if you are like me, with a non-horsey mom who has supported your horse-crazy dreams while thinking they’re bit nuts, I’d argue that we’re even luckier. It’s easy, I imagine, for parents to support an interest that they share with a child. It’s far more challenging, I’d imagine, for parents to support a hobby that they don’t understand, or that makes them so nervous that they can’t even stay at the rail to watch.

So happy Mother’s Day to all the moms, the horse-crazy ones, and the ones who think we’re a little crazy for loving horses ourselves!

Sarah K. Susa is the owner of Black Dog Stables just north of Pittsburgh, where she resides with her husband and young son. She has a B.A. in English and Creative Writing from Allegheny College and an M.Ed. from The University of Pennsylvania. She teaches high school English full-time, teaches riding lessons and facilitates educational programs at Black Dog Stables, and has no idea what you mean by the concept of free time.